AI sound is here – and I urge you to demo it

You've tried the chat, you've seen the art - now hear the AI music

The latest hi-fi, home cinema and tech news, reviews, buying advice and deals, direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Only last issue in the print magazine of Sound+Image, I was writing about AI text-to-image, which is such fun: ask for “a hi-fi turntable in the style of a da Vinci codex” and you receive magnificent art in return (above), at the risk of enraging everyone remotely artistic.

I jested in that issue that soon music services will be similarly AI-enabled, and we will ask (by voice, of course, nothing so 20th-century as a keyboard) for “Nick Cave songs in the style of Abba”, or indeed Abba songs in the style of Nick Cave if you like, and presto, Loverman a là Chiquitita.

‘Oh what fun we will have’, I wrote, ‘what law-suits we will see’. What a riposte Mr Red Hand Himself would unleash upon the world if his vocal style and band were mimicked, rather than merely his poetry. (He recently tore into some lyrics sent to him that were composed by AI in the style of Nick Cave. Not amused.)

It was mainly a joke, what I wrote, but a mere two months on, we’re alarmingly close. Indeed all manner of AI has been leaping into the news, especially the text generation of ChatGPT and its host of rivals, able to spool out endless articles, scripts, automated search responses and more, all on demand, and clean enough for some websites to have tried flooding the web with AI-generated content, in order to pull traffic and ads and money, while potentially saving on their staff.

(Not us at whathifi.com, I should say, or at least, not that I know of. Of course if I were to be ousted by a bot, presumably the first I’d know is when my connection is suddenly c… )

This feature originally appeared in Sound+Image magazine, Australian sister publication to What Hi-Fi?. Click here for more information on Sound+Image, including digital editions and details on how you can subscribe.

Only kidding; still here. I remain elbows deep in AI art; I love it. and I'm actively using it in Sound+Image magazine. Only a year or so ago, public versions of AI art were interesting but pretty crude. By the end of 2022, the images became brilliant, and startling.

You can lengthen prompts to include details, art styles, materials, lens types. You can use your own picture as a reference, then use a prompt to turn it into something else. Example: the images above each started as a pic I took of the Audio-Technica Sound Burger in for review, varied with various prompts.

The latest hi-fi, home cinema and tech news, reviews, buying advice and deals, direct to your inbox.

My prompt for the one in the middle of the second column, for example (click top right of the image to make it bigger), was fairly abstract: “Just an illusion. Super detailed masterpiece artwork on show in a circus.”

These were created using the Stable Diffusion AI art engine via playgroundai.com. It’s free, for now.

The whole idea of AI-generated art is, of course, diametric. Artists and graphic folk tend to seethe or rage, entirely understandably. And this isn't helped when people sneak AI images into photography competitions and then win – as happened in Australia recently. The image was entered by an AI company, Absolutely AI, as a promotional stunt, to show the quality of its images, and they returned the prize money. A fist-pump for AI art fans; abject horror for photographers.

I'm with the AI art fans. I’ve never been able to draw, so for me it’s like I’ve been upgraded overnight. Others just can’t see the point of it: the missus, for one. She fears I’m addicted to creating stupid images, and engages with me like a five-year-old – “So what have you made? ‘Kermit leads the Muppets into Mordor’? Yes, it’s very nice, dear.”

Sadly I can’t show you ‘Kermit leads the Muppets into Mordor’ because clearly that crosses some line in copyright or trademarks or something. (But I can tell you the picture is awesome.)

And this is a shadow (copyright and trademarks, not Mordor) which hangs over all of AI art. These AI programs have been trained on any number of freely-available tagged images; the program breaks down their essences, and recombines them to deliver its response to a prompt.

AI art enthusiasts point out that this is exactly the process of a real artist, absorbing influences and ideas over the years, and then drawing something new. Whereas artists say that if any of their own particular essences show up in your art, they’ll sue your arse.

So who is now the artist: the prompter, the AI, or the AI’s sources? The AI art engines say you have (shared) copyright. The US Copyright Office recently made a ruling indicating it thinks there may be no copyright possible at all, because – as with that famous monkey selfie – works created by non-humans can't be copyrighted.

But soon they'll realise that such a ruling might make it impossible to copyright, say, all the computer graphics ever generated, and that machines don't create on their own. AI art is governed by the quality of the text prompt. One thing I love about AI art is that the better your language skills, the better you can make the art; the prompts are thoroughly human and entirely creative. But for sure this debate will run until some court makes a call on it.

