What Hi-Fi? Verdict

While the M3x Vinyl from Musical Fidelity only sets out to achieve one thing – accomodate a single phono cartridge – it achieves this with stellar results. While it can handle both MM (moving magnet) and MC (moving coil) cartridges, it can only support one at a time due its singular unbalanced input.

Pros

- +

Glorious sound

- +

Useful loading

- +

IEC-RIAA Equalisation

Cons

- -

Single input

- -

Single output

- -

Unbalanced only

Why you can trust What Hi-Fi?

This review and test originally appeared in Australian Hi-Fi magazine, one of What Hi-Fi?’s sister titles from Down Under. Click here for more information about Australian Hi-Fi, including links to buy individual digital editions and details on how to subscribe.

The Musical Fidelity M3x Vinyl MM/MC phono stage is a first for Musical Fidelity in more than one way. First, it’s the first phono stage in the company’s M3 Series, which Musical Fidelity promotes using the catch-phrase “Great-looking, superb-sounding hi-fi doesn’t have to cost a fortune. Our M3 range offers an elegance of design, quality of build and standard of finish you’d associate with products costing twice as much.”

The M3x Vinyl is also the first Musical Fidelity component to be built entirely in countries in the European Union. This is a significant switch that requires some explanation.

When he started the company back in 1982, Anthony Michaelson built Musical Fidelity products exclusively in the United Kingdom. He later switched production of most of his products to Taiwan. However, in 2018 Michaelson sold Musical Fidelity to his good friend Heinz Lichtenegger, the owner of Pro-Ject, who with his wife Jozefína (who owns European Audio Team, also known as E.A.T.), have between them multiple high-tech manufacturing facilities in the EU. The M3x Vinyl is the first Musical Fidelity product to be built in one of these facilities.

It remains to be seen whether Lichtenegger will start manufacturing other Musical Fidelity components in the EU.

The M3x Vinyl is also almost the first phono stage Musical Fidelity has manufactured that does not use op-amps (operational amplifiers), instead using discrete components (separate resistors, capacitors, transistors and so on in the place of op-amps. This is rather the opposite of what’s happening in other hi-fi components, so we asked Musical Fidelity the reason for it.

The answer, according to the company? “Countless hours of listening tests have shown us that even the very best op-amps do not tend to be so neutral, natural, dynamic or vivid – all of which are characteristics of the Musical Fidelity sound. For that reason, we’re rediscovering our passion for traditional, discrete designs.”

Musical Fidelity is not the first company to eliminate op-amps from its circuits. Marantz famously uses op-amp replacements it calls HDAMs and here in Australia, local high-end manufacturer Burson Audio builds what it calls ‘Supreme Sound’ op-amp replacements that it sells to other manufacturers as well as to DIY upgraders.

The latest hi-fi, home cinema and tech news, reviews, buying advice and deals, direct to your inbox.

Burson Audio’s Supreme Sound ‘op-amps’ are comprised entirely of discrete devices. Each one is about 40 times the size of its IC equivalent and comprises 24 matched FETS (Field Effect Transistors), 16 metal film 0.5% tolerance resistors, a pair of silver mica capacitors and a pair of variable resistors. This means that a manufacturer that replaces a single dual op-amp with discrete components will have to solder in (and make room for on the circuit board) 44 components. This means you’d need almost 900 discrete components to replace just 20 dual op-amps.

But the M3x Vinyl wasn’t the first Musical Fidelity product to eliminate op-amps. It was the second.

The first was the M6xVinyl phono pre-amplifier, a component that in many ways is very similar to the M3x, which we’ll discuss later on in this review. However Musical Fidelity hasn’t only removed op-amps from the M6x Vinyl, it has also removed all the active circuitry that’s usually used to provide RIAA equalisation and instead provides the all-essential RIAA equalisation using a completely passive circuit.

What’s more, it’s divided this passive circuit into two different circuits. Musical Fidelity says its split passive EQ circuitry: “is more costly to design and implement but ensures the most accurate representation of the ideal EQ curve. Split passive equalisation allows for better impedance matching and less deviation from the ideal RIAA curve.”

In order to understand what this all means, and why it’s so important, we need to delve a little more deeply into RIAA equalisation and the whys and wherefores of how it can be implemented – active or passively.

Passive vs. active RIAA EQ

The purpose of a phono stage – its raison d’etre, if you like – is to ‘correct’ the frequency response of the signal the diamond tip of your phono cartridge’s stylus is extracting from the LP’s groove. This comes about because in order to ‘store’ music on an LP the cutting engineer has to pre-attenuate the levels of the low frequencies and pre-boost the levels of the high frequencies. At the midway point (1kHz) there is no boost or cut. This is the 0dB point.

As the music being recorded on the LP gets progressively lower in frequency, its level is progressively reduced until at 20Hz it is 19.3dB lower than the 0dB reference at 1kHz.

The opposite happens with frequencies above 1kHz. The higher the frequency of the music being recorded, the more the audio signal is boosted until, at 20kHz, it’s boosted to +19.6dB.

Because the levels of boost and cut applied are different for every different frequency, the overall effect is described as an ‘equalisation curve’, the most common of which is the RIAA curve, so-called because it was developed by the Record Industry Association of America.

So in order to ensure the correct response is sent to your main amplifier and then to your speakers, a phono stage must provide an ‘inverse’ RIAA curve that restores all the frequencies to their correct levels, for example boosting the bass at 20Hz by 19.3dB and cutting the treble at 20kHz by 19.6dB.

But what happens below 20Hz? If the RIAA equalisation boosts frequencies below 20Hz, this means that unwanted low-frequency sounds from your turntable (drive motors, bearing noise and so on) as well as from your LPs (record warp and sounds actually inadvertently recorded at the original recording session) would be made more audible. It is for this reason that in1976, Europe’s International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC), decided to authorise the RIAA replay curve to be modified in such a way as to reduce (attenuate) frequencies below 20Hz.

It wasn’t an entirely popular solution to the problem of low-frequency noise, because the circuitry required introduced amplitude and phase errors into the frequency response above 20Hz, and the circuit’s action was so mild below 20Hz that it really didn’t do a lot to remove rumble, particularly if that rumble occurred between 10 and 20Hz.

Most manufacturers decided a better option was to use a standard RIAA replay curve but provide a dedicated ‘rumble filter’ that provided far more attenuation at low frequencies than the IEC RIAA variant.

As for the means of providing RIAA equalisation, the circuitry required to do this can be implemented in two different ways – actively or passively. Active RIAA equalisation involves using voltage gain and feedback loops that adjust the frequency response depending on the amounts of feedback returned to the input. One advantage of active equalisation is that exact component values in the circuit are not crucial and that left- and right-channel matching is largely unnecessary. One disadvantage is that, because it is active, the circuit is prone to input overloads.

