Marantz is celebrating its 60th anniversary, and the story behind the founding of one of today's best-known hi-fi and home cinema companies is a familiar one: Saul B Marantz – music lover, amateur musician and photographer – started making hi-fi products in the early 1950s simply because he was sure he could do it better.

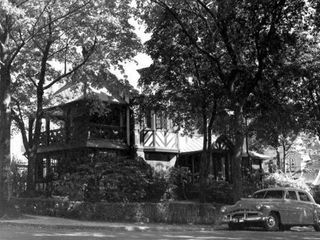

In fact the history goes back further than that: born in 1911 in Brooklyn, New York, Marantz (seen above around 1940) starting building audio equipment soon after leaving military service during World War II.

Here's a specially-produced video covering 60 years of Marantz history:

Saul Marantz: from in-car to in-home

Legend has it that, having moved to the New York suburb of Kew Gardens, Saul Marantz decided to improve the radio in his home by removing the set from his 1940 Mercury car and installing it indoors – after all, he hardly ever listened on the road!

Making the radio work involved building some additional electronics, and out of this came four years' work leading to the design of his Audio Consolette, a high-quality preamplifier.

This was in the early days of the LP, which was launched in 1948, and the equalisation curves – the pre-emphasis added to overcome the limitations of the record and give high fidelity sound, and which required re-processing on playback – were yet to be standardised.

LP? 45rpm? Early format wars

Depending on which company's records you played, different settings were required to get the best sound, not to mention that in the early days of the LP, there was a format war between Columbia's 33.3rpm LP and RCA Victor's 45rpm disc.

It would be a while before efforts were made to standardise the pre-emphasis, and thus the equalisation curve required on playback: the Audio Engineering Society set its own 'AES curve', designed to be adopted by amplifier manufacturers, but Columbia had is own curve, as did RCA and others.

In fact, the Consolette had settings for no fewer than 36 types of LP and 45rpm equalisation curves: it was valve-driven and mono, of course – the stereo LP was still some years off, arriving in 1958, and it would be almost a decade and a half before Marantz started making 'solid state' (or transistor-based) components.

The genius of the preamplifier designed by Saul B Marantz was that it had settings for all these curves: he initially made the device for his own use, but word spread, and people started asking him to make them one, too.

In 1952 Marantz decided to make 100 units of the Audio Consolette, selling at $153. He was still operating on what was almost a kitchen-table scale – the products were actually made in the basement of his Kew Gardens home (above) –, but in less than a year more than 400 had been made, such was the demand.

Not surprisingly, Marantz decided to step up to a commercial scale, and in 1953 the Marantz company was started. In 1954 it launched what was by then called the Model 1 preamplifier, the production version of the Audio Consolette, selling for around $150.

In those days it was common to buy products either for installation into pieces of furniture, or complete with a cabinet for standalone use: the Model 1 was $20-30 more if you wanted it with a cabinet.

Also not surprising is that the Model 1 preamplifier was followed by the Model 2 mono power amplifier, seen above with the Model 1 in a recent Marantz history display.

By now Marantz had been joined by engineer Sidney Smith, who became the chief engineer for the power amp, and shared Saul Marantz's obsession with making the most of audio quality to deliver the best possible musical performance.

Selling for around $200, the Model 2 delivered 40W, or 20W when used in triode mode, and the basic design would go on to be at the heart of the less powerful Model 5 of 1958, designed for use in multi-amplifier systems to make the most of the then-new stereo system.

But I'm getting (only slightly) ahead of myself: in the intervening period Marantz had built a two-way offboard electronic crossover, the Model 3, and an upgrade power supply for use with the Model 1 or Model 3. Oh, and had moved to new premises at 25-14 Broadway, Long Island, where it seems there is now a branch of Dunkin' Donuts!

1958 also saw the arrival of a stereo adapter for the Model 1, but it was the end of that year before Marantz launched what would be seen as the first of a run of classic products, the Model 7 stereo valve preamplifier (above). Selling for $249 without cabinet, it was followed by the Model 8 stereo power amp in 1959 – effectively two Model 5s in a single chassis, and delivering 2x30W for $237 (or $246 fitted with a grille cage over the valves).

