TV tech explained: our essential guide to buying a TV

The latest hi-fi, home cinema and tech news, reviews, buying advice and deals, direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

With today’s tellies now more feature-laden than ever, it can be a daunting prospect to try to find one that’s right for you. But you aren’t alone – the info below will help you navigate the minefield of TV tech, understand what to look for when you’re demoing sets in a shop, and even deflect the blind-you-with-jargon sales patter you might encounter…

Types of TV

There are three main types of set: LCD (which includes LED sets), plasma and OLED. This last one is very new, very rare and very expensive – so you’re unlikely to see many OLED tellies in shops for a few years.

LG's 47LW650T LCD uses passive 3D tech

LCD

Liquid Crystal Display. LCD sets are the most common type of TV, especially at sizes under 40in. Arguments rage about whether it’s worse in terms of contrast and colour than plasma tech, but over the past few years, it’s improved to the point where, on the best sets, you’d be hard-pressed to tell the difference.

A backlight shines through the coloured pixels to send the image into the room. LCD sets tend to be slim and light, making them better for mounting on flimsier walls than heavier plasma sets.

The latest hi-fi, home cinema and tech news, reviews, buying advice and deals, direct to your inbox.

Panasonic's TH-85VX200 plasma is a £42,000, 85in monster

Plasma

Plasma displays don’t have a backlight; instead, each pixel on the screen emits its own light. In the past, this has given plasma displays an advantage where contrast is concerned, since when a pixel is turned off, it’s completely black.

Conventional backlights in LCD sets continue to emit light, even if the pixels are turned off. Plasma displays are typically heavier and more expensive than their LCD counterparts – but if you prefer the picture, then go for it.

Plasma displays have faster response times than LCD, which will appeal to the gamers among you – though LCD is closing the gap here, too.

LG's 15EL9500 OLED TV is 15in, costs £1700

OLED

The technology is still in its infancy, so you won’t see it in shops unless you frequent the kind of places that offer a free private jet with every purchase, but OLED is an exciting development.

It uses a thin layer of organic molecules that emit light when a current is passed through them – and because it requires so little electricity and circuit bulk, the panels can be made incredibly thin (and are astonishingly cheap to run). Watch this space (or click here if you’re made of money).

If you have picture windows or a south-facing room, sets with reflective screens (which includes many plasmas) are probably best avoided – you might end up seeing more of your own reflection than the latest Homes Under the Hammer…

TV tech

Backlighting (conventional and LED)

Conventional LCD backlights are just that – a series of cold-cathode fluorescent lamps (CCFLs) placed behind an LCD panel. These shine light through the pixels on the screen (which would be nearly invisible without the light, as on a old-style digital watch), and thus make the image visible in the room.

The light level can be altered to dial-in detail to dark areas, but there’s an inevitable compromise in that turning it up also makes light areas lighter, and can result in a greyness to areas that should be inky black.

The solution to this has arrived in the form of LED backlighting. This comes in two types – edge-lit and full-array. Both use light-emitting diodes, which can respond more quickly and more accurately to brightness instructions, meaning quicker transitions from light to dark and back again.

Edge-lit sets have LEDs surrounding the display panel – their light is diffused across the back.

Full-array sets have LEDs placed directly behind the panel, which means the ones behind dark areas on screen can be turned off (giving deep, plasma-style blacks), while the ones behind light areas can be turned on for bright whites. This is called local dimming.

LED sets generally give much better punch and contrast than conventional backlights – and they use less power, too.

High Definition (1080i vs 1080p)

HD stands for high definition – and is expressed in terms such as 720p, 1080i and 1080p. The numbers indicate how many pixels there are on a screen, and the letter shows how it’s displayed on that screen.

The best quality of these, 1080p, is usually referred to as ‘Full HD’, while the others are called ‘HD Ready’. Don’t let anyone tell you that 720p or 1080i aren’t ‘proper’ HD, though. They are.

Here’s how it works. A TV picture is made up of horizontal and vertical lines of pixels. Ye olde cathode-ray sets in the UK display 576 lines – so a modern 1080p set is nearly double that, showing a widescreen picture composed of 1080 horizontal and 1920 vertical lines (you’ll see 1920 x 1080 on marketing blurb).

The ‘p’ stands for ‘progressive scan’, and tells you that each line of the picture is drawn sequentially – 1, 2, 3, 4 … 1078, 1079, 1080 – for each frame of video shown.

