Sound+Image Verdict

The new Stax flagship, the SR-X9000, raises the bar for an electrostatic earspeaker system, beginning with a new version of the company’s metal-mesh electrode system.

Pros

- +

Spectacular detail

- +

Thrilling transparency

- +

Balanced tone overall

Cons

- -

Requires driver unit

- -

Significant combined price

Why you can trust What Hi-Fi?

This review originally appeared in Audio Esoterica magazine, one of What Hi-Fi?’s Australian sister publications, available in print and digital editions Click here for for a Readly special offer, including access to Audio Esoterica's digital editions.

First a declaration: Stax enabled one of my first hi-fi writing successes. It was the late 1980s, and I had been taken on as Assistant Editor for What Hi-Fi? magazine, located then a short walk from the Thames in Teddington, West London. After several years on Electronics Today International I was thrilled to have pushed open the door of more audio-based publishing, but the then-Editor of What Hi-Fi?, Simon Davies, may have had a sadistic streak, as the first test he allocated to me was an enormous group of some 40 blank cassette tapes, to rate using WHF’s famous five-star ratings for sound, build, and value, to deliver a final verdict ranking all 40 blank tapes in order of performance.

This Herculean task would have been impossible using the budget Aiwa cassette deck and half-decent Sennheisers that I owned at the time, so I leveraged the power of the publication to call in the very best tools for the job. For the cassette deck, the brand required was obvious – Nakamichi. My memory is not 100% here: I know the deck I used was not the legendary Dragon, as I played with that later; I’m pretty sure it was the almost equally impressive ZX-9.

For the headphones, there was not only an obvious brand but one clear model for the job; indeed I was instructed to accept no substitute not only by editor Simon and Tech Ed Andrew Everard, but by the extended and elevated reviewers of then sister titles New Hi-Fi Sound and Hi-Fi Answers, which included the likes of Keith Howard, Jonathan Kettle, Malcolm Steward, Jimmy Hughes, Alvin Gold (noted electrostatic speaker enthusiast), and Paul Miller. I was to learn much from my contacts with these writers over the ensuing years, but the very first recommendation from those I consulted was that I should tackle my task using Stax SR-Lambda Signature earspeakers.

It was the first time I had used electrostatic designs and, as is the common experience, they were a revelation as to the sound quality that can be delivered by headphones – or ‘earspeakers’, as Stax prefers to call them. Their clarity and detail made it possible, via endless days of popping cassettes in and out to compare the recording quality of four pieces of music and the hiss levels behind them, to deliver a confident final ranking of all those blank tapes.

So on my first big hi-fi assignment, it was Stax that got me over the line.

In the round

Stax no longer makes those specific Lambda Signature earspeakers, though the series lives on in the three current SR-L models of the Lambda-Advanced series. For many fans it is their oval sound elements and rectangular headshells which epitomise the Japanese brand.

But the company has always had circular designs on its books as well, and the current round ‘Omega’ series outranks the rectangular models as the true flagship Stax designs.

The latest hi-fi, home cinema and tech news, reviews, buying advice and deals, direct to your inbox.

The earliest Stax earspeakers were also round: the SR1 shown at the Tokyo Audio Fair in 1959, also the SR-3 model which cemented the company’s reputation for headphones in 1968.