The amp would later be improved to create the 1961 Model 8B, with a heady 5Wpc power increase from a circuit base on that of the Model 9 mono power amp, which had been launched in 1960, and was capable of 70W maximum output.

The Model 9 (above) was also notable for being the first Marantz power amp with a front panel – until then, they'd been very industrial-looking devices designed to be hidden away – and for the first appearance of the Marantz 'porthole' power meter, a styling cue still found on the company's 2013 products.

But one of the most sought-after Marantz products was just around the corner: in 1961 Richard Sequerra had joined the company, and together Marantz, Smith and Sequerra worked on the Model 10, the company's first tuner for the FM stereo radio service, launched in the States in 1961.

In 1962 the company showed a prototype of the Model 10, using an oscilloscope tube display for tuning/multipath indication, and in 1963 the Model 10B was launched, complete with 3in oscilloscope.

The price? $650, but this hardly covered the massive investment the company made in developing the tuner over more than three years: in a later interview Marantz would say that even his wife had to put up money to keep the company going, and that the 10B finally sold was an attempt to take the Model 10, of which less than 100 were made, and find a way of making some money from the thing with a little judicious juggling of components.

The tuner that almost cost the company

He said that 'Many people feel, to this day, that the 10B was the best tuner ever made. When they were new, the last price [in the early 1970s] was about $750, retail, and I stll felt I was putting a free hundred dollars in every box.'

Marantz also noted the way the price of the product rose on the collector's market, saying that when he was in Japan in the mid-70s, used 10Bs were already selling for 'about $3700' and that he'd later heard of them changing hands for 'over $10,000'. Prices may have softened a little, but you should still expect to pay $5000 or more for one in excellent condition, and probably a lot more for one of the rarer versions such as the original Model 10 or the version with a rack-mount faceplate.

Despite the fact that Marantz made thousands of Model 10Bs, or perhaps because it made so many, making a loss on each one, the product almost destroyed the company, and an offer from Superscope to take over the company came just at the time when Marantz said 'we were thinking of closing up, of finding some way to get out'.

Superscope took over the company in 1964, moving it from New York to California the next year. In 1966 Marantz products began to be made in Japan in partnership with Standard Radio (which would nine years later change its name to Marantz Japan), and in 1968 Saul Marantz retired as president of the company bearing his name.

But talking of new technologies, Marantz also had a stake in the TV market, as this set on show at the history exhibition demonstrates: starting in the black and white era, it still had TVs on its books well into the age of the flatscreen,

and in later years built a strong reputation as a manufacturer of projectors, with models all the way up to the massive VP-10S1 below.

Anyway, back to the history, and 1965 had seen the arrival of the first solid state Marantz products, in the form of the Model 7T preamp and, a year later, the Model 15 stereo power amp, and in 1968 came another of those classic Marantz products, and the start of a long line of receivers: the $595 Model 18.

Solid-state, and with an FM tuner built-in, it retained the oscilloscope and had the company's Gyro Touch flywheel tuning control, and in later years Marantz would take the tuner section from this receiver and attempt to recreate the appeal of the Model 10B with the Model 20.

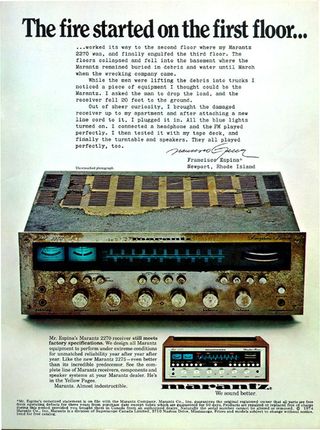

It would go on to be the first of many 'battleship' Marantz receivers, such as the 2600 (above) and the 2275, and the company was proud of the solidity of build and reliability of its products, as shown in the 'testimonial' ad below.

Changing hands

The 1964 sale to Superscope would be the first of several changes of ownership for Marantz: in 1980 Superscope sold its 50% holding in Marantz Japan, and trademark and marketing rights worldwide (excluding the USA and Canada) to Dutch company Philips.

The story goes that Philips USA didn't want a fifth brand – it already had Sylvania, Philco, Philips and Magnavox 'on the go', as I explained in my piece earlier this year marking the end of Philips' consumer electronics activities – and it would be many years before Marantz was again completely united.