The ‘i’ stands for ‘interlaced’, and means that for each frame, the picture is rendered in two passes (even-numbered lines followed by odd-numbered lines). It’s still an HD picture, but might not look quite as smooth as the progressive version. A 720p set has 720 lines of picture (1280 x 720 pixels horizontally and vertically), drawn progressively. You won’t see 720i.

Even 720p pictures make a difference to what you see compared with standard definition: images have more detail and objects stand out from their backgrounds more clearly.

Broadcast HD is generally shown in 1080i format, because the ‘p’ version takes up too much capacity to be beamed through the air. Blu-ray discs almost always use the full-fat 1080p flavour.

3D (Active/passive)

The next big thing – but it requires some thought (and lots of demos) if you’re to find the right set for you. 3D televisions come in two flavours – active-shutter and passive, with active-shutter being the most common.

This system uses two separate full HD 1080p images, each showing a slightly different perspective and alternating hundreds of times per second.

You watch these images using battery-powered glasses that rapidly block out each eye in synchronization with the corresponding image being shown on the screen; we’re talking around 120 times per second.

Your brain puts these two different images together (exactly like it does with the different perspectives seen by your eyes) into a 3D picture.

Sony active-shutter 3D glasses

Active-shutter glasses like the Sony pair above are battery powered, and typically quite expensive (expect to pay around £100 per pair), but you do get a full HD image going to each eye – which comes into its own with compatible Blu-ray discs and some games.

Passive systems use simpler glasses (see below) with polarised filters in each lens, like in the cinema. In theory, this method can only display 1080i pictures rather than full 1080p HD quality, but the glasses are much cheaper and, some viewers say, more comfortable.

Passive 3D specs are much cheaper

Broadcast 3D TV (as opposed to Blu-ray discs) is shown in 1080i, too, so if this will make up most of your 3D viewing, this could be the system for you.

Whichever type of 3D TV you go for, it’s worth demoing it with everyone who’s likely to be watching it on a day-to-day basis.

Some people get on fine watching 3D on some sets, for example, while others find it tiring. Get a consensus opinion about which TV works for everyone, or you could end up having some monumental arguments at home…

Crosstalk

This is an issue that afflicts active-shutter systems to varying degrees. You’ll notice a slightly shimmery, unreal quality to the picture – perhaps some double edges, too.

Crosstalk happens when the synchronization between TV and glasses falters slightly, meaning images meant for your left eye go to the right one, and vice-versa.

Smart TVs give you access to the internet and apps

Smart TV

Buy a brand new telly and chances are it will let you connect to the internet, either via a wired ethernet connection or wi-fi (the latter is usually a cost option).

Each of the major manufacturers has its own take on the concept, but they all boil down to the same thing: your set essentially becomes a huge smartphone, flinging the door open on to a hoard of free content like you wouldn’t belive.

Not only can you access a wealth of catch-up TV services such as BBC iPlayer, ITV Player, 4oD and Demand Five, you can get to web services like YouTube, Facebook and Twitter.

Want more? You’ve got it. How about LoveFilm, Blinkbox and all manner of manufacturer-specific services that pull web content together based on your viewing habits?

And if you have a webcam (some tellies have them built in) and a Skype account, you can make free video calls – and never pay another phone bill again, if you so wish.

For the shutterbugs among you, a 2011 set will also display digital photos – either via USB or wireless transmission from your camera or phone, straight into the screen. You can also use a smart TV to play downloaded movies or camcorder footage, stream digital music from your computer and even play games without a console.

It isn’t as complicated to do as you might think, either. The likes of Sony, Panasonic, LG and Samsung all have dedicated remote-control buttons that take you to their app dashboards, while rival brands Philips, Toshiba and Sharp are developing similar systems.

Check before buying a new smart TV that it offers exactly the services you want. Content varies between brands.

Refresh rate

Refresh rate is the number of times per second that the picture is changed on the screen.

This is one of the numbers you’ll see plastered all over advertising and literature – it screams figures like 50Hz, 100Hz, 200Hz, and even 600Hz in some cases. Beware the low numbers (they aren’t up to snuff), and ignore the high numbers above 200Hz (they’re largely just marketing hype).

The sweet-zone is 100Hz-200Hz. Essentially, it means the footage, broadcast at 30 frames per second (or 24 frames per second in the case of many Blu-ray discs; the speed at which film is shot), is updated between 100 and 200 times per second on the screen – making for smoother motion and less blurriness in fast-panning scenes.

