From college-room creations to British hi-fi icons, Arcam’s John Dawson reflects on 50 proud years of electronics engineering

And his run is far from over

The latest hi-fi, home cinema and tech news, reviews, buying advice and deals, direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

“I would go so far as to say that the SA45 is the best example yet of how far we have come,” says Arcam’s John Dawson of the company’s flagship streaming amplifier, which arrived earlier this year and is the big brother of the newly crowned What Hi-Fi? Award-winning SA35. That’s some statement considering the rich heritage of the British company that turns 50 next year.

Indeed, it was back in 1976 when A&R (Amplification and Recording), as it was initially called, released its first product, the A60 stereo amplifier – some years after John had begun producing sound effects for college theatrical societies, and building amplifiers in his college room for his fellow Cambridge University students’ discos.

He and fellow co-founder, the late Chris Evans, met at the university’s Tape Recording Society (CUTRS), which gave the duo a platform to interview audio industry professionals. Coincidentally, Ray Dolby, a then-27 doctoral candidate at the uni’s Pembroke College, was a senior member. “CUTRS is what formed me,” says John. “It helped me get into the trade.”

Chris and John were in the middle of completing PhDs when A60 development took over… neither of them finished writing theirs up!

It marked the transition from college hobby and a flirtation with audio electronic design consultancy to ‘let’s see if we can take a product all the way from design to small-scale manufacturing’. And, as is evident from the business’s formalisation just a few years later and the success of its subsequent four decades, they jolly well managed it.

Ahead of Arcam’s 50th birthday next year, John looks back on half a dozen milestones in his career thus far – the first, unsurprisingly, being the one that started it all.

1. Arcam A60: the amplifier that broke out of Cambridge University

“It was designed to be both reliable and to sound as good as possible for a reasonable price – more expensive than the standard Japanese products but much less than the British pre/power amplifier combinations from the likes of Quad and Naim,” says John. He and Chris planned to build 50 of them to sell to their friends around the uni.

The latest hi-fi, home cinema and tech news, reviews, buying advice and deals, direct to your inbox.

So off they went, placing all major components on a single fibreglass PCB with almost no wiring, adding a toroidal power transformer and housing it within a wooden-topped chassis, with a steel base plate and stock aluminium extrusions for the front and rear panels.

The initially priced £99.50 (ex VAT) amplifier soon broke out beyond the Cambridge University walls, and before its creators knew it was driving Rega turntables and small British loudspeakers.

“John Greenbank, who ran the speaker maker Tangent Acoustics, recommended we talk to the UK trade, and a handful of dealers subsequently took on the A60,” he remembers.

“We had submitted an early A60 for a technical review in Practical Hi-Fi magazine (written by Noel Keywood under a pen name), and when the very positive report came out in early 1977, it really put us on the map, convincing a lot more dealers to stock it.”

10 years and 32,000 sales later, it was time for the A60 to hang up its boots. The perfect debut? Pretty much. “From today's viewpoint, I would change almost nothing, except perhaps to substitute the fuse protection in the speaker outputs for a self-resetting mechanism, for both user convenience and performance,” says John.

2. Delta 70: the first UK-designed and manufactured single-box CD player

While amplifiers are still very much Arcam’s speciality today, spanning stereo integrated, streaming-inclusive, dedicated power, and AV surround sound applications, the company’s source electronics haven’t exactly walked in their shadows, having been a major part of the offering from the off.

Following the T21 tuner, which launched just after the A60, came the Delta 70 CD player in early 1987, the UK’s first totally designed and manufactured one-box CD player.

By that point, A&R Cambridge was still the trading name, but ‘Arcam’ had become the brand one. After Chris had left in 1985, John and the company’s financial director, Jacky Cross, refinanced the company with a second mortgage and sold a minority stake to a BES (Business Expansion Scheme). They used some of the funds to buy a $25,000 CD player manufacturing licence from Philips and start a ground-up design for a CD player using Philips parts.

“The standard designs of the day used a 14-bit chipset, but we went with the upcoming 16-bit chipset, which included the TDA1541A DAC and a digital (S/PDIF) output,” recalls John.

“We did all the right things in terms of isolated power supplies and proper analogue stages, etc, and it addressed some of the (partly justified) negativity about the sound quality of early CD in the press and trade, especially from certain turntable manufacturers. I like to say it was the first CD player Linn dealers felt they could sell with a clear conscience!”