By the time Philips effectively took over selling Marantz to most of the world, the company had already been joined by someone set to be a significant figure in the its future development.

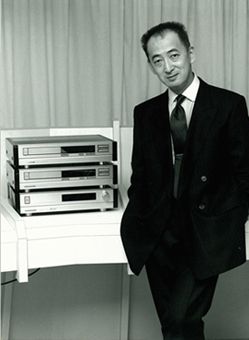

Ken Ishiwata, seen left way back then, moved to Marantz Europe, having been headhunted from Pioneer in 1978, as technical co-ordinator.

He was sent back to Japan for three months to learn about the Marantz way, and as he told me in a piece I wrote celebrating his 30 years with the company, 'The Marantz understanding of amplifiers was way beyond me: the company spent five years training its engineers in the American way of making amplifiers.'

Within two years Ishiwata had been appointed Product Development Manager, not least because both good audio and the Marantz ethos was deep-seated. He recalls that 'by the time I was ten, and the first stereo LPs were being made, I was making my first amplifier.

'About that time, a friend of mine's father, who was a real audiophile with his own wonderful listening room, invited me round to hear a record by Julie London' – a singer whose music Ishiwata still uses for demonstrations getting on for 40 years later.

In fact, her recording of Come On-A My House, one of those first tracks Ishiwata heard, was a focal point of his recent '60th anniversary' demonstrations to Marantz and Denon retailers.

'I knew the disc, but as soon as it played, it was like Julie London was there. 'Wow!' I said, "What did you change?" And he pointed to a gold fascia – it was the Marantz Model 7c preamp"

For the past 35 years, Ishiwata and Marantz have been inextricably linked: he was there when Philips (and thus Marantz) started making their first CD players, starting with the CD-63 (above).

Ishiwata says 'That was another great opportunity for me: I had been working with analogue audio until then, and didn't know anything about digital. I learned so much from the Philips engineers.'

Also around this time Ishiwata was contacted by Saul Marantz, by then in his 70s, who said 'I have done as much as I can with mono and stereo LPs; now it's your turn to do something with compact disc.'

The start of the Special Editions

With the torch so clearly passed on to hime from the company founder, Ishiwata who started the Marantz concept of specially-tuned products, though he admits the whole idea started out of expediency.

Sometime around the mid-1980s, just a few years after the launch of CD, Marantz had a stockpile of its CD-45 players. These used Philips' 4x oversampling 14-bit Continuous Calibration technology, at a time when the Japanese rivals were trumpeting their use of 16-bit.

Consumers automatically assumed that 16 was better than 14, and so 'We had this huge stock of 14-bit players, and they weren't selling. Some of my colleagues wanted to dump them on the market for just £100 each, but I said 'We're not going to do that' – instead I spent just £8 apiece tuning them, then took the tuned models out to reviewers and retailers as 'the most musical CD player in the world"'.

LE becomes SE becomes OSE becomes KI Signature

The tuned model – the CD-45LE – shifted 2000 units in a fortnight, and the idea led to a stream of Special Edition models, both from Marantz and from other companies. In fact, so many of the rivals were jumping on the SE idea that Marantz started calling its tuned products OSE – Original Special Edition – to show it got there first.

However, no rival could market a KI Signature product, the idea being to select affordable models with potential from the range, tune them using 'cost no object' strategies, and still sell them at a sensible prices.

Tuned to sound the way Ishiwata wanted, rather than compromised by cost or other concerns, the KI Signature products came with exclusive badging and a signed certificate.

Not only did they prove to be best-sellers, but for many people the 'KI' range also brought Ishiwata out from the Marantz backrooms and into the spotlight.

And it's clear he still has a lot of affection for the models, despite initial reservations from some that consumers wouldn't pay a significant premium for a tuned product As Ishiwata says, 'Remember the first KI Signature product, the CD-63MkII KI Signature? I think it's still one of the most musical CD players we've produced.'

Yes, I remember it – from overhearing the initial discussions of the idea, through 'come and hear this' sessions involving early morning flights on unfeasibly small planes from London to the almost as small Eindhoven airport, to the arrival of the player on the market. Throughout the process, it was clear Marantz – and Ishiwata – was on to something special.