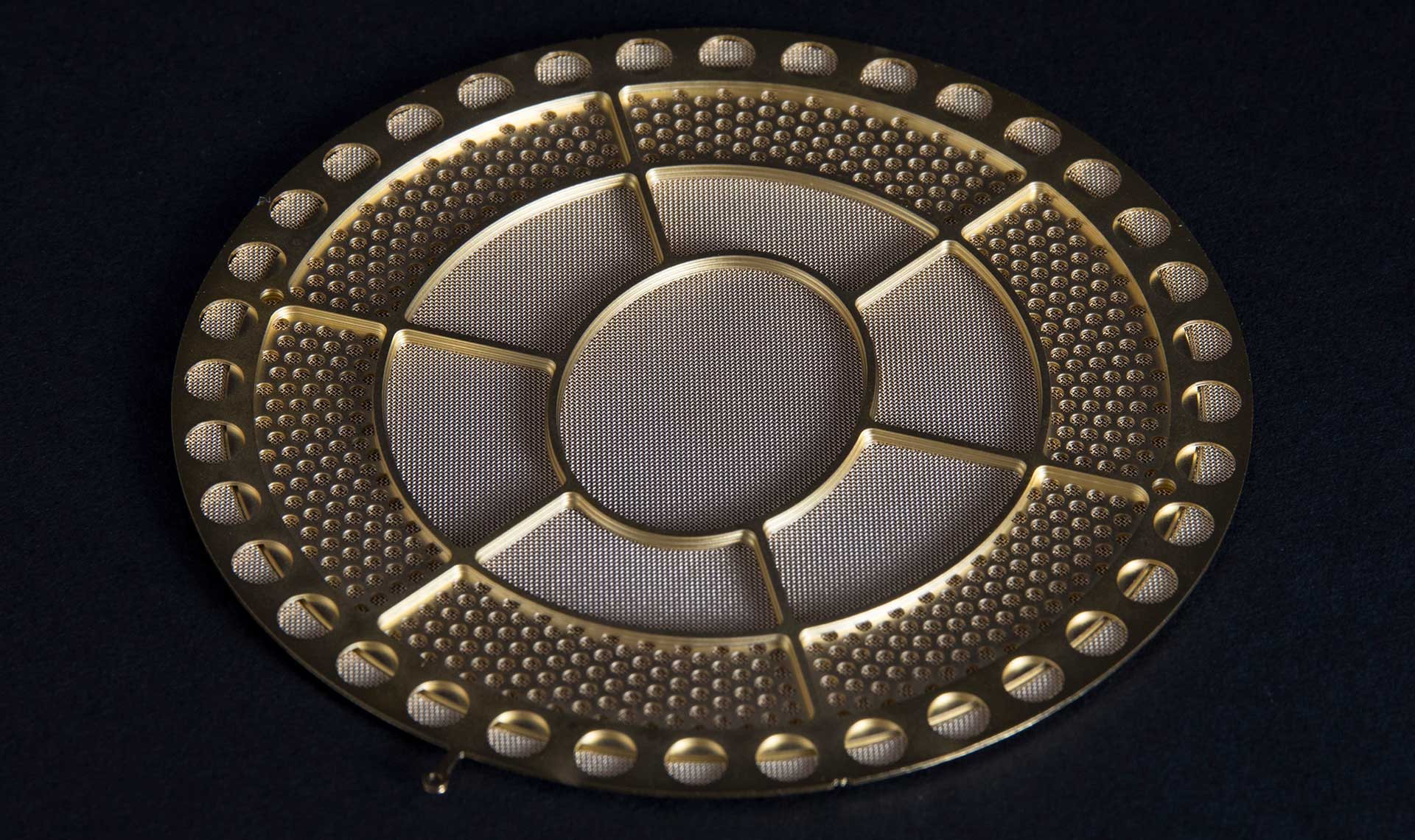

Stax first tried using metal-mesh electrodes, as compared to more solid ‘hole-punched’ stators, with the SR-X in 1970, and returned to them in 1993 for the very first of the Omega series, the SR-Ω. Its 90mm-diameter metal-mesh electrodes then represented perhaps the largest driver delivered in a headphone design. The greater openness of metal mesh assists transparency of sound by reducing air resistance to the diaphragm’s motion, and the effect of reflections.

The problem of metal mesh is the size required to match the large ultra-thin diaphragms that can move enough air.

The reducing rigidity of larger meshes would reduce the accuracy of the sound. So to improve rigidity in the SR-Ω, the metal mesh was reinforced using an adhesive, in a manual operation requiring high-precision work. So tricky was this process that demand outstripped the ability to supply; it is thought that only 600 units of the SR-Ω were ever delivered. It took until 2011, with an investment injection from China’s Edifier when it took ownership of Stax, for the problem to be solved using a new multilayer metal-mesh construction, which became the basis for the SR-009 released in that same year.