There’s also the problem that an active circuit must have a very high voltage gain in order to deliver the level of compensation required to boost low frequencies by 19.3dB as well as providing the additional gain necessary to bring the circuit’s output up to the necessary one or two volts required to feed the line input of a hi-fi amplifier (or pre-amp).

The problem with gain is that the more of it you use, the more unstable a circuit becomes and the more phase shift you introduce. A solution circuit designers often use to get around these problems is to split the equalisation process into two, and use one active circuit to manage frequencies below 1kHz and another to manage the frequencies above.

The alternative to active equalisation is passive equalisation, so-named because only ‘passive’, non-powered, components – resistors and capacitors – are used to create the RIAA equalisation required.

The advantages of passive equalisation include that the input can’t be overloaded and because there is no feedback, the circuit is completely stable.

However the disadvantage is that because the circuit is passive, no ‘gain’ is possible (this has to be done by a separate circuit) and the performance of a passive circuit will be affected by the phono cartridge’s own resistance and capacitance, as these effectively become part of the circuit itself.

To get around most of these problems, designers of passive RIAA equalisation circuits usually take a leaf from the circuit’s active counterpart, and use two passive networks, one for frequencies below 1kHz and the other for frequencies above.

Features and facilities

The front panel of the M3x Vinyl phono stage pretty much gives away exactly what features it has inside it because they’re all printed right there on the panel itself.

You can see that the unit will accommodate both moving-magnet (MM) and moving-coil (MC) cartridges but despite the provision of two push-buttons to select between them, there’s only a single phono input on the rear, so you can connect either the one or the other, but not both simultaneously.

If you are using a moving-magnet cartridge, the six push-buttons just to the right of the two MM/MC selector buttons allow you to choose what load capacitance will be presented to your cartridge: 50pF, 100pF, 200pF, 300pF 350pF or 400pF. Whichever of these load capacitance values you select, the value of the load impedance will remain fixed at 47kΩ. The gain of the MM section is fixed at 40dB.

If you are using a moving-coil cartridge, the six push-buttons at the far right of the front panel allow you to choose the load impedance that will be presented to your cartridge: 25Ω, 80Ω, 100Ω, 400Ω 800Ω or 1.2kΩ. The gain of the MC section is fixed at 60dB.

Between the MM and MC load-setting buttons are two buttons, the left-most of which is labelled ‘IEC’ and the rightmost ‘+6dB’. What the IEC button does is switch the M3x Vinyl’s equalisation curve from being a standard RIAA curve to an IEC-RIAA curve.

As for that ‘+6dB’ switch, it activates an additional amplifier stage that adds an extra 6dB of gain to increase the voltage at the M3xVinyl’s output terminals (which, by the way, are standard unbalanced types, using RCA connectors). So activating this circuit will mean that moving-coil cartridge output voltages will be boosted by a total of 46dB (40dB + 6dB) and moving-coil cartridges by 66dB (60dB + 6dB).

What the previous paragraph means in real life is that without the additional gain stage if your moving-magnet cartridge was delivering 5mV to the M3x Vinyl’s input terminals, you’d have 500mV at the output terminals. For a moving-coil cartridge delivering 0.5mV, you’d have 500mV at the M3xVinyl’s output terminals.

If you press the +6dB button in, those output voltages would double, to 1000mV, or one volt (1V) for the same inputs noted previously.

As explained earlier in this review, the more gain stages you introduce during the equalisation process, the more you increase the possibility of errors being introduced, so if you can achieve adequate volume levels from your loudspeakers without using the additional 6dB of gain on offer, my advice would be to leave it switched off.

If you try to compare the ‘sound’ of the two gain settings by alternately pressing the button on and off, you should be warned in advance that this is a waste of your time, because the sound will always seem to improve when you switch to the +6dB setting. This is a trick your brain is playing on you, because given two otherwise identical sounds, the human ear will always prefer the louder one over the softer one. Why do you think rock bands sound so good at live concerts?

As for the final button on the front panel, the ‘Power’ button, I’ve left that to last because it’s rather curious. It’s not an On/Off switch. It instead switches the M3x Vinyl between ‘On’ and ‘Standby’. The reason I say the switch is ‘rather curious’ is because Musical Fidelity’s promotional literature claims the M3x Vinyl is fitted with – and I quote verbatim – “a new proprietary power supply solution that has zero standby power consumption. Absolutely zero! It is a super green product and we are sure, there isn’t any other product in existence with an ecological standby function like this.”

This statement is, of course impossible and, therefore, not true.

The Musical Fidelity M3x Vinyl does draw power in its standby mode, but it draws it not from the mains power, but from a 3V CR2030 battery inside it. This battery ensures that whatever cartridge type, load and gain settings you were using when you switched the M3x Vinyl off will be restored when you next switch it on.