Flat chat

As for AI chatbots, you don't need me to tell you how ChatGPT et al is already changing the world. But I’m moderately confident I won’t (yet) be pasting any bot text into Sound+Image magazine. I keep trying text engines and chatbots to see how they’re going, and basically they tend toward the wildly bland and mildly inaccurate.

And that’s exactly as one might expect from a process which is effectively averaging the internet, boiling it all down, so that it’s likely to generate the text equivalent of the grey mush into which all matter will eventually decay once the nanobots get out of control. (Don’t worry, it could be years away.)

The ‘mildly inaccurate’ bit has thankfully been making headlines – not only in the rarefied segments of Media Watch, but at the grand launch of Google’s ChatGPT rival 'Bard', where part of the demo response up on the big screen was clearly inaccurate. This apparently surprised a lot of people, which would suggest those people haven’t been using much AI. AI is very often surprising, and very often inaccurate. All this offers great hope to the humble journalist.

So yes, I hesitate to say ‘watch and see’, because next thing you know you’re thrown to the side of the road as the Next Big Thing barrels up the highway, or you wake up with only an arm left in a sea of grey goo. So I’m keeping my eye in.

And my ear too, more recently, because while my AI-making time is still largely expended on the pictures, I’m actively playing with… drum roll... AI sound generation.

AI sound

The AI art programmers have already introduced video generators – primitive, but it’s early days. (Although if you're reading this in six months, they're probably all over the web by now.)

And yes, AI sound. It has taken significant strides in the last couple of months, with new engines appearing, and existing ones suddenly boosting their quality, databases and user numbers.

One area recently getting publicity is text-to-audio; this has been around a long time, with avatar-type voices. This is now accelerating rapidly with AI models, though it’s hard to get invites to some of the trials. And as with all AI, it’s getting much harder to do more than a little of it for free.

