What is a DAC? And why do you need one anyway?

A vital cog in your digital audio system explained

The latest hi-fi, home cinema and tech news, reviews, buying advice and deals, direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

A DAC (digital-to-analogue converter) is an audio component that converts digital music data into analogue signals that speakers and headphones can play, because human ears and audio equipment require analogue sound waves, not binary “0s and 1s”.

Most digital devices (phones, computers, TVs) already have a built-in DAC, but those internal DACs often don’t process audio as accurately as a dedicated external DAC, so upgrading to a separate DAC improves sound quality by performing a higher-fidelity conversion.

In short, DACs play a large part in making digital music worthwhile!

Article continues belowTherefore, any device that acts as a source of digital sound, be it a CD player or Blu-ray player, digital TV box or games console, laptop or computer, phone or portable music player, needs a DAC – either one that is built-in or an external one connected – to convert its digital audio to analogue before it can be output.

Most everyday, multi-tasking digital products have DACs built-in, but the problem is that these DAC circuits are typically not efficient enough to accurately process the conversion and thus do justice to the original recording.

These are do-it-all devices that have plenty else to process, of course, so we can't expect them to prioritise digital audio conversion and playback above all else.

That's why upgrading to a separate, external DAC – one whose only job is to carry out the conversion process – can be the simplest way to get the most out of digital music, whatever your setup.

The latest hi-fi, home cinema and tech news, reviews, buying advice and deals, direct to your inbox.

Convinced already? You can dive straight into our best DACs buying guide. Want more of an education? Below we explain how a DAC works and why you should invest in one.

What is a DAC? What does it do?

The sounds we hear on a day-to-day basis – traffic, instruments, that baby screaming on your otherwise peaceful commute – are transmitted in soundwaves, which travel through the air to our ears in a continuously varying analogue signal.

Analogue audio recordings were stored on the likes of shellac (and later, vinyl) discs, and then on magnetic cassette tapes, but the fragility and unwanted noise of these formats made way for something new. The CD was born, kickstarting the digital audio revolution in the process.

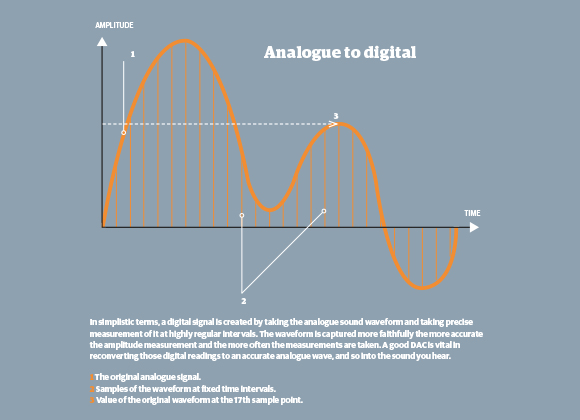

Digital audio takes a very different approach to that of analogue. Digital music files are usually found in the form of Pulse Code Modulation (PCM) and are created by measuring the amplitude of the analogue music signal at regular intervals.

The value of the amplitude is represented as a binary number (comprised of 1s and 0s) and the length of this number is often referred to as bit depth. The timing of the measurement intervals is called the sampling rate.

When recording a standard CD, say, a sample is taken 44,100 times per second. Each of these samples is measured to an accuracy of 16 bits, storing the results in a 16-digit binary format. So, "CD quality" audio refers to 16-bit/44.1kHz recordings.

Record high-resolution audio, on the other hand, and you’ll take a step up to 24 bits, with a sample taken as often as 192,000 times per second, making for 24-bit/192kHz recordings.

Digital audio data can be stored in a variety of sample rates, bit depths, encoding and compression formats – but no matter how it’s done, it is the DAC’s job to make sense of it all, translating it as accurately as possible from its binary format to return it as close to the original analogue recording as it can.

Why do I need a separate DAC?

While it’s true that just about every piece of digital kit features a DAC, it’s just as true that not all DACs are created equal. For starters, they might not support all file formats and data rates. And, as we've alluded to above, they could simply not be all that great at their conversion job.

Poor converters can introduce unwanted noise during playback due to poorly designed circuitry, not to mention add extra distortion due to jitter. (Jitter is best defined as digital timing errors. The precise timing of a digital music stream is vital to high performance, and if that isn’t done properly – usually because of poorly designed digital clock circuitry – performance suffers.)