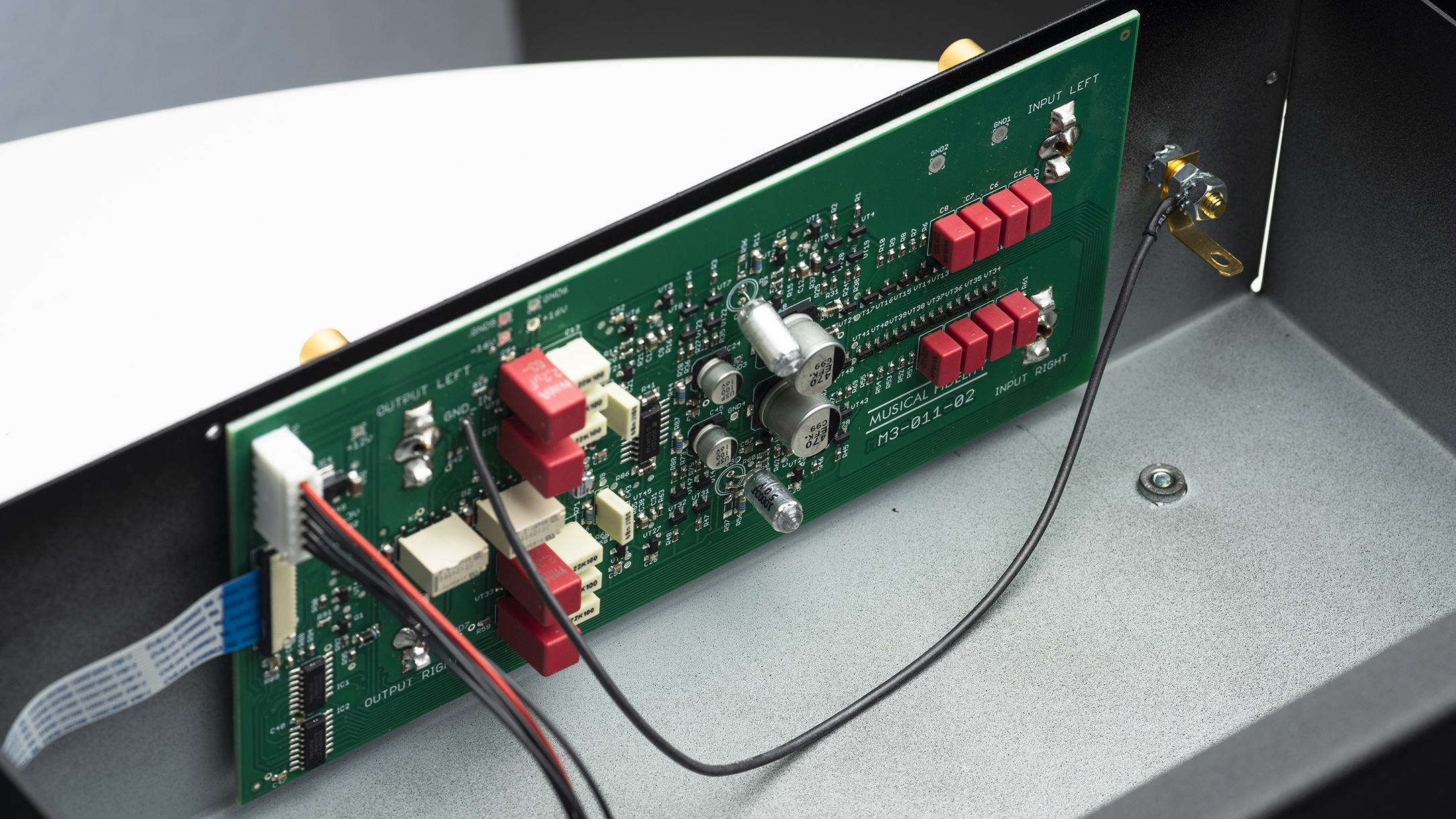

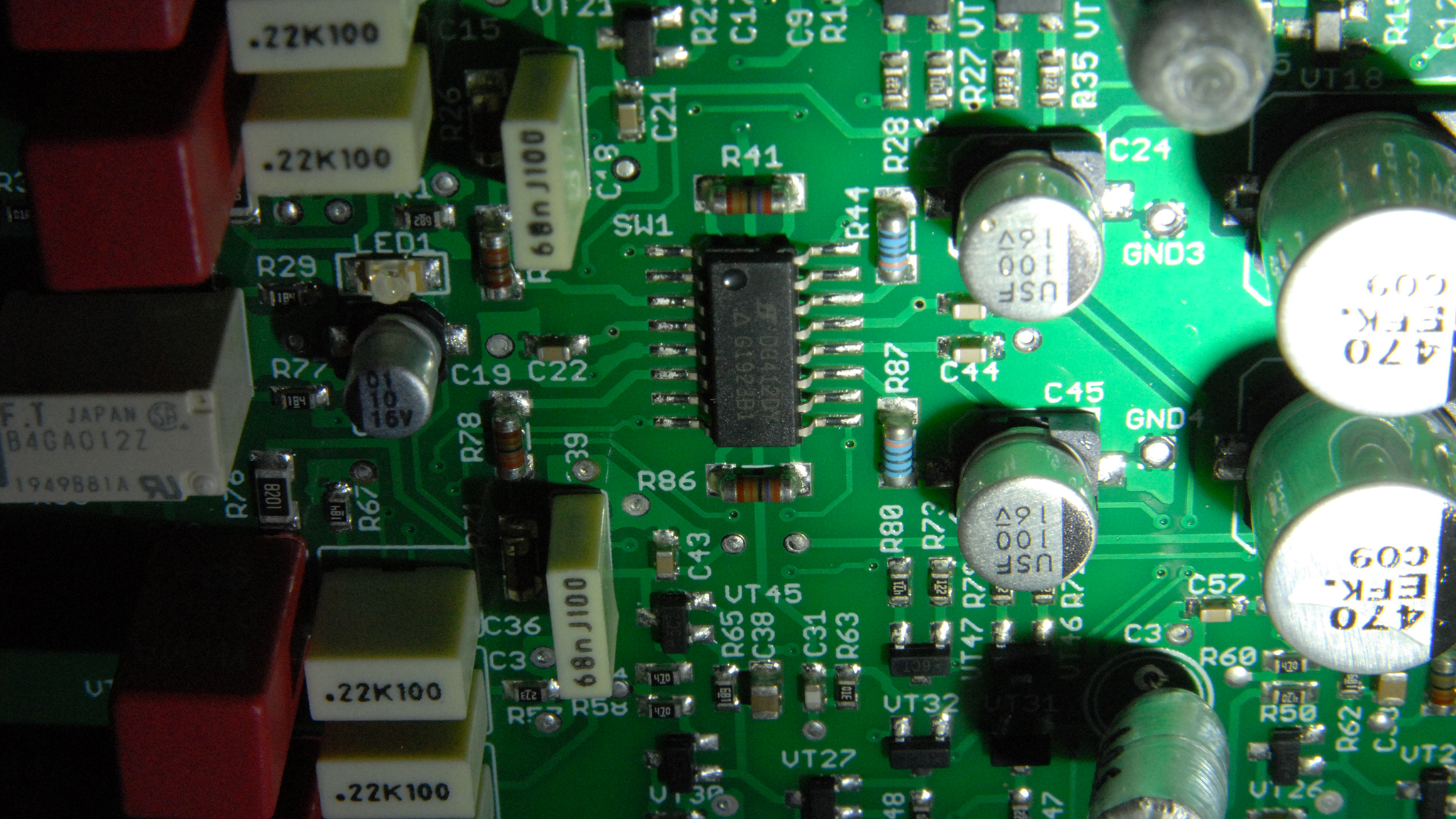

Take a look inside the M3x Vinyl and you’ll not only see the battery, but also that the PCBs inside it take up so little space that Musical Fidelity could, theoretically, have made the chassis a good deal smaller than it is, but one reason for its physical size is that it enables the designers to position all the unit’s power supply components on a separate printed circuit board (PCB) and mount it as far away from the primary circuitry as possible.