That was further developed in the 2018 SR-009S, which refined the etching process to smooth the edges of the electrode openings, further reducing air resistance, while gold-plating the electrodes to both stiffen them and reduce their electric resistance. The results were stunning; the SR-009S, with the SRM-700S driver, went on to win the top Sound+Image headphone award.

New flagship

Now we have the new flagship, the SR-X9000. It raises the bar once more, beginning with a new version of that metal-mesh electrode system. The ‘MLER-2’ from the SR-009S has evolved into the four-layer ‘MLER-3’ (the ‘MLER’ stands for ‘Multi-Layer-Elect-Rords’ [sic]). The ultra-thin plastic film diaphragm has been increased in size by 20% over the SR-009S and this is flanked by a new and more rigid combination of metal-mesh electrode and a frame-like etching electrode which are bonded together using thermocompression.

In electrostatic designs, a bias voltage is applied to the ultra-thin diaphragm, which is sandwiched and suspended between two plates (called stators; Stax often calls them electrodes), to which the fluctuating voltage of the audio signal is applied as a push-pull signal where one side is always the reverse of the other. The diaphragm is attracted towards one stator, and ‘pushed’ the same way by the other. When the signal reverses, the diaphragm moves the other way. Thus its movements follow the audio signal, and because it has so little mass and the movements are quite small, there is little inertia to the movement, which allows electrostatic speakers to deliver their reputation for incredible detail and low distortion.

You need protective guard meshes outside the electrodes, but these can cause reflections which muddy the sound before it reaches the ear. On the SR-X9000 the guard meshes been redesigned to reduce reflections by using pillars of different heights at front and back to vary the gap between the sound unit and the guard mesh. With the guard mesh no longer directly parallel to the sound unit, Stax says that reflection effects are all but eliminated, thereby clarifying the sound.

This new construction still requires skilled manual labour at Stax’s Japanese headquarters, and as with the SR-Ω, we gather that demand is already outstripping the ability to make them. When we collected the review pair from Australian distributor Audio Marketing, together with the flagship SRM-T8000 driver unit, we heard that only three pairs of X9000s have yet made it to Australia, with a promise of more for Christmas.

One of the problems with the electrostatic approach is the relatively low strength of electrostatic fields compared with magnetism. Hence high voltages are required both for the bias voltage and the audio signals, to create fields sufficiently strong to move the diaphragm. In the beginning, Stax used voltages of around 200 volts to create its electrostatic fields, which worked, though limiting the volume available. The arrival of rock music changed listener’s expectations of loudness, and Stax responded by upping the voltages used to create the electrostatic fields to the 580V it uses today on most models.

Hence you can’t be plugging Stax’s earspeakers into the headphone socket of a portable device or even a hi-fi amplifier. They need a dedicated ‘driver’, sometimes called an energiser, or more prosaically a headphone amplifier. So you’ll often see Stax sold as packaged systems of earspeakers and driver.

The connection between the two is made by the company’s 5-pin ‘Pro’ plug connector, the sockets for which look very like valve connectors.

In use

Talking of valves, the Stax driver we were loaned, the SRM-T8000 (£4395, $6090, AU$8000), employs two small-signal 6922 valves in the input stage (hidden away under the substantial casing). These then drive a Class-A solid-state output stage. The T8000 is a substantial and solid unit some 32cm wide and nearly 40cm deep, offering three analogue inputs – two on unbalanced RCA and the third balanced on XLR sockets – and it has twin outputs so that you could, should you be so magnificently equipped, listen alongside a listener using a second pair Stax earspeakers.

The box for the SR-X9000 earspeakers is a beautiful case of dark paulownia wood, known in Japanese as kiri. This is a fast growing hard wood, light in weight, fine-grained, and warp-resistant, used in Japan for centuries for storage chests and boxes, as the wood keeps out humidity, heat and even insects. This box with its soft plush interior should keep your Stax earspeakers in perfect condition.