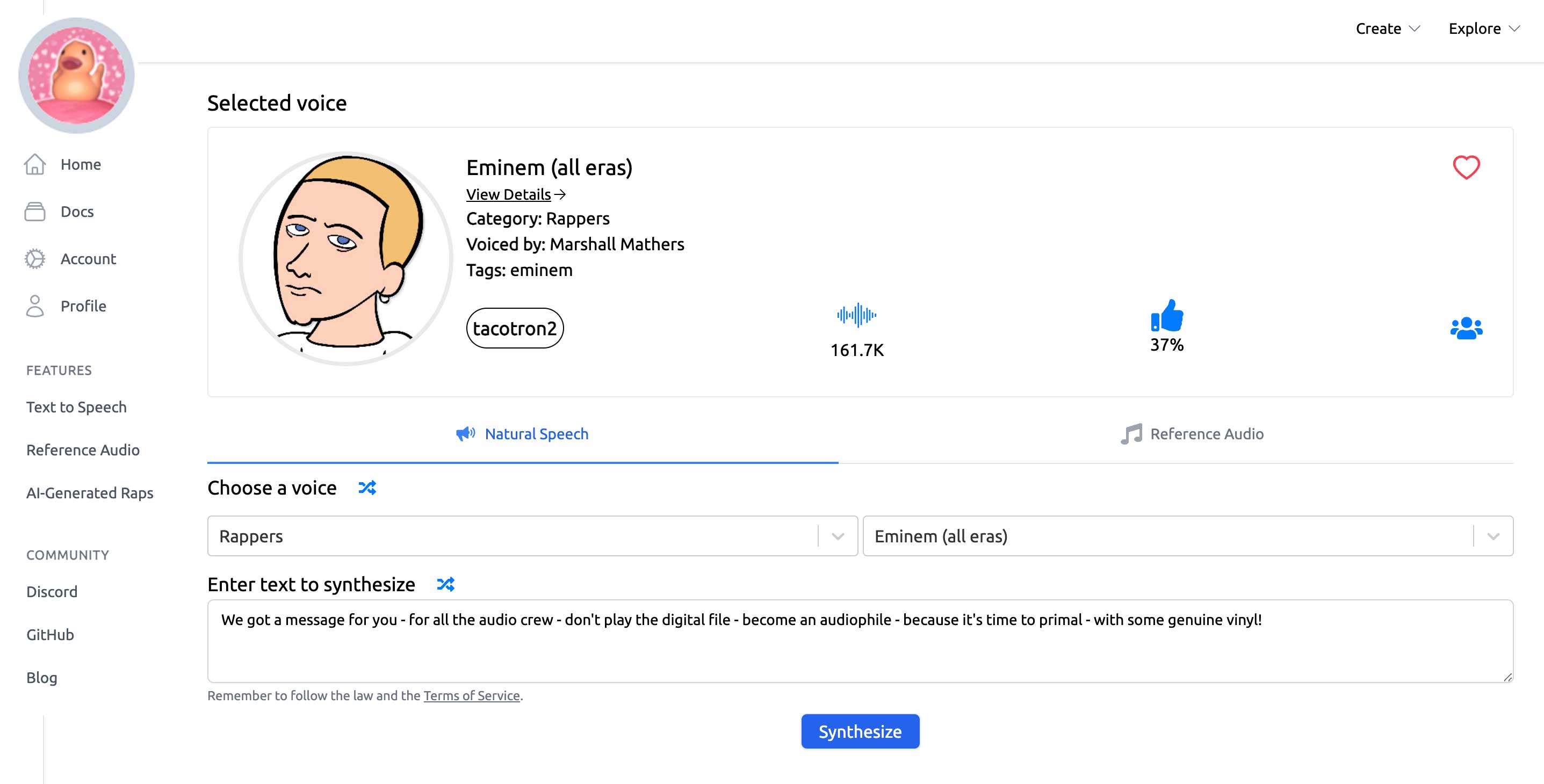

So Uberduck (above) has been around since 2020; it's got traction on TikTok, and it's getting better all the time. It can do Eminem raps and a host of other voices – 2000+ on the free plan – so many, indeed, that there's a voting system allowing the crowd to separate the appallingly bad from those that are getting there.

None of them is perfect, or at least, none that I tried. Of the five current Eminem variations I'd recommend 'Eminem (all eras)', but if you were being clever you'd download results from each of them and cut together the best bits. Stephen Fry and Shrek are pretty good. The paid plans presumably access the best selections.

But I'm more interested in sites that create audio and music. And remember this is not a case of messing with existing music or sound effects; it's generating audio from diffusion models which remove everything and then rebuild it until it matches the prompt to the satisfaction of the engine. It's entirely artificial, or at least, it claims to be; who knows what creators will claim to have had their essences misappropriated in this regard.