They’ve also used a totally shielded low-core saturation toroidal transformer to step down the 240V mains voltage to the amplifier’s rail voltage. Look inside very carefully and you’ll see that while Musical Fidelity hasn’t used any op-amps in the circuitry of the M3x Vinyl, the circuitry is not, as the company claims, “entirely discrete” because the PCBs do contain integrated circuits, including an STM32F030F4P6TR 32-bit 16kB 48MHz ARM micro-controller.

Worthy of special mention is the all-essential turntable ground post fitted to the rear panel of the M3x Vinyl. It’s simply the best such terminal I have ever seen on any phono stage, or pre-amp or integrated amplifier. It’s a full-on brass screw fitting not unlike a speaker terminal. So much better than the horrible plastic/arrow prong terminals that are usually provided.

Listening

If you use a high-quality phono cartridge, it is essential to also use a high-quality external phono stage if you’re to extract the best performance from it. The phono stages built into even the best high-end pre-amplifiers and integrated amplifiers simply won’t do it justice, most particularly if you’re using a moving-coil cartridge.

I first listened to a brand-new LP I’ve just purchased, but one with which I was intimately familiar, having listened to earlier versions of it for more than two decades. That LP was the 45rpm version of ‘L. A. Woman’, by The Doors, pressed by Analogue Productions.

It’s a part of a six-disc set which makes up The Doors’ six studio LP titles (the others being ‘The Doors’, ‘Strange Days’, ‘Waiting For The Sun’, ‘Soft Parade’, and ‘Morrison Hotel’). All were cut by the legendary Doug Sax using the original analog masters. According to Doors producer/engineer Bruce Botnick, in order to play the original tapes they had to be baked in an oven to make sure the layers didn’t stick before they could be replayed!

Of course L.A. Woman has Love Her Madly on it which was a No 1 here in Australia, a No 3 in Canada and reached No 11 on Billboard’s Hot 100 chart when it was released as a single. But look past Love Her Madly and you have such unbelievably good tracks as Riders on the Storm, L’America, Been Down So Long, The Changeling and, of course, the title track. Game-changers of songs all.

For my money, the outstanding musician on Love Her Madly is bass player Jerry Scheff, who once played bass for Elvis Presley. Listening via the Musical Fidelity M3x Vinyl I was able to appreciate even more how he manages to be totally inventive, with unusual bass lines that drive the song and create an underlying pulse, while all the time containing the song’s break-neck tempo (one of Scheff’s jobs was to make sure keys man Ray Manzarek didn’t play too fast!).

The M3x Vinyl revealed the tone of his bass better than I’ve ever heard, and also delivered the best stereo image I’ve heard from this track, given that it was recorded wide, with instruments played mostly left and right, rather than spread across the sound-stage.

The spacey intro to L.A. Woman was served up beautifully by the M3x Vinyl, which makes the bass and drums intro even more exciting, with the excitement increased even more by how well the M3x Vinyl handled the crisp drumming of John Densmore. I think Densmore was pretty excited to be working with Scheff because I think he lifted his playing to a level higher than I’d ever heard from him before.

Listen particularly to the way his cymbals cut through the mix on this track: you won’t hear that using a lesser phono stage! Listen also to the repeated riff after the rhythm change at 3.02 and how the Musical Fidelity’s channel balance is so exact that you can hear the almost imperceptible difference in arrival times from left and right speakers. This is a level of detailing you just won’t hear from lesser phono stages.

On Crawling King Snake (a cover of a John Lee Hooker classic) you can hear not only the restraint of Marc Benno’s guitar contribution, but also the unrestrained scream of Robby Krieger’s lead. But then listen to how purely and delicately the M3x Vinyl delivers the final light-hearted Krieger contributions. The contrast is educational.

Morrison’s vocal on Riders on the Storm was also delivered marvellously well by the Musical Fidelity, and balanced perfectly against the ghostly background vocals. The sound of Manzarek’s Rhodes is also amazing, particularly in the upper octaves.

It’s a masterpiece of engineering, considering the ‘studio’ and the equipment used, so the album is a real tribute to the skills and talents of Bruce Botnick as well as those of the band. I can never really listen to the lyric of Riders on the Storm without thinking how it was a portent of Morrison’s death just three months later. The lyric also reflects that it was not only the last track on the album, but also the last track Morrison would ever release.

A real test for any phono cartridge – or any phono stage for that matter! – is the magical soundscape presented by the Alan Parsons Project’s album ‘I Robot’. I was absolutely captivated the minute the stylus dropped into the title track that kicks it off. The mezzo who sang the wordless lead vocal on this should have been given a credit. (Presumably it was Jaki Whitren, but it could also have been a member of the English Chorale).

The vocalise is a bit reminiscent of Pink Floyd’s Great Gig in the Sky (it’s actually much better!), which is rather fascinating when you consider that Parsons was the engineer for Dark Side of the Moon. The vividness of the orchestral colouring on this track was reproduced blindingly well by the Musical Fidelity M3x Vinyl.

I personally think this was Alan Parsons’ best album, mostly because it has more ‘best’ tracks than any other PP albums. those tracks being I Wouldn’t Want to be with You, Breakdown, and Some Other Time. I think his best-ever song is Eye in the Sky, but it and MammaGamma are the only good songs on his album of the same name (IMHO), so it misses out according to my personal criteria for ‘Best Album.’ (And yes, I know Alan Parsons Project is Alan Parsons and Eric Wolfson, so when I say one I mean both.)

The Parsons link dictated that ‘Dark Side of the Moon’ just had to be the next album on my auditioning list, and once again, the opening track dictated the auditioning mood because the clarity of the sound from the M3x Vinyl was such that as those fake ‘heart’ beats pulsed from the speakers, I could feel my body melting back into my listening chair.

Great sound has that ability to relax the soul, and the sound from the Musical Fidelity had me totally relaxed from the get-go. There’s an amazing amount going on in Speak to Me/Breathe, and I’m not only talking about the spoken contributions. Then in the following track, On the Run, listen to the pan that starts at 1.36 and then the panoply of effects that follows, and hear how the imaging ability of the M3xVinyl throws everything into stark relief. The breath sounds as the track closes out were rendered as well as I’ve ever heard them. Marvellous!

As for Time, I was revelling in the hollowness of the acoustic: the echoed percussion was rendered with amazing precision. Money revealed yet again the M3x Vinyl’s amazing ability to separate the left and right channels while still maintaining a crisp stereo image. And on Us and Them I snapped to attention when I heard the sound of Dick Parry’s sax – the M3x Vinyl was working wonders with it, so it was a flawless performance, both sonically and musically.

