What made the original NAD 3020 budget amplifier such a legend?

We talk to engineer Taresh Vadgama, who has spent over 40 years with NAD, and take a deep dive into the legendary budget amplifier's design

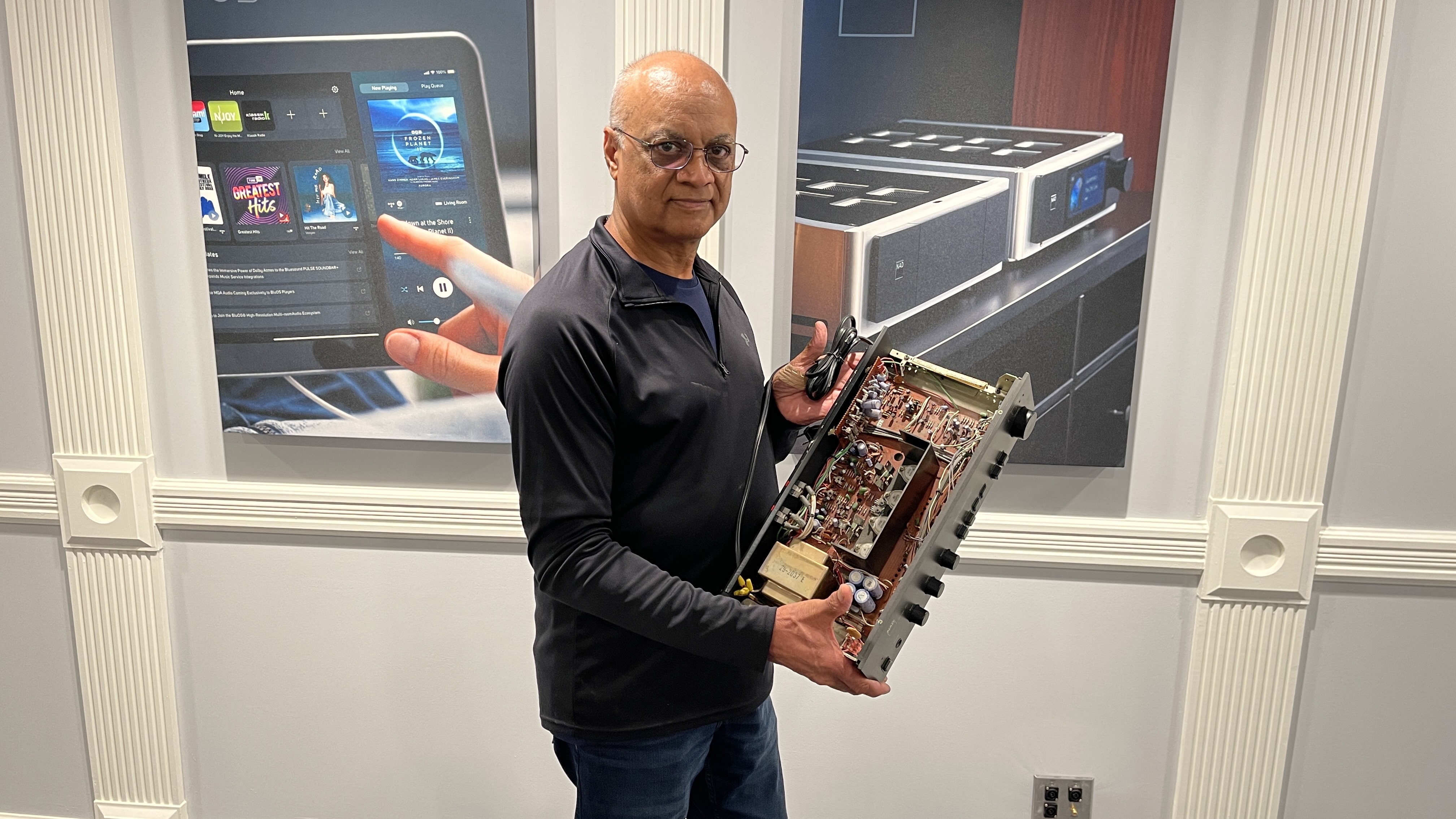

Taresh Vadgama joined NAD as an engineer back in 1984 and has worked at the brand ever since. He is currently parent company Lenbrook’s Vice President of Development and Manufacturing and, as such, is right at the core of product development for brands such as NAD and Bluesound.