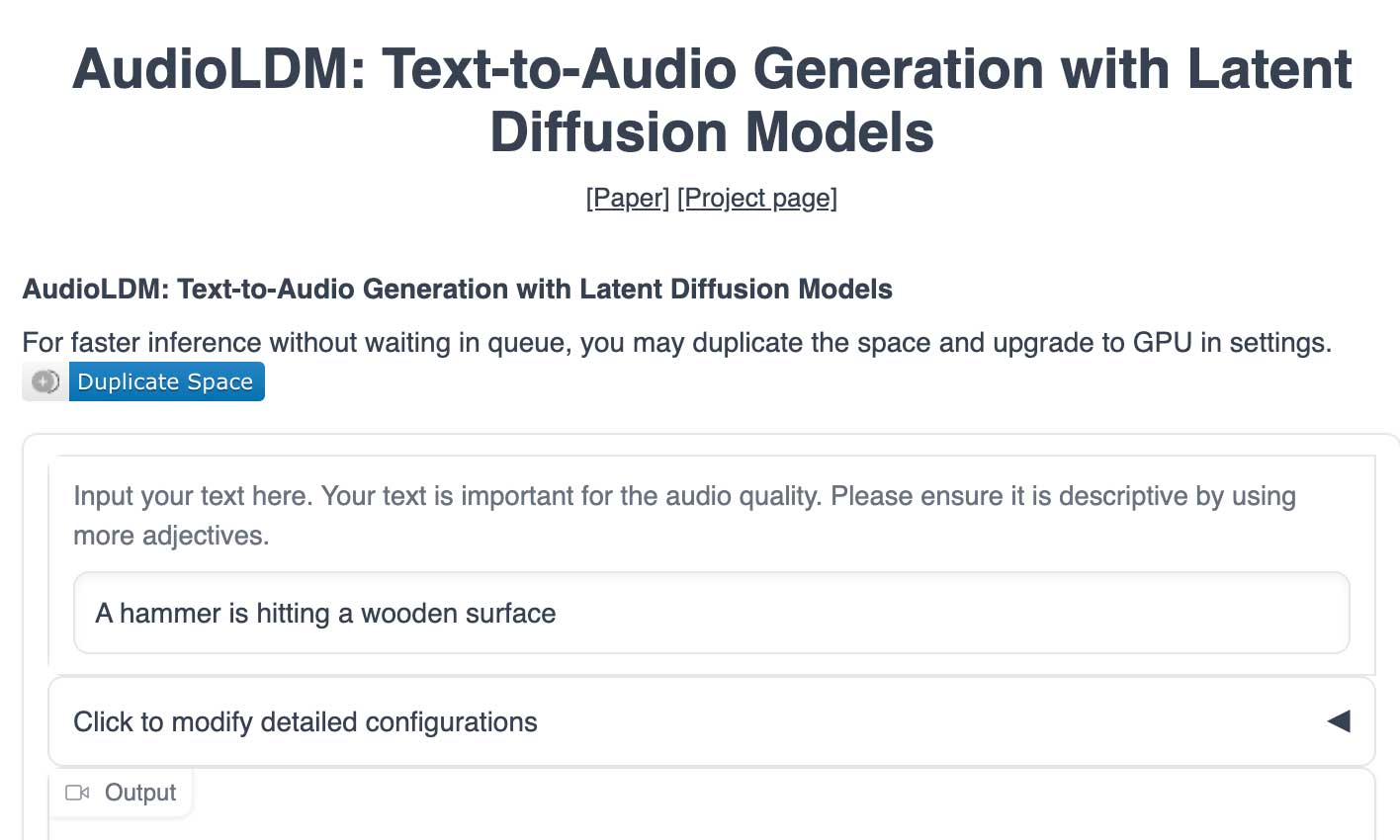

AudioLDM is interesting – a simple text-to-sound engine, which is up on Hugging Face's AI community platform (image above).

Its built-in suggestion reads, “A hammer is hitting a wooden surface”, but we went a bit more abstract and requested “a woodland glade full of fairies”. It returned a 30-second clip of mono low-bit Brian Eno with birdsong over the top — not at all unpleasant, though perhaps you wouldn’t want a whole evening of it.

Harmonai looks promising, but goes to the coding level, too hard for me.