During every album that I played while I was preparing this review I experimented with the RIAA curve setting, switching back and forth between each and rather confoundingly, I found that I preferred the IEC-RIAA setting every time. I really wasn’t expecting this! And it wasn’t because it cut out rumble, because on all but one of the LPs I played there was no recorded rumble, and my system doesn’t have any rumble to remove anyway. The IEC-RIAA setting just sounded better to me, period.

As for that single LP I played that did have rumble on it (‘The Buskers’ Album’) the IEC-RIAA setting completely eliminated the rumble recorded on this album whilst leaving the street and traffic noises untouched. In other words, a perfect outcome.

Final verdict

Musical Fidelity’s M3x Vinyl phono stage is certainly a one-trick pony, in that it only does one thing and accommodates only one phono cartridge, but as Paul Simon says in his song of that name, “it turns that trick with pride”.

Full lab test results

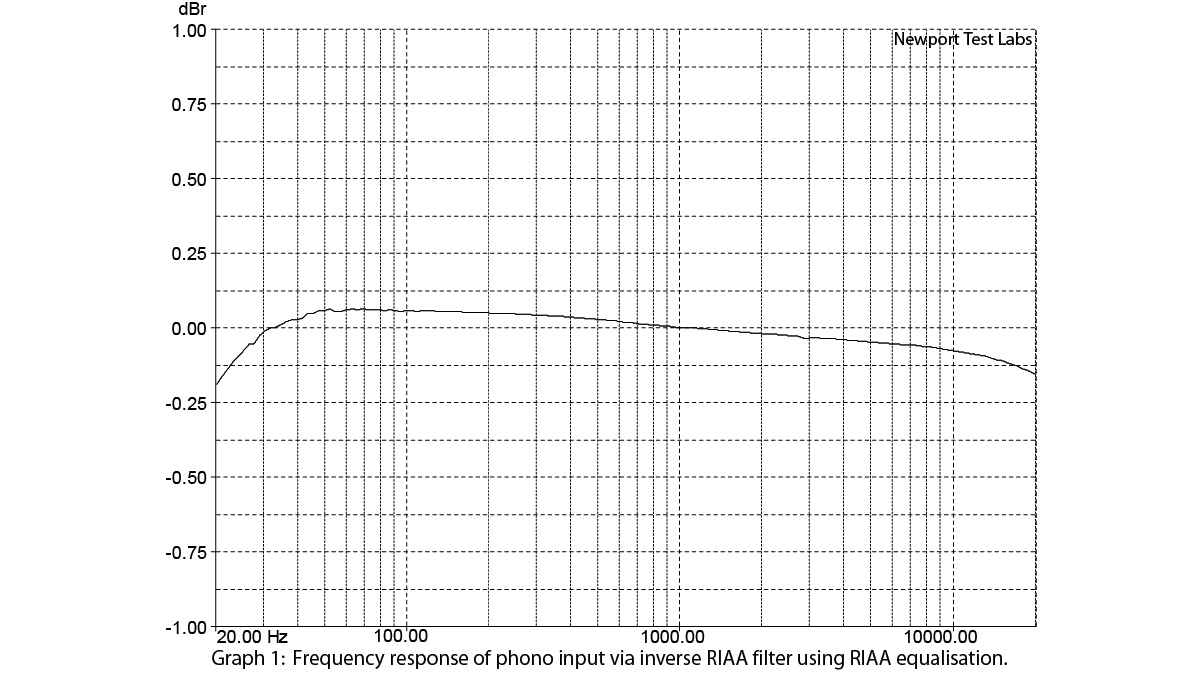

Newport Test Labs first measured the frequency response of the Musical Fidelity M3x Vinyl phono stage’s moving-magnet input using RIAA equalisation, the result of which is shown in Graph 1.

You can see that there’s a very slight ‘tilt’ to the overall response that would tend to emphasise the level of the lower frequencies and reduce the level of the very highest frequencies, but if you look at the vertical scale of this graph you’ll see that the top of it represents a +1dB increase and the bottom a 1dB decrease. This means that the response as shown is 20Hz to 20kHz ±0.13dB! This is not only outstandingly good, but also exceeds Musical Fidelity’s specification for it.

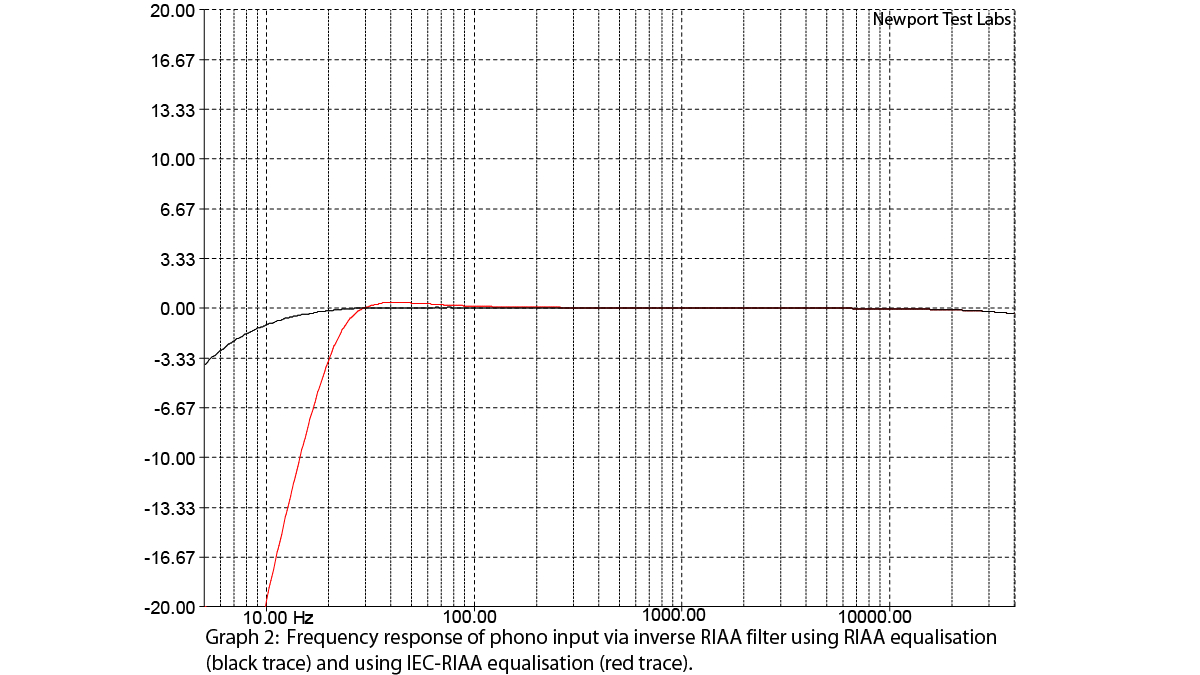

The frequency response of the moving-magnet stage using the Musical Fidelity M3x Vinyl’s IEC-RIAA equalisation setting is shown as the red trace in Graph 2, with the black trace showing the original RIAA response from Graph 1.