Given that Taresh started working at NAD when production of the original 3020 integrated amplifier was in full swing, I took the chance to have a deep dive into the background of the landmark budget integrated amp when I met him at Lenbrook's HQ in Canada.

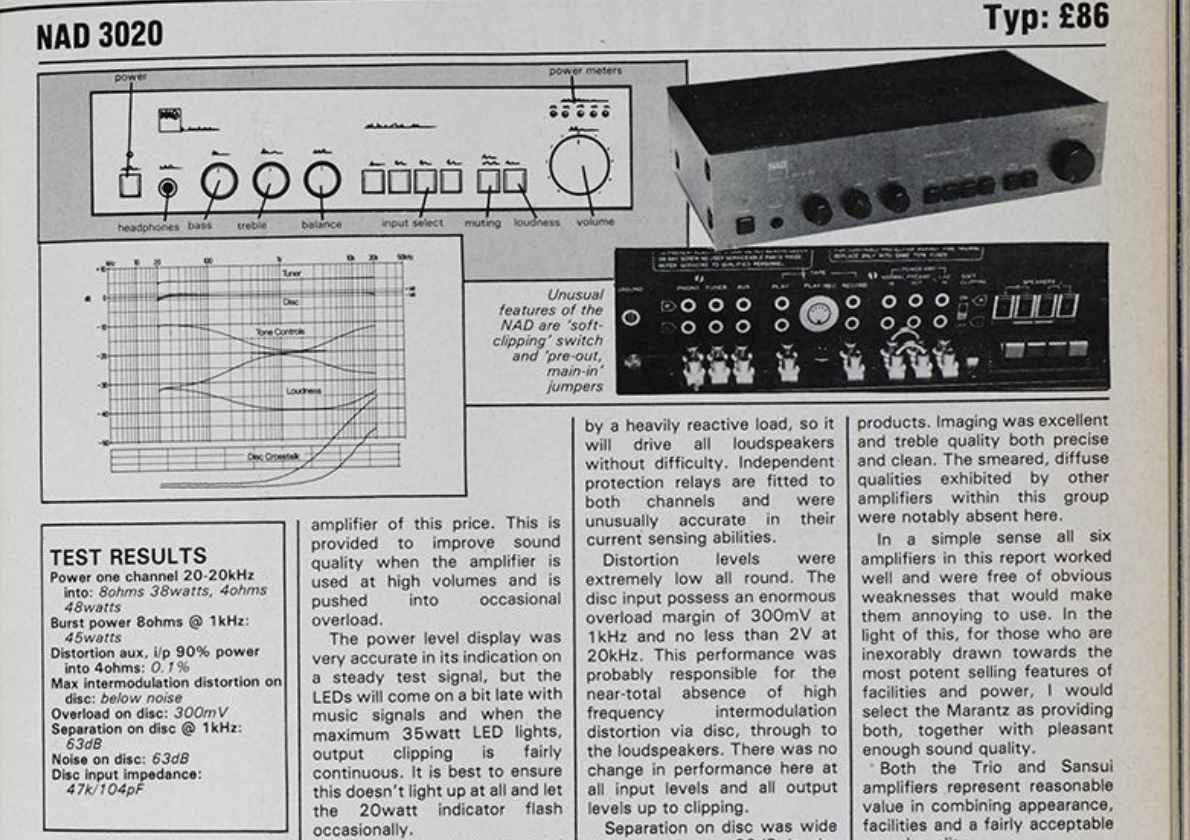

Launched in 1979, the legendary NAD 3020 stereo amp cost just £71 and single-handedly established the fledgling New Acoustic Dimension (NAD) brand as a serious player in the hi-fi/audio market. It is widely claimed to be the best-selling integrated amplifier ever.