I also get the feeling that the fact the first Signature model, seen above in its very limited copper finish, shares a model number with the very first Marantz CD player, the CD-63 of 1982, won't have been lost on Ken…

In Ishiwata's time at Marantz, the company has produced many classic models, and some striking ones, too, from the TT 1000 turntable (above) to the NA-11S1 network music player (below), both of which featured in his celebratory demonstration.

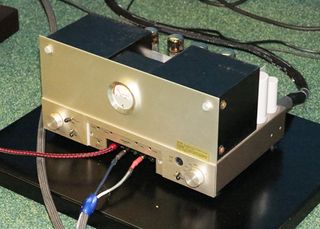

Then there was the compact MusicLink range of the early 1990s, the battery-driven SC-5 preamp and SM-5 power amp of 1994, the massive Project T1 valve power amps (above) of the same year, and most recently the new Consolette system (below), launched last year.

And Marantz has changed hands once or twice again during its history, the US operation being unified under the Philips-owned Marantz Company of Japan in 1990, and in 2001 bought out by Marantz Japan to create Marantz Japan Inc. Finally in 2002 Marantz and Denon came together to form D&M Holdings, which changed again more recently to D+M Group. Phew!

Saul B Marantz 1911-1997

Saul B Marantz died in January 1997, aged 85, just a year after Marantz had launched replica versions of some of his earliest designs as Marantz Classics.

In his retirement from the company he started, he'd also found time to found high-end speaker manufacturer Dahlquist, from which he retired again in 1978, and almost to the end of his life was developing and helping new speaker brands.

But from the early days of home-made Consolettes to the modern-day iPod/streaming system of the same name, engineered by Ishiwata, now Marantz Brand Ambassador, as a 60th birthday tribute and packed with references to classic Marantz products (plus some very up-to-date technology), the Marantz way of thinking has been the same.

As Terry O'Connell, Marantz MD, puts it, ‘When one of our engineers, either in Japan or Europe, auditions a transformer or a DAC, for example, they're not interested whether it’s good or bad, only how it performs with other components.’

She explains that, ‘Developing a new product is like assembling a sports team: with enough money, you could get the best players in the world but that doesn’t mean they are going to win. The whole team must interact harmoniously, each individual player must be excellent, but must also help ensure all his teammates perform to their best abilities as well.

‘All Marantz design engineers understand this and fortunately, we have a very experienced team, especially in Japan. They live and breathe this philosophy at every stage of new product development.’

Ishiwata demonstrated it with music at the recent dealer conference, starting with pre-LP mono recordings (Benny Goodman at Carnegie Hall in 1938), direct-cut discs and even a 12in single, played on a Marantz TT1200 turntable through Model 7, Model 9s and Tannoy Prestige speakers.

The demonstration progressed through CD and SA-CD to DSD downloads played on the NA-11S1, today's top-end Marantz preamp and power amps (run bridged), and Boston Acoustics M350 speakers.

Ishiwata has also played a major part in the design of those speakers – after all, one of his very first tasks at Marantz had been as a development engineer for the company's speakers, at the time coming from the States and not at all well-suited to the European market.

These days the Boston speakers are designed with a team of Europe-based consultants, and Ishiwata knows their characteristics very well, which is why he used them for this demonstration in one of his typical ‘difficult room’ toe-in set-ups – in other words, almost facing each other!

Of the Marantz design process, he says that ‘Of course we have electronic tools and instruments, but these can only measure sonic parameters in a static way.

'Instruments can only measure instantaneously, like a camera taking a picture of a dancer.

‘The image will be extremely precise, but it will show nothing of the dynamics, speed and rhythm of the dancer. Music is also dynamic. Its tone, volume, pitch, and intensity continuously change.

‘That’s why every time we work on a product, we measure its quality by referencing a piece of music that we absolutely know sonically and perceptually from its original source.

'Only then can we relate the character of each component as a part of a whole.”

Or as Terry O’Connell puts it, 'On every piece of printed literature we publish, on every website and every advert, we state Because music matters. But this isn't just a slogan, or a piece of marketing.

'It's a philosophy that has driven our company from the very beginning, and I believe it's what makes Marantz stand out from other audio solution manufacturers.'

Written by Andrew Everard