The making of: Chord Mojo

A portable DAC that lives up to its Mojo (‘Mobile Joy’) name

The latest hi-fi, home cinema and tech news, reviews, buying advice and deals, direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Sometimes it’s the little things in life that give us most pleasure. Freshly washed sheets, the day’s first rays of sunshine, a perfectly baked cupcake. Or, to take that idiom more literally, a wedding ring, a child’s first tooth... or even a pocket-sized device that makes your computer or smartphone sound miles better, like the Chord Mojo.

After over two decades of making high-end DAC separates (among other hi-fi components), Chord first flirted with portability with the rechargeable Hugo in 2014. A year later, the Mojo opened the company’s doors into mobile - an area where digital-to-analogue converters were beginning to truly flourish. And it unquestionably lived up to its Mojo (‘Mobile Joy’) name.

The £400 Mojo is the bottom bun in the company’s five-layer DAC sandwich (the £8500 DAVE being Chord's sesame-seeded topper) and among the more recent products in Chord’s 29-year history - which seems relatively short given the age of the renovated pump house in Maidstone (pictured below) the company and its 30-odd employees call home.

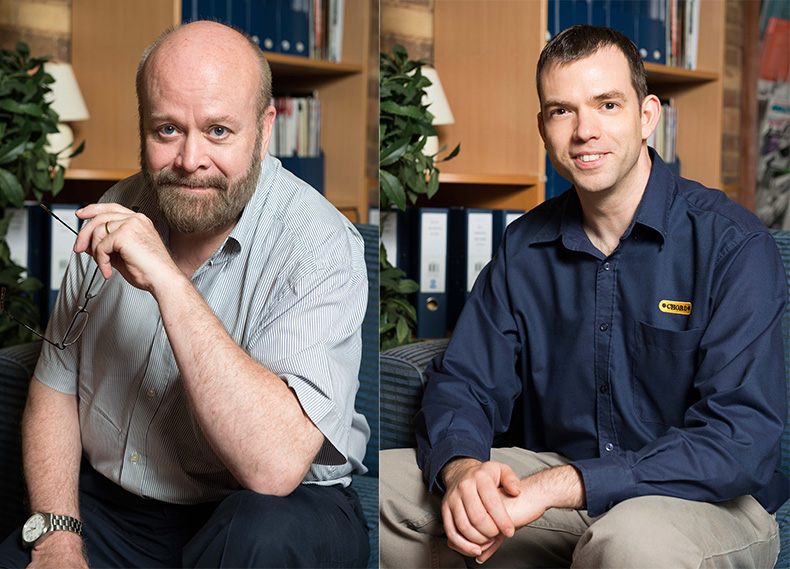

In their top floor showroom, we sit down with Chord’s John Franks, Managing Director and Chief Designer, and Matt Bartlett, Production Director and designer, to talk everything Mojo - from Chord’s FPGA (Field Programmable Gate Array) DAC technology, to societal change affecting hi-fi ownership, to why MQA is a no-go for the brand.

MORE: DACs: everything you need to know

The path to portable

Like most good success stories, the Mojo’s began several years before it came into being. And it almost justifies the Disneyfied ‘once upon a time, in a land far, far away...’ introduction.

“We tried smaller products in the past", says John. "Years and years ago, we had a product range called Chordette, which we happened to sell a vast number of to a global tech leader. That was good for us, and having done that we suddenly realized that boutique hi-fi was probably going to grow.

The latest hi-fi, home cinema and tech news, reviews, buying advice and deals, direct to your inbox.

“There were several things that were causing the growth. In demographic terms, people of my generation would have dated in their teens and early 20s, then married, bought a house, got their car, bed, TV and hi-fi. Hi-fi was fairly high up on their list.

“That doesn’t happen now. People don’t get married in Korea until they’re nearly 40. It’s the same in Italy. It’s happening over the world. People have these extended adolescences where they don’t have their own large space, just, say, a room with a desk with a PC on it. Making vast amounts of hi-fi was not the way to go. We needed to get to those desktops.

“I went to a Head-Fi show in Tokyo about seven years ago, and there were guys with a few feet of desk and they would have their bits of electronics that they put inside tobacco tin-like things. The enthusiasm of these guys! We wondered what we could bring to that market. I spoke to Robert Watts [Chord’s digital guru] and he said it’d be difficult because of the power that’s needed to make a superb DAC at that size… but then a few days later he rang and said actually he could do it. Because there was a new chip out."