To use it, you have to switch on the motion-processing modes (see below).

Motion processing

Since it’s impossible to add detail to footage where it doesn’t exist, motion-processing tech performs clever tricks involving frame duplication to create hundreds more artificial frames per second.

So each of the 24 frames per second on a Blu-ray gets shown, say, 200 times per second on the display.

That definitely smooths things out, but there is a downside. Heavy motion processing can make the picture look very unnatural – motion becomes too smooth, and lighting effects get butchered. Imagine how a 1970s Doctor Who episode looked, and you might get a better idea.

Luckily, you can dial-in the amount of processing you want – or switch it off altogether. Try all the modes out in the shop.

As an artistic aside, though, consider that if a film director shot his movie at 24 frames per second, he meant it to be watched at 24 frames per second – not 600…

HDMI

High Definition Multimedia Interface is the Scart cable for the digital age (see above): a high-quality digital video/audio connection from source components to displays. Have a look at where the socket is located on the set – is it on the side or the bottom? This could affect whether or not you want to put your TV on the wall.

Broadcast telly

Analogue TV

From next year, this will cease to be relevant, since the UK is switching to a digital-only TV-broadcasting system by 2012. For now, though, analogue consists of BBC One, BBC Two, ITV, Channel 4 and Channel 5. And Teletext, such as it is.

The analogue TV signal is slowly being switched off around the country as individual regions make the move to digital.

Freeview/Freeview HD/Freesat

For most of us, though, digital is where it’s at. Offering an increasing number of TV channels and radio stations (as well as red-button services), digital TV is available on all new TV sets. To check whether you can receive it, visit www.freeview.co.uk/availability.

There are three versions:

Freeview is the most basic format – and, as you might gather from the name, doesn’t cost a penny to watch. It’s broadcast in standard-definition, and has up to 50 TV and 24 radio stations.

Freeview HD is, again, free. Despite the name, however, it isn’t all shown in high definition – just BBC HD, BBC One HD, ITV1 HD, and 4HD. These channels are broadcast in 1080i format, and really do look a cut above the regular standard-def offerings. It’s currently available in 77 per cent of UK homes.

Freesat is another free service, independent of Freeview. If your house has a satellite dish (even one left by a previous occupant will work if it’s still connected to the socket in your living room), you can get similar channels to Freeview HD – including the high-def ones listed above.

We think the quality is generally slightly better, too – and it’s your only choice for free HD TV if you live in one of the 23 per cent of homes that can’t receive Freeview HD.

Some TVs offer all three of these, others only a couple. It’s worth checking before you buy, because Freesat is available almost everywhere in the UK, while Freeview and Freeview HD coverage can be patchy.

Freeview, Freeview HD and Freesat set-top boxes are also available separately.

EPG

You use the Electronic Programme Guide to plan viewing, record programmes, get plot synopses and select channels to watch. Since you’ll be spending a lot of time using it, try it out in the shop – some are more intuitive than others.

What to look for in the shop

Size

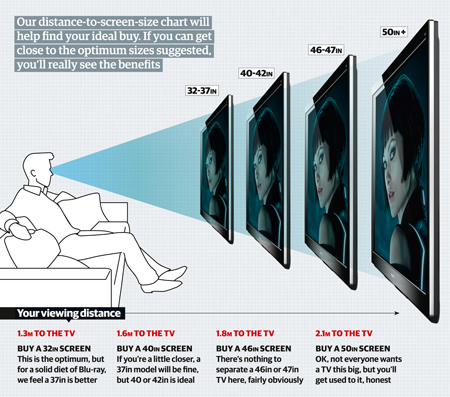

If this is your first foray into buying a big telly, don’t worry. You’ll be surprised at how quickly you get used to the size. With modern sets showing high-resolution, high-definition pictures, you can sit a lot closer to them than you could with old-style CRT TVs.

The closer you sit to a larger set, the better it will look if you feed it an HD-heavy diet; standard-definition content can look quite nasty when viewed up-close on a large flatscreen display.

Before you buy, measure the distance between your seat (where your head is, not the front of the sofa) and the screen of your existing TV. Check the chart below to find the right screen size for your viewing distance.

Stand at the various distances in front of the demo sets and you’ll be surprised at how close you can get before things get uncomfortable.