Lifting them out you can feel their fair weight, just over 430 grams and a little more once the cables are hanging, but as soon as you place them on your head and feel the real sheep leather around your ears (the surrounding areas are high-quality artificial leather), the comfort level is so high and their weight so well dissipated that they feel remarkably light; these are headphones that won’t ever discourage listening.

The main enclosures are machined aluminium; they hold the gold sound units firmly in place, clearly visible through the open guard meshes; it’s immediately clear that careful handling and avoidance of contact with those end meshes is important. Keep them in that paulownia box!

The two enclosures are connected by a stainless steel headband assembly – none of the plastic hinges which sometimes alarm on lesser Staxes. The headpad which contacts your hair – or head – is again made of real leather.

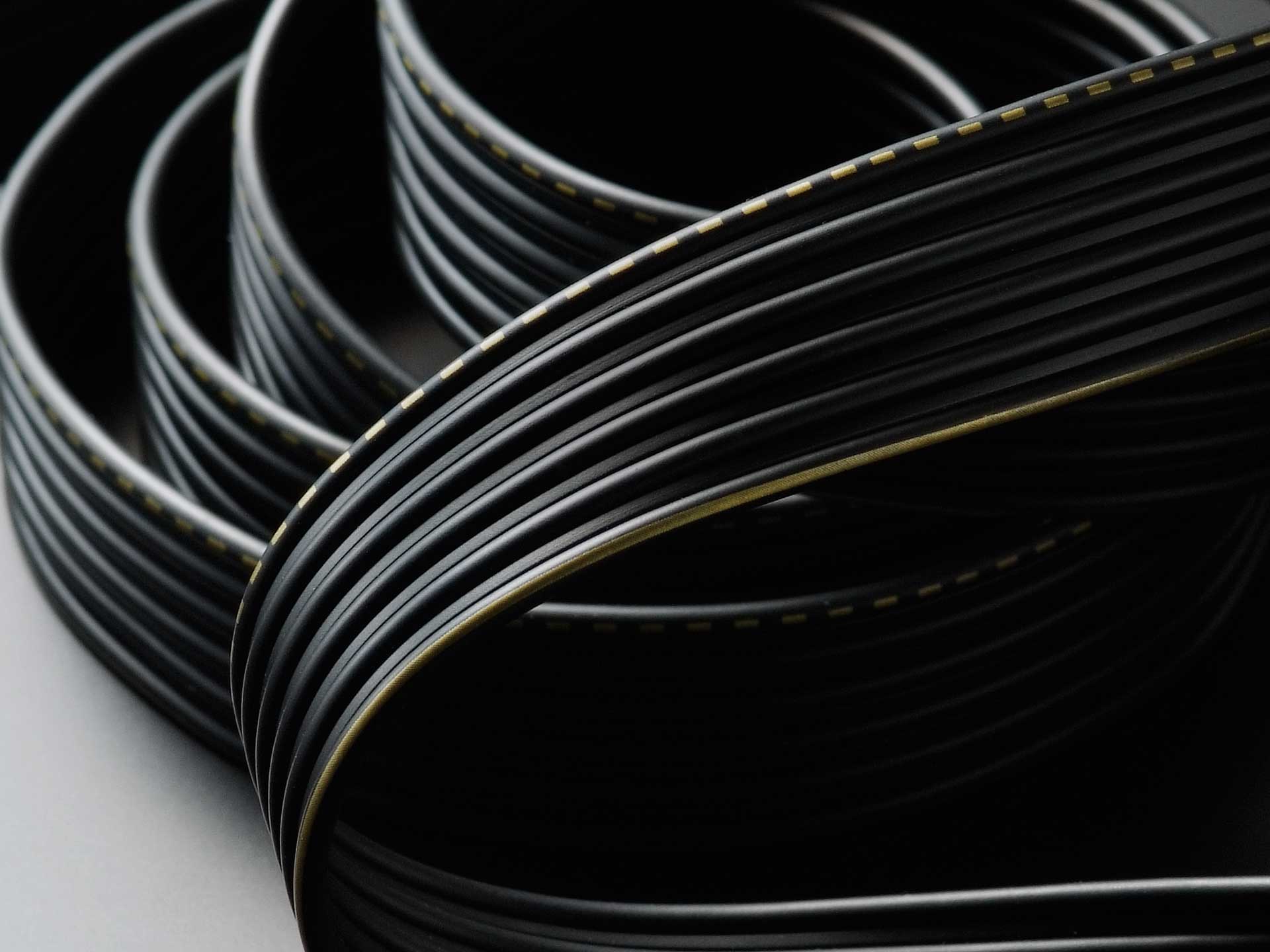

The final element is the cabling – one of those classic six-strand liquorice cables favoured by Stax, this one with 6N annealed copper (99.9999% purity). We love these liquorice cables not only for their appearance but because they’re completely silent if you move them, unlike many headphone cables. Even better, you get two of them in the box – 1.5-metre and 2.5-metre varieties – useful both for preferred use, and just for having a spare.

Classical music would have been the mainstay in the earliest days of Stax, so we began with that. The thrilling qualities of electrostatic performance were immediately apparent. Arvo Part’s Fratres For Eight Cellos (Naxos 1997) rises gradually from the softest sul tasto to full-strength ensemble in the middle, and such was the silence behind the Stax presentation that we set the intro higher than we otherwise might. The peaks were fully fledged indeed, yet distortion free and emotionally full.

The detail is extraordinary. Despite some stormy dynamics in Mozart’s ‘Jupiter’ symphony (Berlin Phil, 1970, a remarkably hiss-free recording on the Complete Karajan EMI recordings set, CD 64), you can hear the flop of flute keys and turns of sheet music pages. This is why classical fans are advised not to buy any headphones without first spending time under the spell of electrostatic detail and dynamics. It’s hard to stop listening.