Chord’s DAC chip

“There’s a big difference between our DACs and off-the-shelf chip DACs. Chip DACs are tiny piece of silicon with all the key components of a DAC onboard, but because they’re only made for a few dollars they’re relatively crude.”

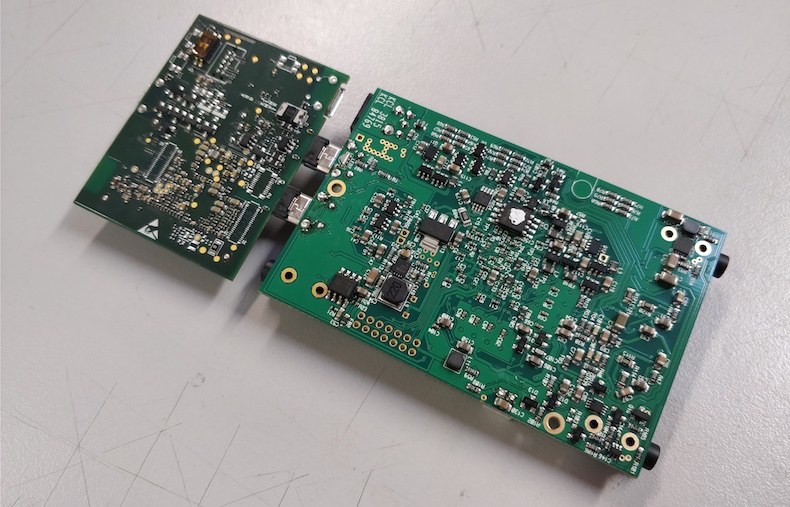

Chord’s FPGA (Field Programmable Gat Array) DAC circuitry, meanwhile, is loaded with highly developed proprietary software – which covers everything from the digital-to-analogue conversion to filtering.

John has an analogy for it.

“While normal DACs have maybe 100 digital taps, we have tens of thousands to reconstruct the waveform. If you had a map of Norway and someone gave you 100 pins, and asked you to pin over the map and get the coastline, you could do it. That’s what a chip DAC’s reconstruction of music is. But we have more and more pins, so you can get a much more accurate waveform. And we’re up to a million pins in our big stuff. The smaller the pins, the more length you get of the coastline. If you measure any coastline with a 100m point-difference, and you go down to 10m, the coastline increases dramatically."

John continues, "the first DAC we developed with Rob dissipated about 30 watts. There were four FPGAs, each one with about 100,000 logic gates, running at 3.3 watts each, and they all got hot - they were dissipating about 7 watts each. The basic problem then was making a mobile product, because the battery pack would’ve been as big as a cushion. But that was 20 years ago.

"Nevertheless, each generation of chips becomes more powerful - they have a lower voltage, and therefore need less power. So we’ve gone from 3.3 to 1.8, then 1.2. We’re at about 0.7 of a volt now. The whole idea is that you can make these chips run faster, and put lots more inside, and still have the processing power.

"When it became possible to put a high-performance DAC and headphone amplifier into a mobile product, we did. And that was the Hugo."

Finding the Mojo

"So we did the Hugo, the size of one-and-a-third cigarette packets. But some people wanted one to be more mobile. I asked Rob whether we could make something a lot less, under £400 if possible, and retain a good quality. He said he thought he could match the quality because there had been a two-year gap and a new chip had arrived. And that chip enabled Mojo to be produced. That’s really the genesis of how the Mojo came along.

"The chip is about four times as large as the chip inside Hugo. We had about 27,000 taps inside the Hugo, which is the maximum we could get into that chip. There wasn’t even space for housekeeping stuff like remembering settings! The problem with the new chip being larger and having four times the logic was that if we used all of it, it would’ve run too warm. So Rob decided to double the number of digital taps but run them at a lower rate, reducing power consumption. With a product that size, it’s all about power consumption. We wanted to give it nine hours, and we got to eleven.

"We realised the type of headphones that would be plugged into it, so we decided to give it a more moderate filtering for a slightly warmer sound than the Hugo.

“I would argue that when you actually look at its components, the Mojo is better value for money than anything else in the market," says Matt. "Normally you’ll have £10 worth of parts in a £250 product. And the difference between component costs and sales price for Mojo is considerably smaller.”

A mobile/hi-fi hybrid

“We realised there were four billion smartphones in current use when we launched it around the world. And that was our target market. We weren’t targeting audiophiles. But actually we’ve done pretty well in the audiophile market as people are using it in a system. It’s the most affordable way into Chord ownership ever.

