Don't believe the hype: Bluetooth LE and the LC3 codec won't improve audio quality

Announcements regarding Bluetooth LE and the new LC3 audio codec need to be treated with caution

The latest hi-fi, home cinema and tech news, reviews, buying advice and deals, direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Only last issue in the print magazine of Sound+Image, I was having a whinge about companies and organisations that claim there is such a thing as Hi-Res Audio Wireless. There just isn’t – at least not via Bluetooth, and not losslessly, which is what high-res audio is all about.

The Bluetooth codecs which claim high-res performance, like Qualcomm’s aptX HD and Sony’s LDAC, are all lossy, throwing away data they think they don’t need or that they think we can’t hear. That allows them to get a signal to emerge at the other end in what may be 24-bit/48kHz or 24/96, but with data thrown away. And for me, that’s not high-res audio, which is all about keeping the entire thing intact and unsqueezed. One of my fellow EISA editors, John Darko, has joined me in efforts to make this clear. (He gave me a shout-out in a recent piece, so here's one back.)

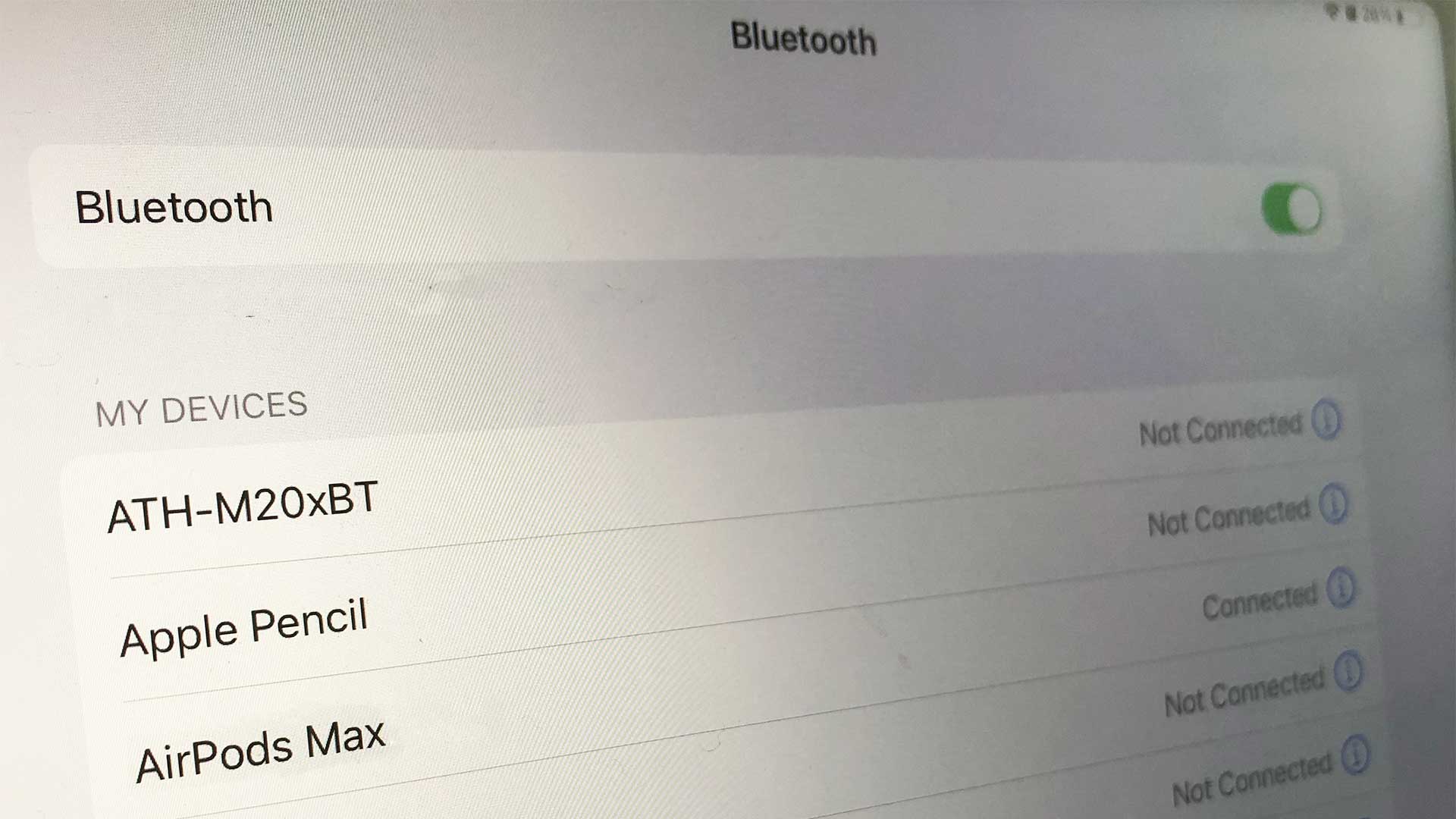

There is now aptX Lossless, which allows lossless CD quality via Bluetooth transmission, but not high-res audio. This is just beginning to turn up in Android phones (more next year, we gather), and it is on a promise to appear in the new (and pleasingly Australian) nura NuraTrue Pro earbuds, and a couple of others.

Given you need both your phone and your headphones to support aptX Lossless for the codec to work, for now you’ll be doing some very specific gear shopping just to activate this codec, and Apple users can go whistle.

But it’s certainly good that third parties have pushed things as far as this lossless CD quality via Bluetooth. But not lossless high-res.

Bluetooth LE Audio and the LC3 codec

Now then, you may have seen exciting news about the new wave of Bluetooth on the horizon, with the Bluetooth Special Interest Group (SIG) announcing a full set of specifications, including a whole new standard audio codec.

This new audio codec is called LC3, and when we look at the size of the Bluetooth SIG today, we should congratulate it on having achieved anything at all. This group has grown from its founding five companies in 1988, then led by Ericsson, to now some, er, 30,000 member companies. It must take weeks even to count their votes.