Jitter problems can arise every time a digital signal travels around a circuit board – and it’s particularly troublesome when the signal is transferred between devices. In recent years we’ve seen the rise of the asynchronous DAC, which takes over timing duties from any computer it may be connected to for exactly this reason.

The digital clocks found in dedicated hi-fi DACs tend to be more accurate than those used in the average PC, so generally the conversion process will be performed much more faithfully – and definitely so in the case of the very best DACs.

WAV, FLAC, DSD: source material is everything

Of course, to get the most from a DAC you need to start out with good source material – don’t expect miracles if all you’re throwing at a converter is 128kbps MP3s or Spotify streams. In fact, better decoding of such a compressed signal can make any sonic shortcomings more obvious.

You’ll hear optimum results with CD-quality content or, better yet, hi-res audio, which is often stored in FLAC, WAV or ALAC (Mac) lossless PCM formats, or alternatively DSD if you prefer. All the audio file formats are explained here, but very briefly...

DSD, or Direct Stream Digital, is an alternative to PCM and was originally conceived for Super Audio CD (SACDs) – a format championed by Sony and Philips in the late 1990s and into the noughties.

It’s a much more niche format, differing from PCM by offering a bit depth of just one, but much higher sampling rates – commonly DSD64 at 2.8MHz and DSD128 at 5.6MHz.

The arguments as to which encoding system is better continue to rumble on. Suffice it to say, if you’re someone firmly settled in the DSD camp, it’s worth checking whether the DAC you’re considering supports it; most, but not all, do.

What type of DAC is right for you?

DACs come in all shapes and sizes and offer varying levels of input options and functionality, so you’ll need to think about how you want to use one, not to mention the budget you have set aside.

Compact USB or USB-C DACs offer portability and convenience at a reasonable price. They include USB sticks, such as Audioquest's highly regarded DragonFly range, which starts at the five-star Audioquest DragonFly Black and goes up to the DragonFly Cobalt. These plug straight into a laptop (or to a phone, via a converter adaptor),

Or you can get a wireless DAC like the five-star iFi GO Blu, which can connect to a source (though not your headphones) via Bluetooth, taking one wire out of the equation.

Some draw the power from your computer or phone, so there’s no need for an extra power source, and they largely keep connections simple, with just a headphone socket and possibly a line-level output for hooking up to powered speakers or a hi-fi system.

If you are considering upgrading your personal listening setup, note that the performance of good wired headphones with a DAC will invariably surpass that of wireless headphones.

If you need more connectivity and aren't concerned about taking your DAC around with you, a desktop DAC like the Award-winning Chord Mojo 2 (which is actually also portable) might be more suitable.

While usually bigger and require their own power source, they often offer several additional digital or analogue audio inputs alongside a USB input for connecting to your computer. Some, like the iFi Zen DAC V3, can be either USB or mains powered.

Keep an eye out for a DAC with a headphone amp built-in if you want to listen through headphones – most but not all DACs offer this as an option.

Our Award-winning Chord Qutest DAC, for instance, doesn't have headphone amplification or sockets, instead designed to slip into a speaker-fronted system, between a digital source and amplifier, to enhance performance.

Finally, some DACs are born to work as part of a bigger home audio system. These will usually have even more inputs – particularly more niche sockets such as AES/EBU – and potentially more features, including perhaps a volume control so they can also be used as a pre-amp.

They'll support the full range of high-resolution music formats or have Bluetooth connectivity for streaming wirelessly from your smartphone or tablet, though both of these offerings are also increasingly offered by portable and desktop units nowadays. These home DACs tend to be at the higher end of the market, so should deliver higher performance, too.

These can range from the sensible (the Chord Hugo 2, say) to the extravagant (the Chord DAVE) or, if money really is no object, the Nagra HD DAC/MPS. Ready to make your purchase to improve your portable phone, desktop computer or home hi-fi system? Check out our expert pick of the best DACs in our handy buying guide.

MORE:

7 reasons why a DAC could be your music purchase of the year

Our pick of the best headphones you can buy

Everything you need to know about high-resolution audio

Forget AirPods, this is the hi-fi accessory every student should be taking to university

Verity is a freelance technology journalist and former Multimedia Editor at What Hi-Fi?.

Having chalked up more than 15 years in the industry, she has covered the highs and lows across the breadth of consumer tech, sometimes travelling to the other side of the world to do so. With a specialism in audio and TV, however, it means she's managed to spend a lot of time watching films and listening to music in the name of "work".

You'll occasionally catch her on BBC Radio commenting on the latest tech news stories, and always find her in the living room, tweaking terrible TV settings at parties.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.