"We haven’t really got across to the downloading, music-loving ordinary guy - and that’s what we’ve got to do. We’re working on it. It’s very hard for a company that’s not Apple to access those types of markets. Part of the challenge is explaining what a DAC is to an ordinary guy."

So recognising that Mojo was a mobile/hi-fi system hybrid, being used in traditional set-up as well as on the go, would Chord have changed anything to make the Mojo a more conventional hi-fi item?

“I don’t think we’d change anything. We physically couldn’t get RCAs in there and keep the battery the same size, and the battery can be kept fully charged as long as you turn it off when it’s not being used.

"Otherwise you’re effectively running all electronics all the time, and running the battery on charge the whole time. Historically there’s been this view of keeping everything on, not necessary now with modern electronics. If you switch it off when you aren’t using it, it has no problems with sound quality when you start it up, it’s instantly usable. That gives the battery a nice full charge cycle when it switches off, and that’s the optimum way of using any battery. That’s the only advice we’d give to prolong everything.”

The Poly partnership

In 2017, Chord released a well-performing yet relatively pricey streaming module (the £500 Poly), that attaches directly to the Mojo to gift it DLNA streaming, AirPlay, Bluetooth and microSD card playback.

“With the dedicated Poly streaming module, the Chord Mojo is now the product we always envisaged it to be," says John. " Originally I felt that the Poly would connect to a phone, but the problem was you always needed a cable. And it occurred to me that it’d be good if we could have an SD card and not use up a phone’s memory with music.

"But then we’d need a display… and a very small one. Well, the phone is the best display, so wouldn’t it be good if we could throw all information controlling the SD card up to the phone? You’d need Bluetooth or wi-fi control, or why not both? The idea came to this fairly quickly.

"We had to develop ten-layer circuit boards with tracks within tracks, planes within planes. It’s a unique product that has to settle into a wi-fi ecology, so it’s like throwing an animal that’s not been developed for an area, into the Savannah - even though it has six legs and two noses - and saying off you go. We had to keep changing and updating the software to make it sit into this 10,000-router world.

"We had a vision about how we thought the customer would use it. We thought people would configure it and leave it as it was, and not want to continuously tweak it and change settings etc. So we had to develop a GoFigure app."

Which has us begging the question, is a streaming module for Hugo 2 on the horizon? Our fingers are firmly crossed.

No way, MQA

With many DAC purveyors such as AudioQuest, Audiolab, Meridian and dCS supporting MQA (Master Quality Authenticated) – essentially a technology that can package hi-res music into files small enough to stream and download, could this be the next feature for Chord's products?

“Fundamentally, we’ve looked at MQA, and it’s not for us," says John. "It’s a clever idea as a packing system. But you don’t need to pack your audio down. It solves a problem that’s not there now. We looked at it and we thought it was inferior to what we were doing, so we haven’t touched it."

“We’d have to undo 20 or 30 year's-worth of work to produce a product to meet the requirements of the format," says Matt. "We’ve been quite open and said we would happily integrate MQA into our products if there was a proven benefit to do it, but as yet no-one can prove that benefit in a simple way that’s clear, so it’s not worth pursuing. We’ve taken technologies from every aspect of the industry to benefit customers' listening, but this just isn’t one of them.”

Pushing price points?

Of course, one way to perhaps get into the pockets of the ‘ordinary guy’ would be to challenge the likes of iFi and AudioQuest in the budget market…

“We have sound quality standards to adhere to," says Matt. "To produce a product at a lower cost than Mojo, we’d have to do something quite drastic. We wouldn’t put a $5 chip in there. So would customers accept a product that only had, say, a 2-hour battery life? One that didn’t have all of the inputs and outputs? One that could only drive sensitive IEMs?”

John chips in, "it’s a philosophy. It’s like John Ruskin said, 'there is hardly anything in the world that some man cannot make a little worse and sell a little cheaper'. It's unwise to pay too much, but it's worse to pay too little.”

MORE:

Welcome to What Hi-Fi?'s British Hi-Fi Week

Becky is a hi-fi, AV and technology journalist, formerly the Managing Editor at What Hi-Fi? and Editor of Australian Hi-Fi and Audio Esoterica magazines. With over twelve years of journalism experience in the hi-fi industry, she has reviewed all manner of audio gear, from budget amplifiers to high-end speakers, and particularly specialises in headphones and head-fi devices.

In her spare time, Becky can often be found running, watching Liverpool FC and horror movies, and hunting for gluten-free cake.