The vertical graph scale has had to be extended to accommodate the designed roll-off of the IEC curve, but you can see that the horizontal scale has also been extended down to 5Hz and out to 40kHz. With regard to the high-frequency extension, you can see that the M3x Vinyl’s response rolls off only very slightly from 20kHz, to be barely below reference at 40kHz. At the opposite end of the audio spectrum, the RIAA response is only 3.2dB down at 5Hz.

As for the low-frequency response of the IEC-RIAA equalisation, you can see that it’s only 3.33dB down at 18Hz yet is 20dB down at 10Hz, a very steep slope that’s actually 18dB/octave and will effectively reduce all unwanted noise, as the designers of this filter intended. The introduction of the filter means the frequency response is a little high between 30Hz and 100Hz but we’re only talking about a lift of mostly less than 1dB, so it’s not significant.

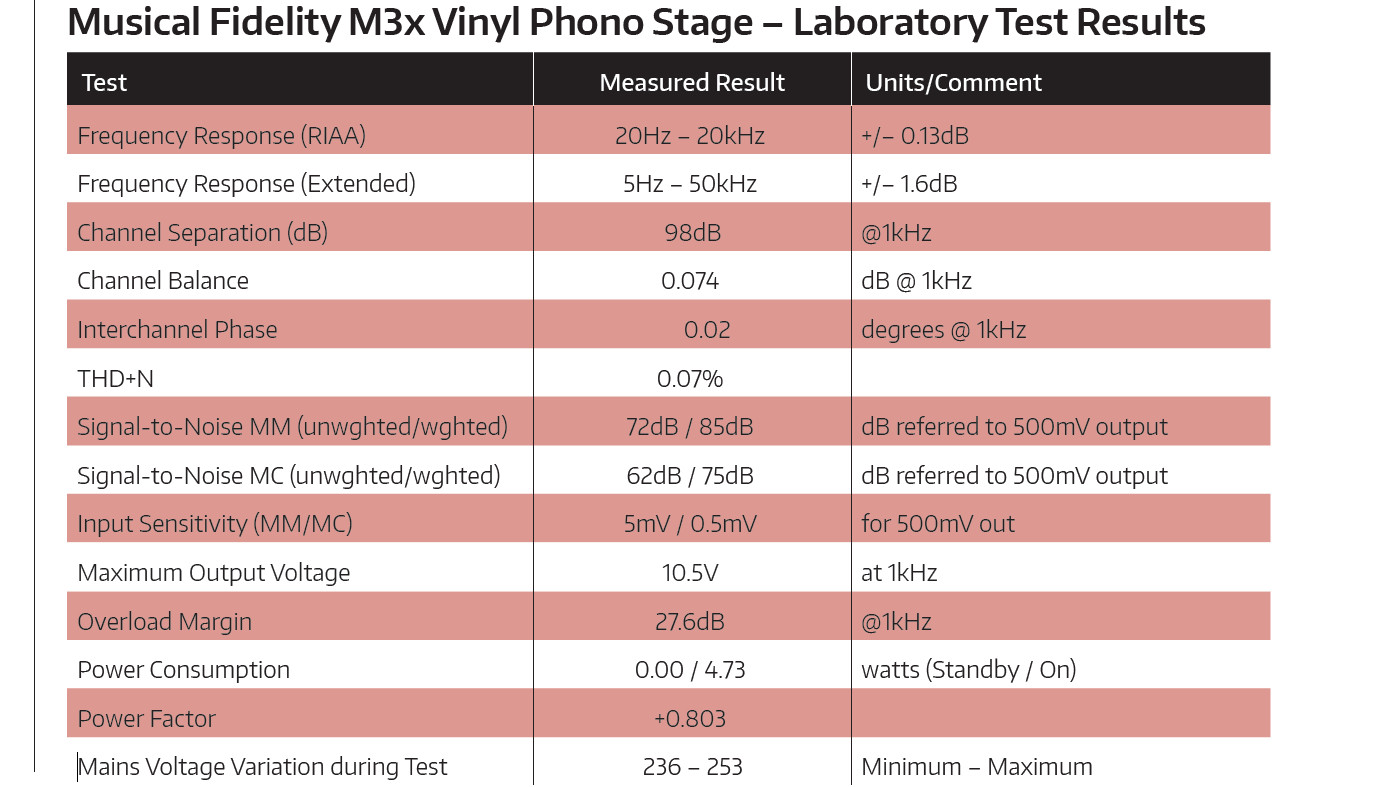

Channel separation was spectacularly good, with Newport Test Labs measuring it as 98dB at 1kHz. Channel balance at this same frequency was equally spectacular, at 0.074dB. Inter-channel phase was merely ‘very good’, at 0.02° at 1kHz.

All these figures are several orders of magnitude more than will ever be required to bring out the best in any phono cartridge, most of which, for example, have difficulty delivering channel separation of even 30dB at 1kHz and it usually diminishes to around 10dB at the frequency extremes. Likewise, few cartridges manage a channel balance of any better than 1dB between left and right channels, putting the M3x Vinyl’s 0.074dB result firmly into ‘overkill’ territory.