Things remain similarly enthralling with acoustic jazz. It’s not just the accuracy of tone on Joe Henderson’s slightly off-centre solo sax on Ask Me Now (from Chesky’s ‘Ultimate Demonstration Disc’), it’s the sound of rapid taps on the keys, the way you sense his movement in the microphone field as he seeks to soften the sound.

This level of revelation might almost be expected from acoustic recordings, so it’s even more of an ear-opener to hear artificial fare given a full resurrection. The 2017 OMD track As We Open, So We Close is almost entirely electronica, and the speed and dynamics imparted by the Stax brought it all alive – from fizzy phat bass to creamy synth pads and an impeccably real vocal centre stage, just out of the spotlight within the wide soundstage created here.

Can they deliver the weight to drive rock and other modern genres? At first the bass, so natural with classical and jazz recordings, may feel light to those more used to closed-back headphones, especially the many designs which ‘push’ the lowest frequencies to set your head a-thrumm. But play Tyler, The Creator’s appropriately-titled EARFQUAKE though this Stax system and you surely won’t think them short of bass, and more, the ultra-thin diaphragm just about managed this huge bass content without masking the frequencies above. Meanwhile in the bass-free sections we’ve never heard this mix so clearly, nor the synths so pleasingly fizzy.

On The Flaming Lips’ A Spoonful Weighs A Ton, the crazy fuzz bass in the bridges lacked nothing for depth, and was tightly portrayed in the soundstage too, where many headphones splatter it everywhere. There were percussion details behind this bass that we’ve never noticed before because they’ve always been drowned or knocked unconscious by the more common dominant delivery. A bass sweep showed the low-end to stay at full strength to at least 60Hz, dropping away thereafter only gradually.

Also important, if auditioning, is to ensure the Stax you’re hearing is fully run in. The longer we ran them – and before critical listening they’d been playing continuously for 120 hours – the more the bass seemed to strengthen and solidify.