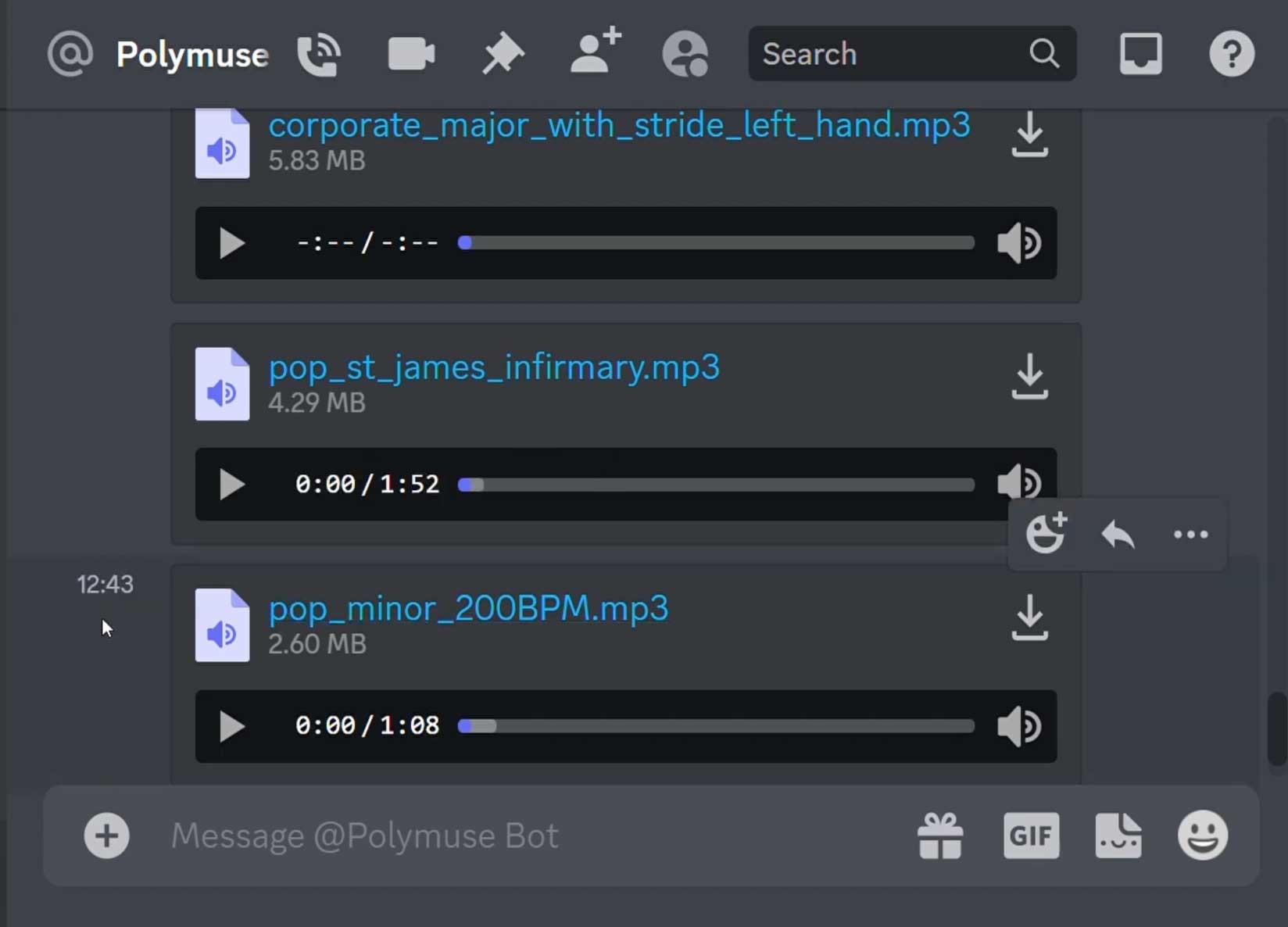

I did score a Discord invite to Oranion’s Polymuse, which is far more musically-minded. There are no fluffy descriptions allowed here, but rather the ability to combine styles from an expanding list, then define key and chord progressions, BPM and more.

The results (judging from his own samples, as I somehow blew my invite) are musical, diverse, and controllable in interesting ways. It's currently a closed beta, but Delphos has posted some Polymuse creations on Soundcloud here.

