5 things we learned watching Doctor Who with binaural audio

The fourth episode of Doctor Who's 10th series, titled 'Knock Knock', has been released on the BBC iPlayer with 3D audio. But what does that mean, and how can you experience it? We've got all the details.

In films and TV, the sound can make all the difference. The tension in a horror film's high-pitched scream, or the impact of a booming explosion, is nothing without detailed and punchy audio.

But when wearing headphones it's hard to feel like you're in the middle of the action - unless you use a binaural soundtrack which places sounds above, below, and around you, giving a greater sense of immersion.

That's exactly what the BBC has done with Knock Knock, the fourth episode of Doctor Who's 10th series. Set in a haunted house, where extraterrestrial insects that scurry inside the walls are this week's adversary for The Doctor and Bill, sounds come from every direction. This adds an extra level of realism to the show - or, at least, it does if you're watching via iPlayer.

We had an exclusive look at the technology behind this episode at its setting in Newport - this is what we found out.

It’s definitely immersive

So how does binaural recording actually work? Well, the answer is: exactly as normal hearing. The recordings are made for headphone use, and the microphones positioned to create a credible soundstage when using headphones (rather than when using a conventional pair of speakers).

Knock Knock's binaural mix means your ears are fooled into thinking the sound is coming from all around you, rather than just in a stereo format from your headphones. The creaks of floorboards come from underfoot, while the sound of scurrying in the attic truly seems like it's above your head.

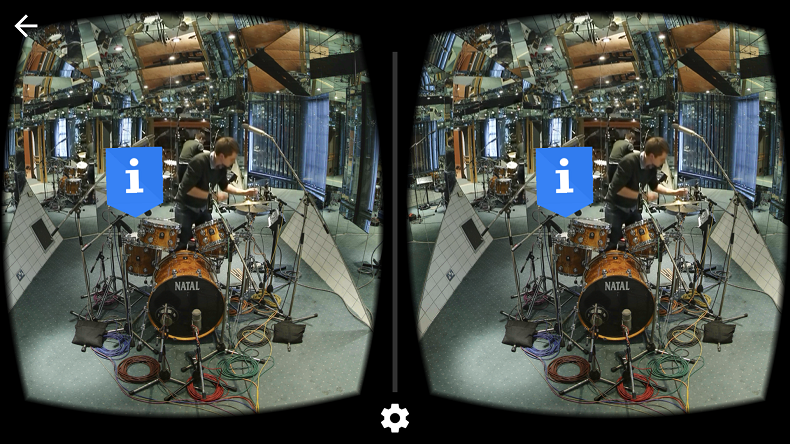

Of course, as the wise man once said, "Writing about music is like dancing about architecture" - so check out this video (while wearing headphones) for a taste of binaural audio, or watch the full 'binaural' episode online here.

The latest hi-fi, home cinema and tech news, reviews, buying advice and deals, direct to your inbox.

Binaural recordings have changed a lot

While it's not a cutting-edge technology - binaural demonstrations were first demonstrated in France in 1881, through the Théâtrophone - the way binaural recordings are made has changed with the advent of computers and algorithms.

In the early 1970s, dummy head microphones (like the one pictured above) were used. They had microphones in each ear cavity, so could account for extra variables like vibrations or reflection of sound off the shoulders external microphones wouldn't be able to pick up on.

However, these had a fair few practical issues: the dummies aren't easy to transport, and have to be placed in every location - and possibly moved for every new take - that the show is shot in.

For a programme like Doctor Who, which switches frequently between locations, this can be a challenge. Nowadays the BBC's sound-mixing team uses a piece of software called Nuendo to recreate the effect by artifically adding time delays and gain to a number of mono (single channel) recordings.

We’ll probably see more of it…but only in dramas

Binaural audio is something the BBC wants to do more often. But making a binaural mix, as well as the stereo and 5.1 surround mix for the standard and high-definition versions, takes more time than a normal recording.

For Knock Knock, adding a binaural soundtrack took approximately a week of work for the sound mixers - certainly not something you can do for every episode.

However, there are ways to cut the timescale down: one of these is by developing a sound format that can be decoded into stereo, 5.1 surround, and binaural depending on your output. By working in one format, rather than two, this could reduce the amount of time it takes to add a binaural mix from a week to as little as a day.

That said, you still won't hear binaural audio on every type of show. Right now, it will focus on dramas (or, more specifically, programmes with foreign markets).

This is because having dialogue over a sound effect makes it more difficult to mix binaurally, but drama programmes often have their audio effects recorded separately, so other countries can place dialogue in their native languages over the top. This means the sound engineer has a cleaner sound to manage.

You have to account for people having bad headphones

While it's very easy to play a binaural recording in your home or from your phone - all you need is a pair of headphones - not everyone places the same degree of importance to sound quality as What Hi-Fi? readers undoubtedly do.

As much as we'd love everyone to use the best headphones they can afford, a good number of people stick to the pair bundled with their smartphone.

This means the BBC's sound mixers, who usually edit using £100 Beyerdynamic DT100 headphones, need to make adjustments to ensure people using £10 headphones don't lose out.

For example, LFE (low frequency effects) need to be moved a little higher into the frequency range to account for headphones that won't be able to pick up on the low bass. Similarly, those expecting high levels of tension from an insightful treble might be a little disappointed if they're not using suitably sophisticated pair of cans.

The dynamic range is also compressed a little more, so that people using smartphones don't need to have the volume turned up to potentially damaging degrees. Ultimately, the more people using better headphones, the better quality we'll get from binaural sound.

It’s the perfect partner for VR television

Of course, while binaural audio might reach more people through the BBC iPlayer, it really makes waves when used with virtual reality.

The Beeb has utilised this tech before, as with Google Daydream projects like Turning Forest, but the number of people using VR products (such as Oculus Rift or Samsung Gear VR) is still pretty small.

It might grow when more streaming services, such as Netflix, take steps towards VR programming, but right now its efforts are lacklustre.

We might also be able to get binaural audio without wearing headphones, using head-tracking software to monitor a listener's movements, but progress is slow - slower when working on the possibility of multiple people in one room. Right now, the closest thing you'll get to immersive audio without headphones is still Dolby Atmos.

Adam was a staff writer for What Hi-Fi?, reviewing consumer gadgets for online and print publication, as well as researching and producing features and advice pieces on new technology in the hi-fi industry. He has since worked for PC Mag as a contributing editor and is now a science and technology reporter for The Independent.