3. Delta Black Box: the outboard DAC ahead of its time

Despite the Compact Disc receiving early criticism (some considered their digital sound a little ‘harsh’, which wasn’t helped by the somewhat forward high-frequency nature of some hi-fi speakers at that time), the format wasn’t backing down, and by the mid ‘80s the first mass-market players from Sony and Philips with digital outputs came to fruition.

John and Arcam’s head of engineering, Mike Martinell, had an idea: to create an outboard DAC/processor that would connect to a CD player’s S/PDIF output to improve sound quality. Niche? Yes. Bold? Absolutely.

“Both Sony and Philips offered these separate DACs for their flagship players, but at £800 a piece! So we saw a market opportunity,” says John. “The problem for us was that there was no way to translate the S/PDIF stream into the I2S signals needed by the TD1541A DAC without using lots of glue logic (digital housekeeping circuitry). This would take up a great deal of space and didn't suit our manufacturing methods.”

Good fortune saved the day, when an old university pal of John visited Arcam to have a product serviced. It turned out he was the product manager at Newmarket Microcircuits, a local manufacturer of custom integrated circuits (ICs) for the Ministry of Defence.

“12 weeks and £10,000 later, we had a working S/PDIF receiver chip in our hands that used a customised 1000-gate array IC made in the UK!” says John. “It wasn't cheap, at £10 per chip, but it still enabled us to design the world's first affordable [£250] outboard DAC. It made almost any CD player with a digital output sound better and, gaining favourable publicity for Arcam, really helped put the brand on the global map.”

Arcam developed more versions, including bitstream ones and a premium model that housed a master clock to feed back to a CD transport (eliminating jitter). But, as John proudly notes, “nothing quite surpassed the buzz of developing that initial unit”.

