Bach with more bite: how to listen to classical music's greatest ever composer

Hi-fi listening lessons from the GOAT

The latest hi-fi, home cinema and tech news, reviews, buying advice and deals, direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

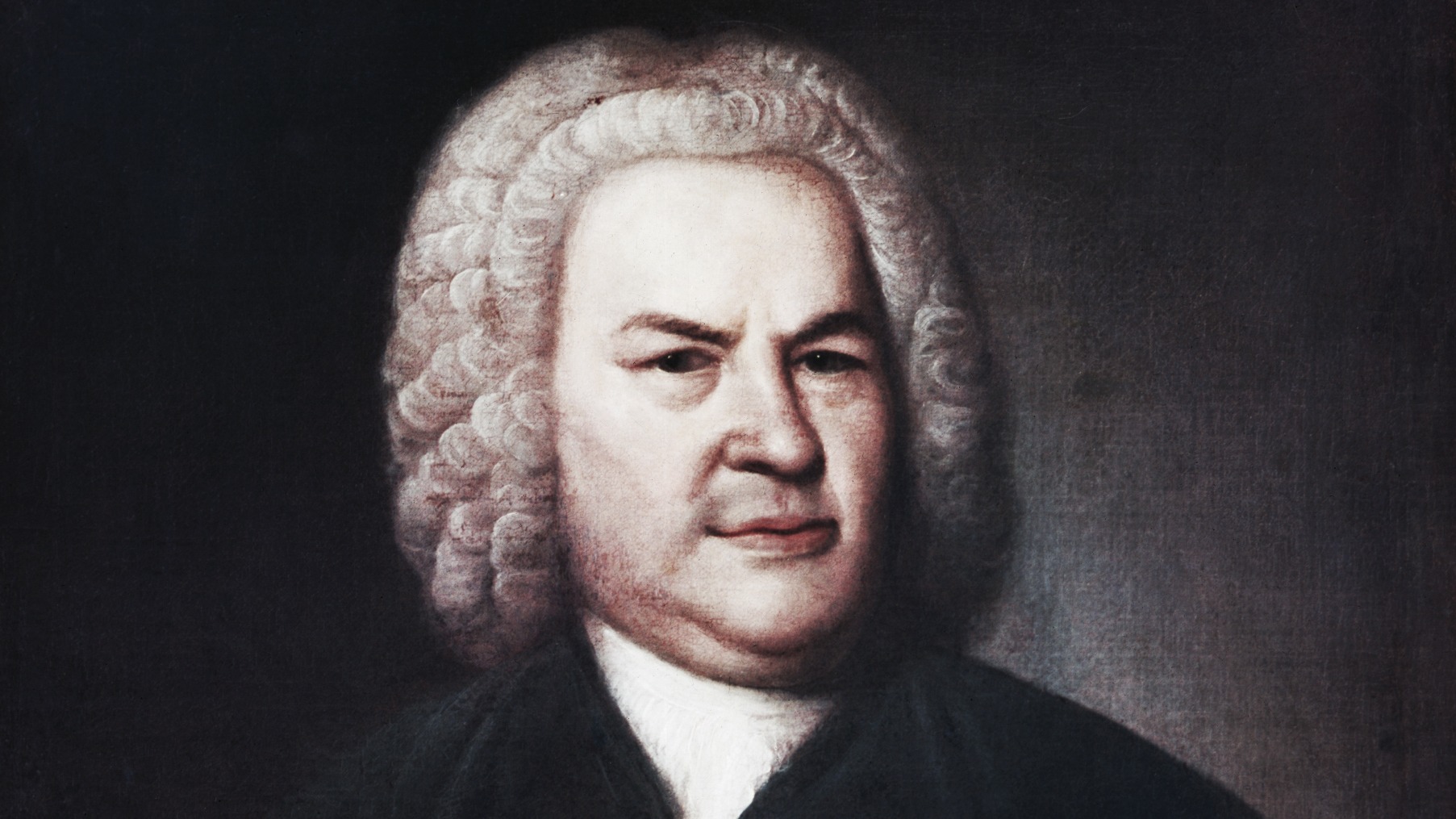

Ask any self-respecting classical music aficionado who the greatest composer of all time is, and they’ll usually whittle down a shortlist of three key names: Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, Ludwig van Beethoven, and J.S. Bach.

Press them further on the issue and they will probably, though by no means inevitably, place Beethoven at number three and Mozart at two, before giving Bach the lion’s share of the plaudits in that coveted number one spot.

That’s all up for much contentious debate. My piano teacher, for instance, wouldn’t let me play a note of Mozart, considering it too perfect to be mangled by my ham-like fists.

That said, Classic FM and the BBC’s Classical Music sister site both consider Bach to be at the top of the classical tree; while Anthony Tommasini, chief classical music critic for the New York Times, proclaimed Johann Sebastian to be the greatest composer of all time in 2011.

I’m not here to settle that particular debate (I could, of course, given the obvious sway my name holds within scholarly circles). Instead, I’m here to espouse the virtues of Bach as a composer you need to add to your listening line-up, both for the purposes of testing your system’s capabilities and, perhaps more importantly, so that you can enjoy both his music and your setup to the fullest extent.

What's the (counter)point?