Contrast

The amount of variation between black and white levels. Low contrast used to be a problem with flatscreen displays, but on the whole, most modern sets are strong in this area – plasmas more than LCDs, although LCD sets with LED backlighting (see above) offer a more able variation on the theme. A lack of contrast can mask detail in darker areas.

You’ll see a lot of laughably huge numbers being bandied around – 100,000:1, 5,000,000:1 and so on, but take them with a pinch of salt (our favourite claim is “infinite” contrast). Your eyes are the best judge. Play with the controls in the shop. Can you see detail in really dark areas, while keeping the whites nice and clean? Then you’re on to a winner.

Picture modes

Most TVs now offer various options to tweak colour balance and contrast, allow the screen to alter itself automatically depending on what it’s showing, and so on. Our advice is to turn all that off in the shop and then switch it back on one mode at a time so you can see the effect it has. We tend to leave most switched off when all’s said and done.

Noise

We’re talking about picture noise here, not audio crackles. If you see unpleasant snow, specks, pops and flashes in the picture you’re taking a look at, walk away.

Pixellation

A loss of definition leading to visible blocks of pixels during fast-moving scenes, such as seen when watching sports in standard definition. The problem is less common nowadays, but it’s still seen when the TV can’t keep up with the source signal, or if the broadcast is of low quality.

Edge definition

Imagine watching Liverpool playing football on TV. The players, in their red strips, should stand out in sharp relief from the green of the pitch. Bad edge definition will manifest itself in pixellation around the players, maybe some blurring and haloing and a general ‘wooliness’ to the picture.

Motion

Does it look smooth? In fast-panning scenes, does the TV struggle to keep up with the camera? If so, you’ll see a judder to the picture. In sport, you might see a bit of blurring. High-definition pictures are usually a lot better in this regard.

Colour

How natural is it? Do skin tones actually look like skin? And if they do, how does the rest of the TV’s colour palette stack up? It’s no good having perfect skin tones if the rest of the picture is washed-out and bland. Check to see if blue skies are actually blue, green grass doesn’t have a cast to it, and that white areas are truly white.

USB sockets

These let you expand your TV’s functionality with optional wi-fi (if it doesn’t already have it built in), and play media such as music, photos and video files from memory sticks.

Wi-fi and other network connections

If a TV has wi-fi built in, you can connect it to your home wireless network and then access smart TV services (and even other supported devices on your network, such as hard-drives and computers) with a minimum of hassle. Some manufacturers insist you buy an optional USB dongle to enable this functionality.

Alternatively, you can plug your set into your network router using an ethernet cable. This generally proves more stable for data-heavy tasks such as streaming video.

If your router is in a different room to your TV and you don’t want to run huge lengths of ethernet cable around your house, consider using a home-plug system, which uses your mains-circuit wires to transfer data.

What does it come with?

Wall-mounting bracket

Do you get a bracket to mount the TV to the wall? If not, and you want to do that when you get home, you’ll need to factor in the extra cost.

Free delivery and old-set pickup

Some companies will deliver your set (and take your old one away) free of charge. It’s worth asking…

Extra 3D glasses

Try to get extra glasses thrown in with the set. Some come with only one pair, which is pretty useless if you have a family of five. If you buy them separately, you could end up spending hundreds of pounds – though that’s just for active glasses. Pairs of passive specs cost only a few quid each.

HDMI leads and other cables

If your TV comes with an HDMI cable, it will probably be a bargain-basement one. It’s worth upgrading it straight away – some shops might have deals on for bundled upgrade cables, so check when you’re demoing the sets.

Extended warranties

Some stores offer five-year warranties as standard with certain sets. If you’re the sort of buyer who likes added peace of mind (without having to pay for it), shop around.

After-sales service

Does the retailer offer additional services? Some will calibrate your new set to deliver the best possible picture quality, for example. It’s worth factoring in these elements when considering where you buy from.

Andy is Global Brand Director of What Hi-Fi? and has been a technology journalist for 30 years. During that time he has covered everything from VHS and Betamax, MiniDisc and DCC to CDi, Laserdisc and 3D TV, and any number of other formats that have come and gone. He loves nothing better than a good old format war. Andy edited several hi-fi and home cinema magazines before relaunching whathifi.com in 2008 and helping turn it into the global success it is today. When not listening to music or watching TV, he spends far too much of his time reading about cars he can't afford to buy.