What the X9000s really love is a dense mix with plenty going on; they break down the detail so that it’s like watching a movie on IMAX – over here! over there! – you lock onto detail after detail. The wonderful ‘Like A Version’ take on Dumb Things by A.B.Original with Paul and Dan Kelly is one such, an outstanding live take with every piece perfectly in place. It saddens us that we may never hear it quite so clearly again.

Conclusion

We’ve never yet heard a Stax electrostatic earspeaker which hasn’t delighted us, so to hear the best-ever Stax earspeaker backed by the flagship driver was simply a transport to musical delight.

The combo delivered transparency, detail and soundstaging to shame even price-comparable dynamic designs, while the bass available was tight and real, never over-emphasised, and nearly always balanced enough to underpin even rock and modern artificial recordings, while given acoustic recordings they are simply unsurpassed.

Once under their spell, it’s very hard to stop listening; you want to hear more, more, more...

Postscript

Back on that blank tape assignment, this clarity from Stax not only gave me the confidence to rank those cassettes, it saved me during the subsequent saga of being challenged by the German makers of Agfa and BASF tapes. Their blanks had done less well than they clearly believed should have been the case, and they figured they’d caught us out because some star ratings were different between Agfa and BASF cassettes despite the tape inside being exactly the same formulation — aha!

But examining the ratings, it turned out that the sound quality ratings had indeed been the same, but the build quality ratings had differed, because the shells were different. ‘Aha’ right back at you, we said.

Not satisfied by this, they flew over from Germany to test my hearing, I kid you not. They suggested a challenge which they had been taking to hi-fi shows, where you listened to 20 short segments of audio, some from the input to a tape deck, some from the replay heads. Their tapes were so good, they said, that you couldn’t hear the difference, and at the hi-fi shows, anyone getting 14 or more out of 20 correct received a gift to take away.

In they came to the What Hi-FI? Hampton Road offices, and set up their tape machine. Could I use music of my choice, I asked? Yes, they said, so I selected a fairly quiet piece of Philip Glass. Could I use headphones of my choice, I asked? Yes, they said, so out came the Stax SR-Lambda Signature earspeakers and their driver. We plugged them up, and I waved them to start.

Through the Stax earspeakers, the hiss on the recorded tape was not very difficult to hear, and I remember also keeping mental time with the Philip Glass pulses to spot the time delay evident on the recorded segments. I scored 19 out of 20, and they left very quietly.

SPECIFICATIONS: Stax SR-X9000

Type: Push-pull open electrostatic circumaural headphones

Sound unit: Circular plastic biased diaphragm, MLER-3 stators

Frequency response: 5Hz–42,000Hz

Impedance: 145kΩ (including cable, at 10kHz)

Sound pressure sensitivity: 100dBSPL @ 1kHz

Bias voltage: DC580V

Earpads & headpad: Genuine leather in skin contact areas, high-quality artificial leather elsewhere

Cable: Silver-coated 6N (99.9999%) OFC parallel 6-strand wide, 2.5m & 1.5m

Weight: 432g (without cable)

Tested with: SRM-T8000 Vacuum Tube Input Driver Unit, $8000

Jez is the Editor of Sound+Image magazine, having inhabited that role since 2006, more or less a lustrum after departing his UK homeland to adopt an additional nationality under the more favourable climes and skies of Australia. Prior to his desertion he was Editor of the UK's Stuff magazine, and before that Editor of What Hi-Fi? magazine, and before that of the erstwhile Audiophile magazine and of Electronics Today International. He makes music as well as enjoying it, is alarmingly wedded to the notion that Led Zeppelin remains the highest point of rock'n'roll yet attained, though remains willing to assess modern pretenders. He lives in a modest shack on Sydney's Northern Beaches with his Canadian wife Deanna, a rescue greyhound called Jewels, and an assortment of changing wildlife under care. If you're seeking his articles by clicking this profile, you'll see far more of them by switching to the Australian version of WHF.