The latest hi-fi, home cinema and tech news, reviews, buying advice and deals, direct to your inbox.

Anyway, audio geek that I am, a new Bluetooth codec is exciting stuff to me, and I grabbed the new LE and LC3 spec with enthusiasm.

I was disappointed. Perhaps I should have known better, because ever since I attended an early launch of consumer Bluetooth back in the late 1990s, I have waited through the umpteen updates since then for the Bluetooth SIG to allocate more bandwidth for audio. More bandwidth, a higher bit-rate, is the only way you can get better audio quality through Bluetooth, or at least, the only way to achieve it without throwing away some of the music.

But every time a new version of Bluetooth has been announced in the two decades since then, the advances have always been all about reducing energy use, or increasing range, so that Bluetooth devices can be smaller and further away or use less power. Not once did the Bluetooth SIG vote to increase available bit-rates for audio. The Enhanced Data Rate of Bluetooth 2.0 and 2.1 in 2005-7 did increase data overall but not for audio specifically. So third-party codecs like LDAC and aptX which have pushed beyond the standard SBC or AAC have done so by hijacking other non-audio bits of Bluetooth and using them for extra data. Though never enough to achieve lossless high-res audio.

Even though Bluetooth can theoretically pass up to 3Mbps, which is more than enough for, say, 24-bit 44.1kHz, in practice the combination of real-world conditions and all the bits given up during the packeting process of A2DP means that you’ll be lucky to get 1Mbps of useful data actually passing through, which is why LDAC and aptX’s top codecs all work around those rates. Even then they need to include ‘adaptive’ quality reduction for when things get messy in a busy RF area.

All these codecs necessarily use what is known as Bluetooth Classic mode; the full-fat version of Bluetooth.

But there has also been Bluetooth LE (Low Energy) alongside, which is sometimes used as a secondary Bluetooth connection made by headphones or audio gear for either control or for low-bit-rate voice transmission. Just occasionally we’ve had headphones that have accidentally jumped to LE for their audio transmission, which is easy to spot, because it sounds like shit.