WHF: You started working at NAD in 1984. What was the company like back then?

TV: It was fun and exciting. I was employee number three in the lab. NAD (New Acoustic Dimension) was located in Finchley, London. Bjørn-Erik Edvardsen was the first employee on the engineering side. He was responsible for the original 3020’s design, and there was another engineer called Peter Bath. They were both ex-Dolby people – and I was the exception.

At the time, the company employed around 15 to 20 people, including Martin Borish (who founded the company). NAD’s manufacturing model was unique for the time, where everything was made using contract manufacturers. The brand didn’t own any of the factories that made its products. This method of working is the norm now, but it wasn’t back then.

What do you think made the 3020 a success?

The latest hi-fi, home cinema and tech news, reviews, buying advice and deals, direct to your inbox.

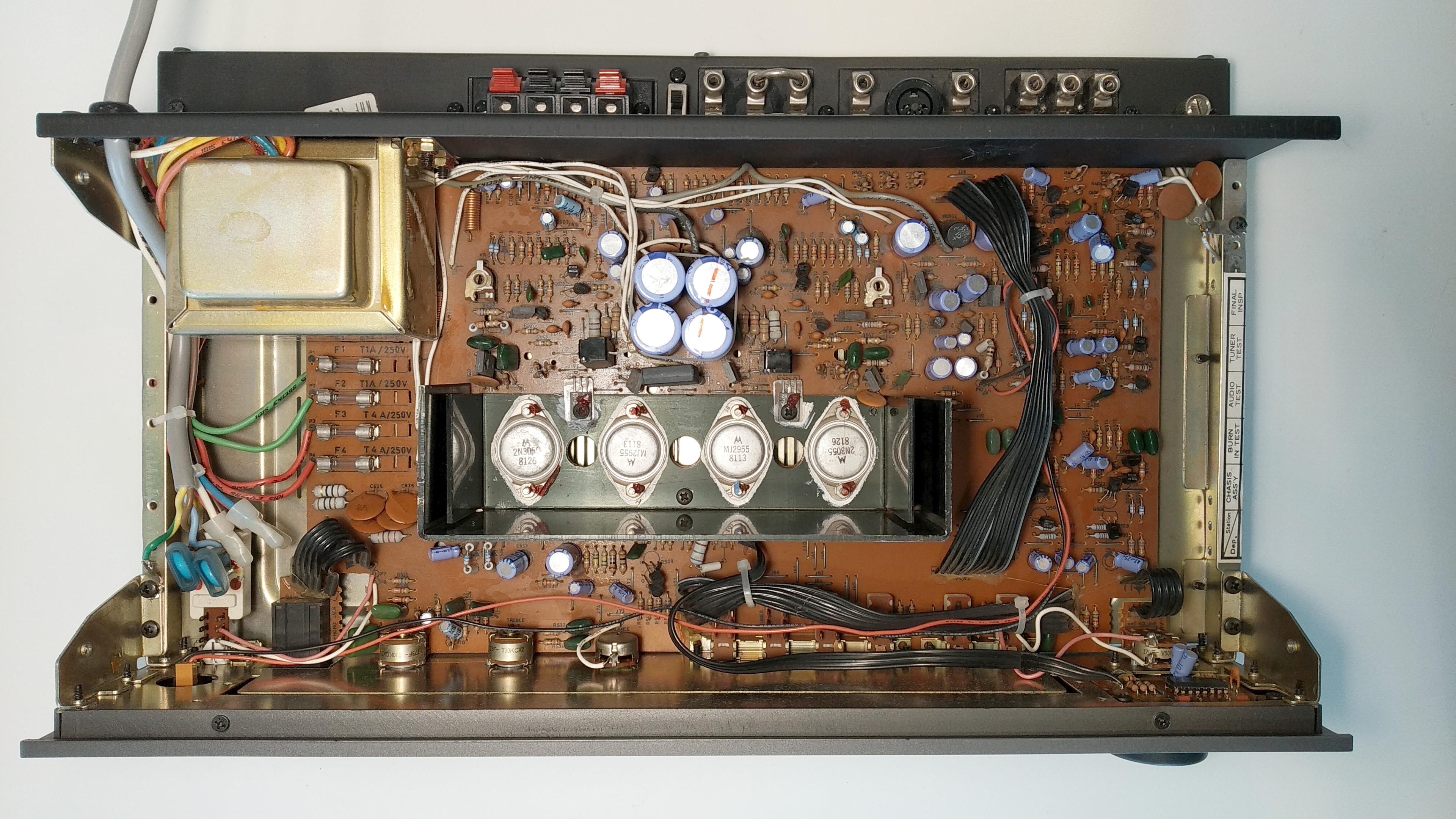

The 3020 was affordable, well-equipped and had a brilliant performance for the time. Erik wanted to keep things simple. The circuit used relatively low levels of feedback; just the right amount to keep the amplifier stable without overdoing things.

He looked at the mass-market Japanese amplifiers of the day and, while they had high claimed power outputs under lab conditions, they had difficulties driving real speakers with reactive loads.

Erik realised early on that driving real speaker loads required plenty of current, and that came down to the quality of the power supply and design of the output stage. This is something we prioritise to this day. Any amplifier we make has to be capable of high levels of output current, so if you have a very difficult reactive load, it will have no difficulty driving it.

The 3020 also had a really quiet input stage and a great low-noise phono section. With the phono stage, Erik’s philosophy, something we continue to this day, was to ensure it had a really good signal-to-noise ratio.

In this kind of circuit, you want to keep the input noise as low as you can. It’s a high-gain stage, around 60dB, so any noise on the input gets multiplied by around 1000 times. Next is the overload. It has, I believe, 20 dB of overload, so you can put a higher signal in and it won’t clip. This is something that helps when dealing with high-level transients.

The amplifier had links on the back panel that connected the preamp stage to the power amplifier. This made it easy to upgrade to a bigger, higher-output power amplifier.