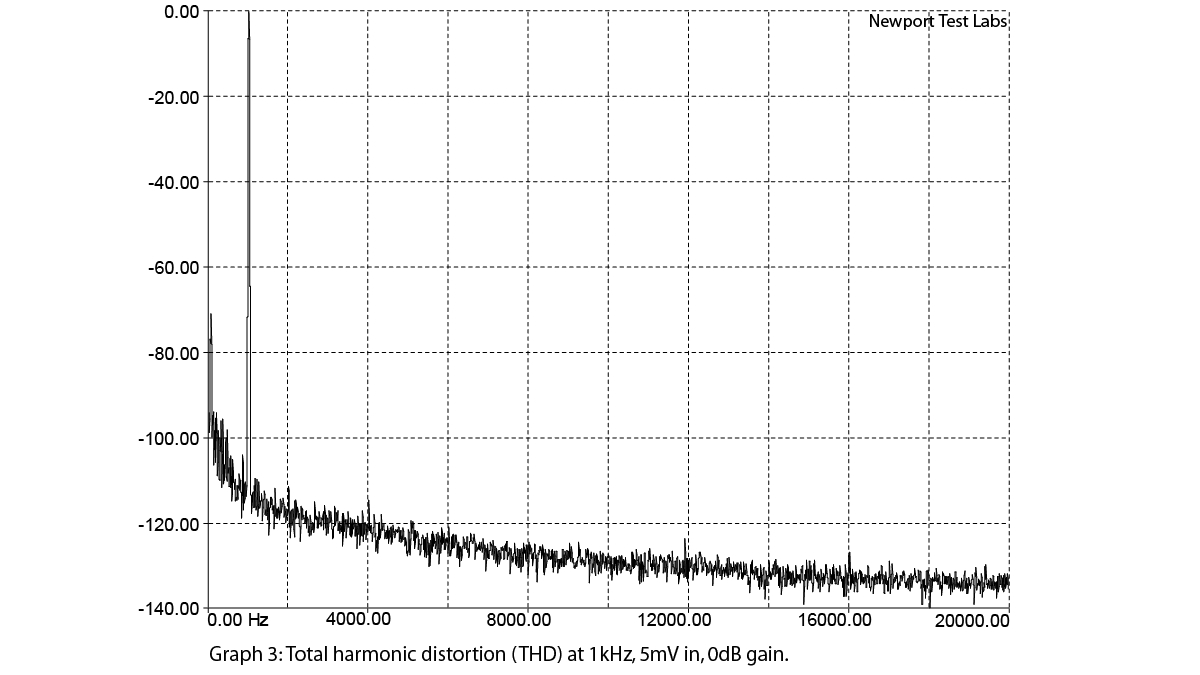

Graph 3 shows the Musical Fidelity M3xVinyl’s THD+N for a 5mV 1kHz test signal, with gain set for 0dB, which results in an output voltage of 500mV.

You can see there’s a tiny second harmonic distortion component at –112dB (0.00025%) and an even-tinier third harmonic component at –115dB (0.00017%). The noise floor is dominated by mains frequency noise (the peak visible at the extreme left of the graph, at around –72dB) but most of the circuit noise is more than 100dB down out to 4kHz, then more than 120dB down for higher frequencies. This is an exceptionally quiet phono stage.

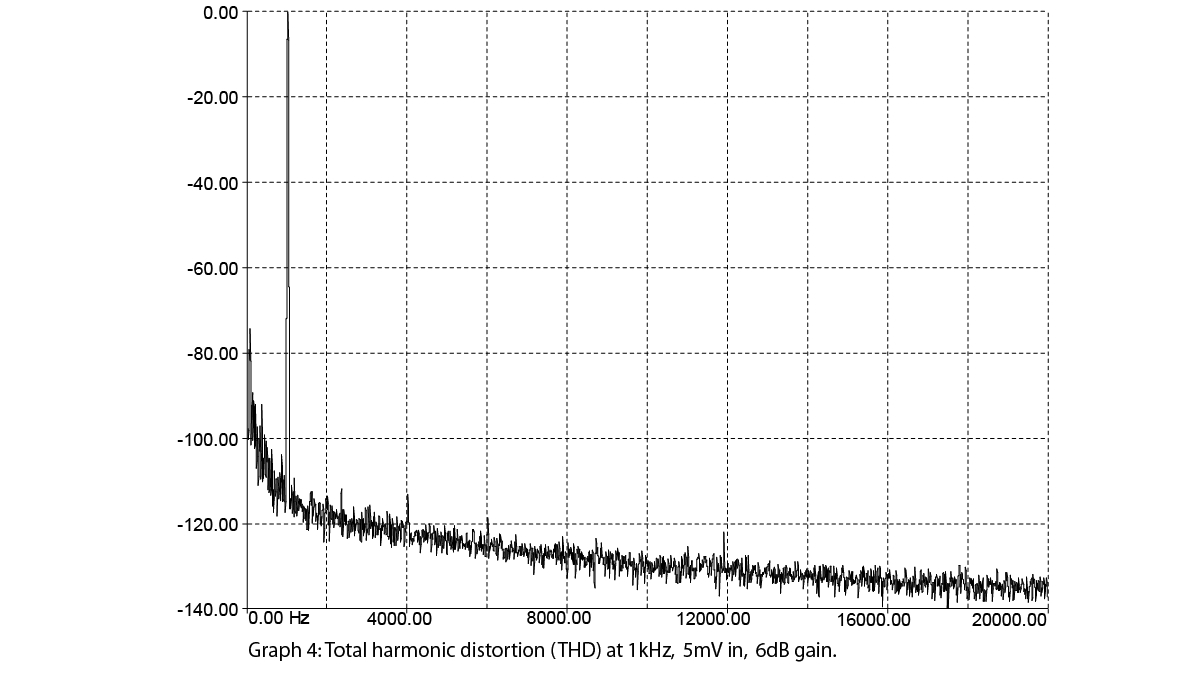

Graph 4 shows the result when Newport Test Labs input the same test signal but switched the M3x Vinyl to its +6dB gain setting. Mains noise has decreased a little, the second harmonic distortion has dropped below the noise floor which is at a level of –116dB at that frequency, and the 3rd harmonic remains at practically the same level it was for the 0dB gain setting.