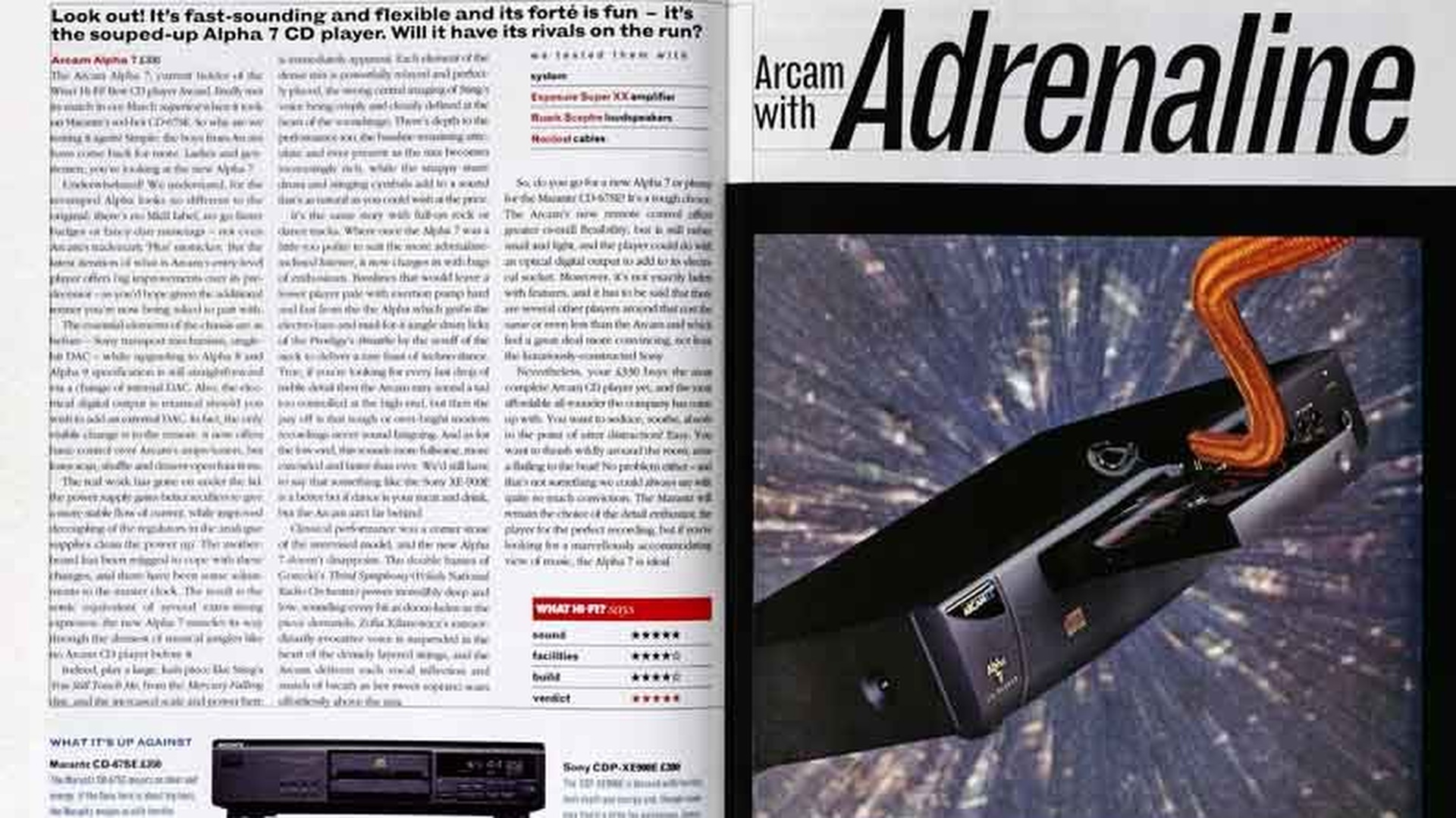

4. Alpha 7/8/9: CD players born from another case of serendipity

By the mid-1990s, Arcam knew itself: it had a series of mass-market and higher-end amplifiers and CD players, had broken into the AV space with a TV tuner and AV amplifier, had grown to more than 100 people, and was accumulating more than £10 million in annual sales. The Alpha CD player design was modular, with the option of upgrading the basic Alpha 7 player with better DAC boards to make Alpha 8 and 8SE models.

Cambridge was a ‘happening’ place in the audio world – just five miles from Arcam was dCS (Data Conversion Systems), which had spun out of Cambridge Consultants, and was redeploying technology originally developed for radar systems in military fighter jets.

The new firm was now making cutting-edge 24-bit/96kHz ADCs and DACs for recording studios, utilising high-tech stuff such as DSPs, FPGAs (field programmable logic arrays) and all-discrete multi-bit DACs. Arcam introduced itself.

“We got talking to them and wondered if some of this wonder technology might be foldable into an IC,” says John. “This might lower dCS's costs for more affordable multi-channel DACs and could also be used by Arcam for a state-of-the-art CD player, with the possibility of using it later in DVD players.

“We reached an agreement whereby Arcam would fully fund DCS to design a two-channel IC, which we could then put into volume production without additional royalties. dCS used a multi-project wafer process to develop the first 24-bit DAC samples and keep the project affordable.”

Arcam still needed an FPGA, but John explains they were able to replace dCS’s expensive DSP filtering with an off-the-shelf filter from Pacific Microsonics. Fitting the whole thing onto one four-layer PCB that could fit into the Alpha 7’s chassis was also a considerable effort, and the added per-unit cost of the PCB alone was £100; but the result was, John believes, well worth it.

“The Alpha 9's sound quality was class-leading, with incredible detail and none of the harshness often found in CD replay,” he says. “The IC only ceased production when the fabricator decided it didn't want to serve small customers anymore and tripled the cost!”

If John knew then what he does now…

Indeed, the technology found its way into the company’s forthcoming, higher-end FMJ products. They packed similar internal electronics as the Alpha, but into a luxury, heavy metal casework that would overcome the Alpha’s shortcoming: disappointing build quality.

And this ties in to what today’s John would tell student John if he could rewind the clock: “Don’t be afraid to put the price up!”

“We have never wanted to overcharge, but we learned that getting that compromise [between performance, design and value] right is very important,” says John, who learned that the hard way with the original Alpha amplifier back in 1984. For this affordable amplifier, the company employed industrial designers, who produced a nicely sculpted, 400mm-wide dark-grey front panel – but one that was ultimately plastic and uncoloured.

“It was an ‘objection to buying’ and never really accepted,” says John. When, after Chris’s departure from the company, he and Jacky Cross (“the backbone of the company who organised us all”), refinanced the company, a priority was to crack the Alpha unit. It needed colour, and it needed to grow from 400mm to proper ‘full-width’ (430mm) dimensions.

“There’s a garage down the road; I’m going to get a can of black spray paint and do it myself,” John said after being met with initial resistance from the staff. In the subsequent, slightly pricier Alpha+ (black) and Alpha 2 (black and 430mm) guises, sales picked up; Arcam sold 50 per cent more Alphas after each update.

DVD players: a proud project… while it lasted

“I am especially proud of the results we obtained with the DVD format”, says John, who at that time, just before the turn of the millennium, was effectively Arcam’s CTO (chief technology officer).

Its first DVD was to be developed alongside a whole product-spanning range of ‘2000 Series’ electronics, and was facilitated by a relationship with Zoran, a Silicon Valley tech company that made DVD processing chips, and whose software and hardware development Arcam contributed to over three chip generations.