When she wasn’t barring me from bashing out a bit of Wolfgang Amadeus, my former teacher imparted some insightful wisdom regarding how Bach’s music (not subject to the same protection) should be played, and it has always stuck with me as being equally revealing with regard to how he should be heard.

In essence, you’re dealing with a pair of hands but up to four ‘voices’, meaning you’ve got the challenge of bringing out two distinct passages with your left mitt and two distinct passages with your right. Each must shine in its own regard, with every one of the distinct but interwoven melodies interacting with the other while retaining its own unique identity.

The latest hi-fi, home cinema and tech news, reviews, buying advice and deals, direct to your inbox.

This is the basis of what clever people with spectacles and bad haircuts would term ‘counterpoint’, and nobody before or since has mastered the concept quite like Bach.

There are literal books devoted to the subject, but in a nutshell, it’s the idea that various melodies are operating concurrently within the same overarching arrangement. Pick them apart and they work as their own distinct tunes; put them all together again and you end up with a cohesive, complete whole. Paintings within paintings, wheels within wheels… something about windmills.

Bach’s works make use of general polyphony (lots of textures and passages all playing at the same time), but his specific mastery of counterpoint is what makes him, to many, the undisputed GOAT.

That is the skill a musician, particularly a pianist or, in the case of the Toccata and Fugue in D Minor, an organist, must master if they are to play Bach ‘properly’.

That, in turn, should be translated by the system playing a given recording. So often we listen out for whether instruments sound mechanical or whether they sound as though they are being played by an actual human being – and that necessity is amplified when dealing with a musician tasked with teasing out all of those various strands to full effect.

All the world's a stage

One useful way to think of counterpoint, and whether your given product or setup is handling it ably, is to think of that classic Shakespeare quote from As You Like It: “All the world's a stage, And all the men and women merely players. They have their exits and their entrances…”

That last bit is the key. One of the clearest windows into Bach’s music is to listen out for the entry point of each melody and to follow it to its conclusion. That’s quite easy to do with something such as the Adagio from the Concerto in D Minor, wherein the left-hand melody remains relatively simple while the more expressive right takes the spotlight.

For something more complex, check out the second half of the Little Fugue in G Minor, wherein you should be able, especially if you follow along with the sheet music, to detect at least three, ideally four, voices handling their own respective tunes – a bit like when an a capella group sings different lines to the same song and it all still fits together.

Bach often signifies the start of these passages with two clear signpost notes before moving into an extended ascending or descending run, so it’s useful to listen out for those markers when you’re trying to distinguish when a new passage has started. Again, a good system will announce passages as a trumpeter heralds news; a bad one will allow them to be lost in the melange.

That’s something you really don’t want. With so many voices and complex runs working alongside one another, you can’t afford a muddy or cluttered setup which blurs the lines between notes. Clarity and organisation are key, so that each stroke of the keyboard has its own distinct start, middle and well-defined end.

If all this talk of counterpoint and polyphony is too much for you, it can be useful just to step back and return to basics by asking the simple questions. Is this organised or cluttered? Is it clear and well-delineated or messy and soft? Am I emotionally engaged by the music? What does ‘J.’S’ stand for, anyway?

Going back to Toccata and Fugue in D Minor is handy if you want to assess the questions above, especially as the organ is a less forgiving instrument than the piano in terms of where notes begin and end. A decent pair of headphones, such as the Beyerdynamic DT 990 Pro X, will excel in this regard. They are subtle and revealing enough to tease out each individual note with laser-like precision.

If you seek something piano based, then any of Glenn Gould’s interpretations of The Goldberg Variations will do just fine – they generally stand up as, to this day, the gold standard of playing Bach. Play the music through, say, the beautifully balanced and wonderfully insightful Acoustic Energy AE300 MK2 standmount speakers, and you should start to understand the very mechanics working away behind the overall ensembles.

Bach with more bite

As is the case when great music meets great hi-fi, something of a symbiotic relationship emerges. Yes, you're using the music to reveal more about the capabilities and character of your setup, headphones or anything in between; but you are also using said product(s) to get you closer to the music itself. That's sort of the point, after all.

Bach isn't always the easiest beast to get your head around, but you might find that giving him a go on with some proper hi-fi reveals those quirks and qualities that you might have otherwise missed. Listening to the greatest composer of all time through your iPhone's speakers, let's be honest, doesn't exactly do him justice.

Get hold of the proper equipment, and you'll start to hear how those dizzying complexities and interactions work, revealing the genius of a composer whose talents have yet to be surpassed in the 340 years since his birth. Bach can be a tough nut to crack – but, as can so often be the case with challenging artists and/or genres, maybe you just haven't been listening to him in the right way.

MORE:

The deal with Debussy: why the maestro's works are so perfect for testing hi-fi

Harry McKerrell is a senior staff writer at What Hi-Fi?. During his time at the publication, he has written countless news stories alongside features, advice and reviews of products ranging from floorstanding speakers and music streamers to over-ear headphones, wireless earbuds and portable DACs. He has covered launches from hi-fi and consumer tech brands, and major industry events including IFA, High End Munich and, of course, the Bristol Hi-Fi Show. When not at work he can be found playing hockey, practising the piano or trying to pet strangers' dogs.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.