So, now, the new development – an improved version of Bluetooth LE, and it includes Bluetooth Low Energy Audio, which “makes lower battery consumption possible and creates a standardised way of transmitting audio over BT LE”.

Now this has definite advantages — Bluetooth LE Audio will allow your device to send multiple Bluetooth streams simultaneously, so several people can listen to one phone (wait for the copyright issues to surface on that one), or venues can broadcast Bluetooth audio to multiple users at once, which might be for a silent dance party, or using a QR code to let TVs in public places interrupt your listening with adverts. (This will be known as AuraCast.)

Sounds good? Not really, because to achieve this, they’re actually reducing the bit-rate for audio. It may be higher than LE could manage before, but it’s far lower than Classic Bluetooth can manage. A demonstration available on www.bluetooth.com maxes out with LC3 encoding to 248kbps. If I’m reading the spec right, its compatibility tops out with input files at 44.1 or 48kHz, so there’s no high-res in frequency terms, though it can take 32-bit data, so it can be high-res in terms of sample accuracy. But it’ll have to throw a lot of that away to hit 248kbps.

So why are various websites (including ours, here) saying this will improve the sound?

This assertion is based on the new LC3 codec being better than SBC. The Bluetooth.com site shows the results of listening tests in which they’ve proved this. But I'm old enough to remember back to when Fraunhofer, the inventors of MP3, said very similar things about the listening tests they did with MP3s, and look where that ended up – with decades of low-res audio.

So who is behind the new LC3 codec? Oh, it’s Fraunhofer again. How reassuring.

We should also note that Fraunhofer has an 'LC3plus' or 'LC3plus HD' codec, which does go up to 24-bit/192kHz transmission; the company sees it for use in DECT wireless comms as well as potentially for high-res audio streaming, noting it will be "the only open-standard audio codec for high-resolution wireless headsets and high-quality gaming headsets". Yet its spec sheet (a dazzling 163 pages) seems to indicate that 24/96 signals would not fit within the practical 1Mbps available even to Bluetooth Classic. So LC3plus seems more for streaming high-res music from the web to your device, rather than from your device to your headphones.

As for the Bluetooth LE implementation, maybe LC3 does succeed in sounding way better than SBC; we will find out when we start getting devices and headphones able to support it over the next few years.

But this development does not advance the bit-rate available for audio overall. Indeed the problem on the horizon may be that headphones supporting LE audio will actually start to ditch the higher quality Bluetooth Classic codecs, as the brands will be shouting about the fab ability of the new chip-sets to connect with multiple headphones, with longer ranges and better battery life.

In other words, unfortunately it seems to be business as usual. The new Bluetooth is a step backwards for absolute audio quality, in order (yet again) to improve battery life and do clever other things while squeezing the audio bit-rate and still trying to persuade people it’s going to sound better.

But by “better”, they mean only “better than shit-house SBC”. Well we’d blooming hope so! Does it sound better than AAC, aptX or LDAC over Bluetooth Classic? Almost certainly not. Better than a cable to your headphones, the only way to play genuine high-res audio? Not a hope.

My advice? Don’t believe the hype. Use your ears.

Jez is the Editor of Sound+Image magazine, having inhabited that role since 2006, more or less a lustrum after departing his UK homeland to adopt an additional nationality under the more favourable climes and skies of Australia. Prior to his desertion he was Editor of the UK's Stuff magazine, and before that Editor of What Hi-Fi? magazine, and before that of the erstwhile Audiophile magazine and of Electronics Today International. He makes music as well as enjoying it, is alarmingly wedded to the notion that Led Zeppelin remains the highest point of rock'n'roll yet attained, though remains willing to assess modern pretenders. He lives in a modest shack on Sydney's Northern Beaches with his Canadian wife Deanna, a rescue greyhound called Jewels, and an assortment of changing wildlife under care. If you're seeking his articles by clicking this profile, you'll see far more of them by switching to the Australian version of WHF.