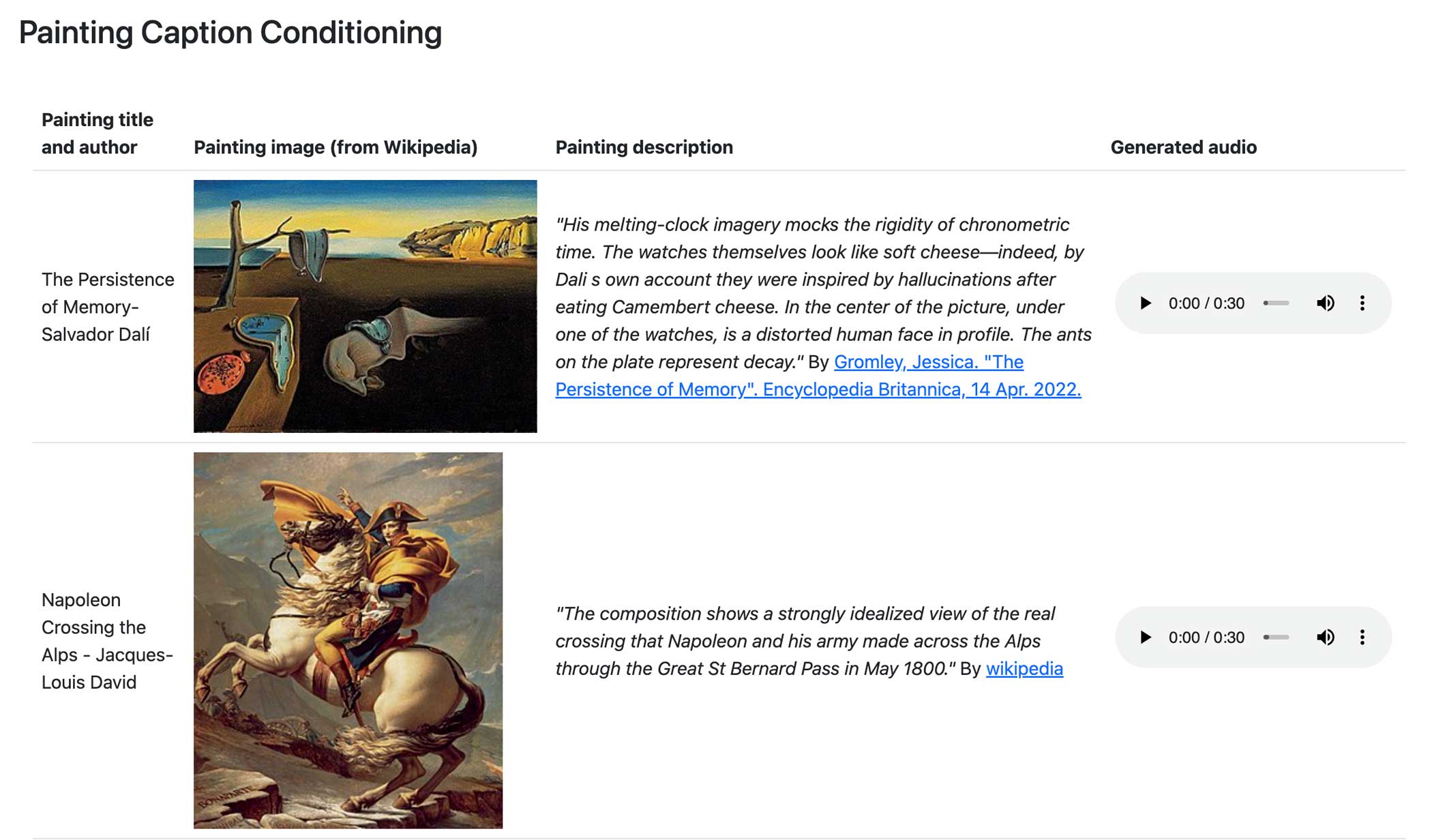

The designers of all such systems must have been a bit gutted by the arrival of Google Research’s MusicLM, which popped up at the end of January, although it has clearly evolved from the earlier AudioLM experiment.

It is wildly more sophisticated than the others and, judging again from samples on its webpage, perfectly happy with abstract instructions – there are examples where descriptions of paintings have been fed into the generator.

And MusicLM's music? Well, it’s low-bit for now, but really interesting, and complex; the engine must be very well-trained. MusicLM’s vocals are all wordless tunes, endless Elizabeth Fraserisms, so that’s an obvious oddity, though some are finding them strangely beautiful.

The potential applications seem endless, especially anywhere that requires non-copyright background music. Need a film soundtrack? Paste in your scene description and get four options back in a minute. Let’s try that filter that makes it sound like Nick Cave & Warren Ellis. (Sorry, Nick.)

Currently MusicLM is able to “generate music at 24kHz that remains consistent over several minutes”. Its vocals are hilarious – all wordless tunes, as if Elizabeth Fraser has taken over the world.

Again, of course, it’s not hard to see a downside: for musicians, stock music companies, everyone in lifts and supermarkets. You’d expect the whole idea to be bought up and shut down by Muzak, or Neil Young, but hey, this is Google, nobody is shutting down Google (except possibly ChatGPT).

But Google may itself be thinking hard about the consequences, because as yet they’re not letting MusicLM loose; it’s just demonstration only. But really, have a look and a listen to AI music demos here.

It’s certainly the AI engine I’d most like to be prompting right now.

Next month? Who the freak knows. But I'm ready for it!

MORE:

It's official, the first "high-resolution" wireless headphones are coming

Sony announces 2023 TV range, including '200% brighter' A95L QD-OLED

Tickets on sale now: Join us at the Australian Hi-Fi Show 2023 in Sydney!

Jez is the Editor of Sound+Image magazine, having inhabited that role since 2006, more or less a lustrum after departing his UK homeland to adopt an additional nationality under the more favourable climes and skies of Australia. Prior to his desertion he was Editor of the UK's Stuff magazine, and before that Editor of What Hi-Fi? magazine, and before that of the erstwhile Audiophile magazine and of Electronics Today International. He makes music as well as enjoying it, is alarmingly wedded to the notion that Led Zeppelin remains the highest point of rock'n'roll yet attained, though remains willing to assess modern pretenders. He lives in a modest shack on Sydney's Northern Beaches with his Canadian wife Deanna, a rescue greyhound called Jewels, and an assortment of changing wildlife under care. If you're seeking his articles by clicking this profile, you'll see far more of them by switching to the Australian version of WHF.