Early 3020s had all the inputs facing upwards on a ledge. That was originally done to simplify the layout so you could use just one PCB, which helps with ease of assembly. Once you put the connections vertically on the back panel, you add an extra stage in construction linking the connectors to the main circuit board, which adds more cost.

However, later on, we switched to a more conventional placement as customers asked for it. Also, putting all the connections on the back panel provides more space, allowing the addition of more inputs if required.

How did the 3020 develop over time?

There was a more purist version of the amplifier called the 3120, which got rid of the tone controls to give a purer signal path. Tone controls in the zero position don’t really do anything, but they can add noise into the signal path. This was done in response to the competition that was getting more purist in nature.

We also made the 1020 preamp and a matching power amplifier. These were essentially the 3020 circuit split into two. The pre/power performed better because it freed the preamp from dealing with the high currents in the power amplifier section, and you end up with a really low-noise stage. Each part now also has its own dedicated power supply.

We had the chance to try out a fully-functioning sample of the original NAD 3020 a few years back, and found ourselves having a thoroughly enjoyable time listening to it in our test rooms.

We said in our feature: "No product is perfect, and expecting that from a 40-year old budget design isn’t realistic. However, we are utterly charmed by the 3020. Our test room is packed with excellent, far more capable alternatives, yet we carry on listening to the little NAD way longer than we need to.

We love its enthusiasm and the way it encourages us to play just one more track. That’s the true mark of greatness, and make no mistake, the NAD 3020 belongs up there with the very best the industry has ever made."

MORE:

Read the full retrospective feature here: That Was Then... NAD 3020 amplifier

Read our review of the modern NAD D 3020 V2

Ketan Bharadia is the Technical Editor of What Hi-Fi? He has been reviewing hi-fi, TV and home cinema equipment for almost three decades and has covered thousands of products over that time. Ketan works across the What Hi-Fi? brand including the website and magazine. His background is based in electronic and mechanical engineering.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.