“We built all our DVD players in the UK and were early adopters of progressive scan, DVD Audio and HDMI,” says John. “I was able to persuade them [Zoran] to include SACD replay in the final generation, and in my opinion, the Arcam FMJ DV139 universal player is as good as it gets for both audio and video. I still use mine today, not least as a CD player.”

Indeed, CD playback was the fallback for DVD players when they laid down their armour during the Blu-ray/HDVD format battle. “You couldn't give the DVD players away!” says John after DVD had nosedived into the pit of antiquated technology. Fortunately, Arcam was able to recycle the remaining stocks of parts by disabling the DVD functionality and repurposing the design as a CD37 CD/SACD player.

Class G amplification: the class that lasts

In 2008, What Hi-Fi? announced the arrival of the AVR600 as a “new megareceiver” and the company’s “most ambitious” home cinema amplifier yet.

The project had begun a few years earlier, and John’s contribution to the in-house design of this seven-channel amp revolved around the brief to make it sound as good as a comparably priced stereo model, and deliver 100 watts per channel into eight ohms while also driving sub-four-ohm loads properly.

Thus began the company’s long, renowned and celebrated relationship with Class G amplification. The technology is still, in continually developed form, used in the topology of many of Arcam’s AV and stereo amplifiers today, including the integrated A25+, surround sound AVR31 and aforementioned streaming-savvy SA35 and SA45.

“The biggest issue was simply to get the heat out of the box,” John explains. “Class D (switching) amplifiers ran cool, but were simply not good enough in terms of sound quality. We knew we would need to employ the same sort of Class A/B amplification as our stereo products, but with seven channels instead of two. The problem was obvious!”

John recognised that many high-powered professional amplifiers for gigs used more than one set of power-supply rails – a lower voltage one was employed for most signals, while higher voltage ones were engaged only when needed for musical peaks. The result is lots of output with low levels of distortion, without as much wasted heat energy and the matching thirst for electricity that Class A/B has.

Essentially, the design runs cooler and you can get more power out of box. It’s how Arcam’s Class G A25/35 can be rated at 120 watts, whereas John sweated just to get an 80-watt rating out of the Class A/B-running A15 in the same-sized chassis.

This ‘Class G’ amplifier circuit was first used in hi-fi by Hitachi in the 1970s. But, as John explains, it fell out of favour as a) the semiconductors needed weren't particularly good at the time, and b), perhaps more significantly, it was pretty expensive to implement.

“You can stick with transformer size [for Class G], but you have to have a whole extra set of power stages with all the bulk storage capacitors associated with that, plus an extra set of power transistors,” John explains. “If you do that with, typically, one set of these per channel, it gets quite expensive.

“I spent over a year in basic research and trials and was able to come up with my cost-effective, sneaky trick that used ‘lifters’ – Arcam's term for the power circuits that control the voltages fed to the output transistors – shared between several channels. It worked particularly well for AV receivers. The reality is you don’t need all the channels all the time, so it works out alright.

“I was also able to design an output stage with a biasing scheme that effectively eliminated the unpleasant-sounding crossover distortion associated with conventional Class AB amplifiers. This design behaves, measures and sounds like a Class A amp for the first 10 watts of output without the design’s associated power consumption and heat. When combined with Class G, the power amps are also able to deliver much more current into a loudspeaker than a conventional amplifier.”

For someone who failed to complete his PhD and has, in his words, “never had a proper job”, John Dawson has rather a lot to show for his contributions to global, never mind British, hi-fi. It’s little wonder he has been one of the few recipients of our Outstanding Contribution Award.

With John now a consultant to Arcam through his own consultancy company, perhaps his next career challenge will be defined by the brand turning the big five-o next year. Either way, the passionate 75-year-old parkrunner already has his next personal one: to run a half-marathon under two hours.

MORE:

11 of the best Arcam products of all time

Arcam co-founder John Dawson wins our Outstanding Contribution 2023 Award

Streaming hi-fi systems from Arcam, NAD, and Ruark make their mark at the What Hi-Fi? Awards 2025

Becky is a hi-fi, AV and technology journalist, formerly the Managing Editor at What Hi-Fi? and Editor of Australian Hi-Fi and Audio Esoterica magazines. With over twelve years of journalism experience in the hi-fi industry, she has reviewed all manner of audio gear, from budget amplifiers to high-end speakers, and particularly specialises in headphones and head-fi devices.

In her spare time, Becky can often be found running, watching Liverpool FC and horror movies, and hunting for gluten-free cake.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.