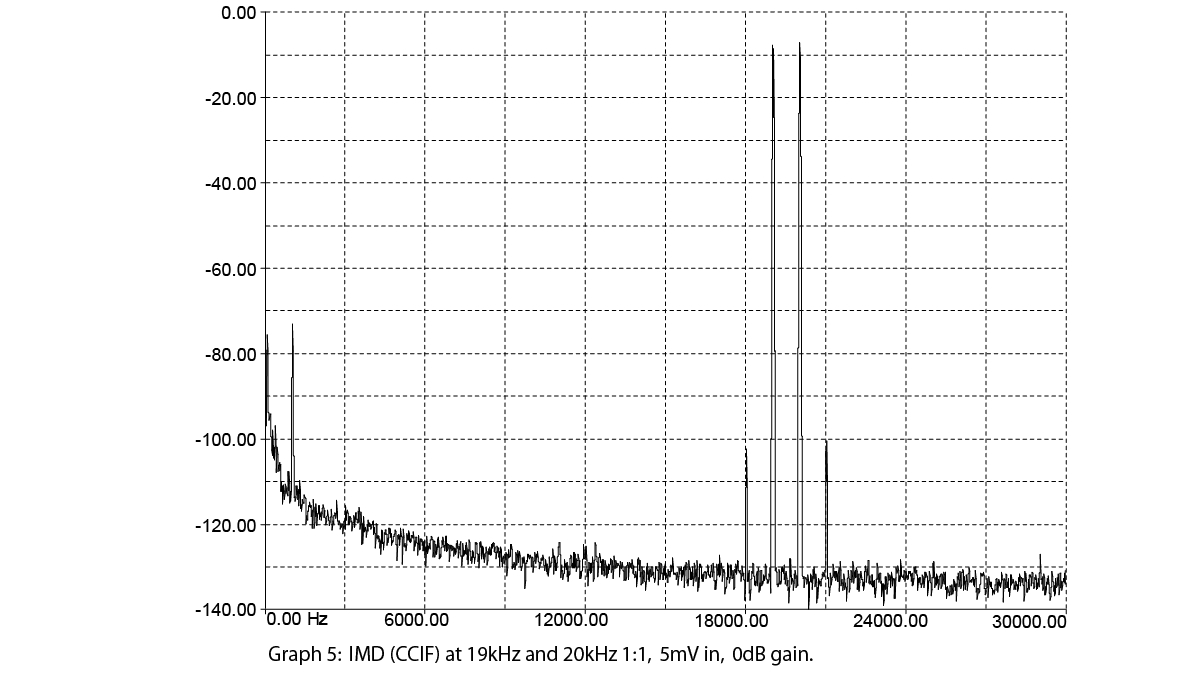

Graph 5 shows CCIF-IMD for 0dB gain. You can see there are sidebands either side of the two test signals, but they’re both more than 100dB down (0.001%). There is an unwanted difference signal generated down at 1kHz, sitting at around –73dB (0.02238%).

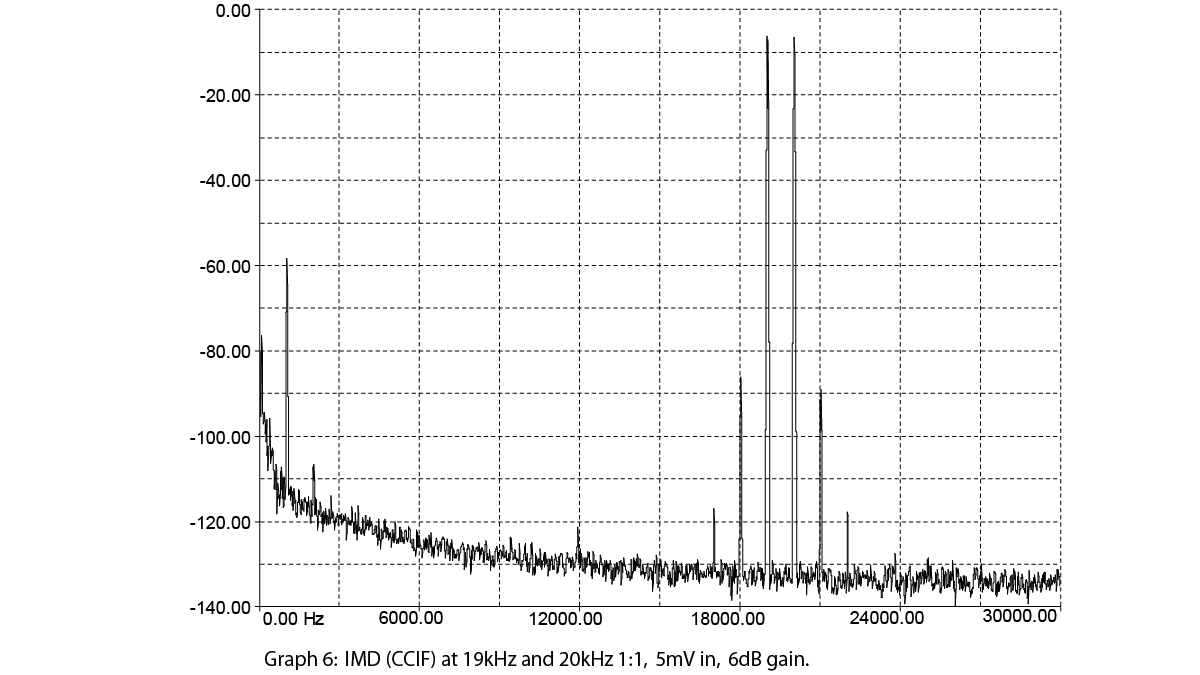

Graph 6 again shows CCIF-IMD, but this time with the M3xVinyl’s gain set to +6dB. This time, there’s more of a difference between the two gain settings, as you can see. The level of the 18kHz and 20kHz sidebands has increased to –86dB (0.00501%) and –89dB (0.00354%) respectively and there are two further sidebands at 17kHz and 21kHz, both of which are sitting down at around –117dB (0.00014%). The level of the 1kHz difference signal has increased to –58dB (0.12589%).

All the distortion results mentioned so far are excellent results, but if you were thinking that one or two might be a touch high, remember that even the very best phono cartridges produce second harmonic distortion levels of around –30dB (3.1%) and third harmonic levels of around –40dB (1.0%) so these would completely swamp any distortion introduced by the M3xVinyl. Overall THD+N for the Musical Fidelity M3x Vinyl was measured by Newport Test Labs at 0.07%, as shown in the tabulated test result chart below.

As you can see from the chart showing the results of the measurements made by Newport Test Labs, the M3x Vinyl’s signal-to-noise ratio was measured as 85dB A-weighted for a 500mV output for the moving-magnet input, and 75dB A-weighted for the same output level for the moving-coil input. These are both rather less than claimed by Musical Fidelity, which was likely referencing its specifications to a higher output level.

Input sensitivities and gain were exactly as per Musical Fidelity’s specification, with 5mV required in order to deliver 500mV at the output for the moving-magnet input, and 0.5mV for the same output voltage when using the moving-coil input when using the M3x Vinyl’s 0dB gain setting.

Newport Test Labs measured the Musical Fidelity M3x Vinyl’s maximum output voltage (before clipping) at 10.5 volts, slightly higher than claimed by Musical Fidelity.

Musical Fidelity’s M3xVinyl phono stage performed perfectly on Newport Test Labs’ test bench. It delivered superior results across all parameters that were measured, delivering performance far higher than will ever be required for any application for which it might be employed.

Australian Hi-Fi is one of What Hi-Fi?’s sister titles from Down Under and Australia’s longest-running and most successful hi-fi magazines, having been in continuous publication since 1969. Now edited by What Hi-Fi?'s Becky Roberts, every issue is packed with authoritative reviews of hi-fi equipment ranging from portables to state-of-the-art audiophile systems (and everything in between), information on new product launches, and ‘how-to’ articles to help you get the best quality sound for your home.

Click here for more information about Australian Hi-Fi, including links to buy individual digital editions and details on how best to subscribe.