Devialet and the art of impermanence

As part of the 'Lost Recordings' initiative, Devialet and Fondamenta treated a Royal Albert Hall audience to playback of a lacquer pressing of jazz singer Sarah Vaughan. How did they make it happen?

The latest hi-fi, home cinema and tech news, reviews, buying advice and deals, direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

For some people, the best thing about a live performance is its impermanence - knowing what you’re hearing will be lost to the ages once it's finished. For others, that exact quality is a tragedy - they hope for a recording good enough to hear again some semblance of the event.

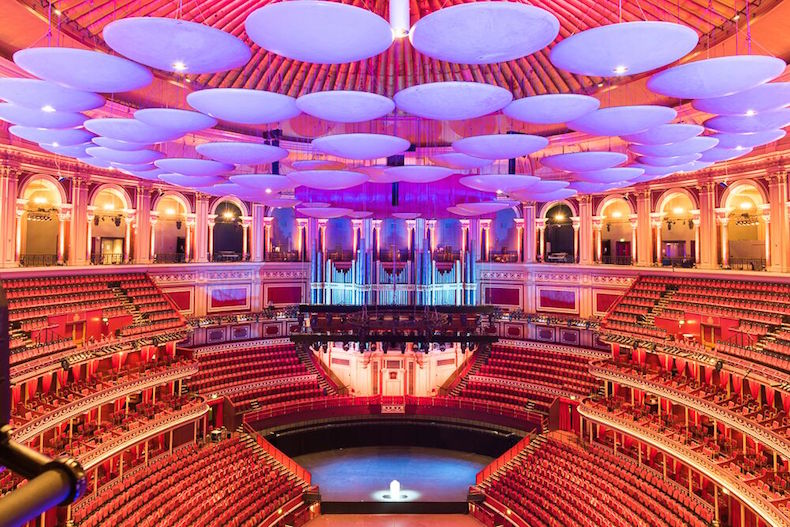

At the Royal Albert Hall in London’s Kensington, hi-fi manufacturer Devialet and the record label Fondamenta put on a demonstration of their remastering abilities. The event turned on the playing of a previously unreleased recording of jazz singer Sarah Vaughan at the Laren Jazz Festival in 1975 through two £110,000 Focal Grande Utopia EM speakers (which we saw at the Munich High End show) and a £30,000 Kronos turntable.

MORE: Devialet Gold Phantom review

Article continues belowThe record was found by retired sound archeologist M. Piet Tullenaar, who worked in audio archives for almost 40 years. Vaughan’s recording is the third of three performances remastered in this way, following Oscar Peterson's performance at Concertgebouw in 1961, and Bill Evans at Hilversum in 1968.

Each one comes from different vaults in the Netherlands - Vaughan’s performance comes from one of the studios of Beel en Geluid, the Netherlands Institute for Sound and Vision - but the two companies are looking to open more vaults in other countries as part of the 'Lost Recordings' project. Their mission is to find rare or unreleased recordings and use Fondamenta’s 'Phoenix Mastering' process to bring them up to a the quality of today’s vinyl.

'Phoenix Mastering' sounds impressive (if a little like something you might find on the Hogwarts curriculum), but what actually is it? We spoke to Fondamenta’s founder Frédéric D'Oria-Nicolas, and he told us the process is broken down into four stages.

MORE: The tech behind the big vinyl revival

The latest hi-fi, home cinema and tech news, reviews, buying advice and deals, direct to your inbox.

The first is preparing the physical sources - whether they’re magnetic tape, vinyl records or 78rpm shellac gramophone records - by using heating techniques and ultrasound cleaning. The sources are then read and converted using the A-to-D converter in Devialet’s Expert Pro amplifier, which D'Oria-Nicolas says is the best possible way of digitally converting the signal.

Once the signal is digitised, it’s treated using processing algorithms to try and reduce residual noise - a process that isn’t always easy. While the tapes were in good condition, the Peterson performance proved the most difficult. The tapes hadn't been opened since 1962, and had much more analog noise than the others.

D'Oria-Nicolas also told us how, in the Evans’ recording, “the drums were too close to the piano and some frequencies did make some drum skins vibrate… We successfully managed to delete that.”

“Of course, we can talk of all the little details of restoring, but the whole challenge is the whole impression of dynamics, of soundstage, of tones’ truth.”

MORE: How does a vinyl record make a sound?

Once the recording has been digitised it’s pressed into an 180gm record, of which 900 are made of each artist. But for those looking for even higher quality and rarity, Devialet is also releasing 30 sets of four lacquers for the Vaughan and Peterson recordings (for £6300), and two lacquers of the Evans recording (at £4500).

Usually when a record is made, the lacquers are used for production rather than for listening because its softness means the grooves are worn off as it’s played. Which adds that fleeting quality that makes it, philosophically speaking, as similar as a recording can be to a live performance.

D'Oria-Nicolas also takes quite a philosophical outlook on it, saying that he feels it’s “poetic to press some lost recordings on an medium of their own time … we have filled a gap in time by replacing the missing piece”.

And we can safely say that history has never sounded so good.

READ: All our Devialet reviews

What Hi-Fi?, founded in 1976, is the world's leading independent guide to buying and owning hi-fi and home entertainment products. Our comprehensive tests help you buy the very best for your money, with our advice sections giving you step-by-step information on how to get even more from your music and movies. Everything is tested by our dedicated team of in-house reviewers in our custom-built test rooms in London, Reading and Bath. Our coveted five-star rating and Awards are recognised all over the world as the ultimate seal of approval, so you can buy with absolute confidence.